News

COMMEMORATING 30 YEARS OF TFF

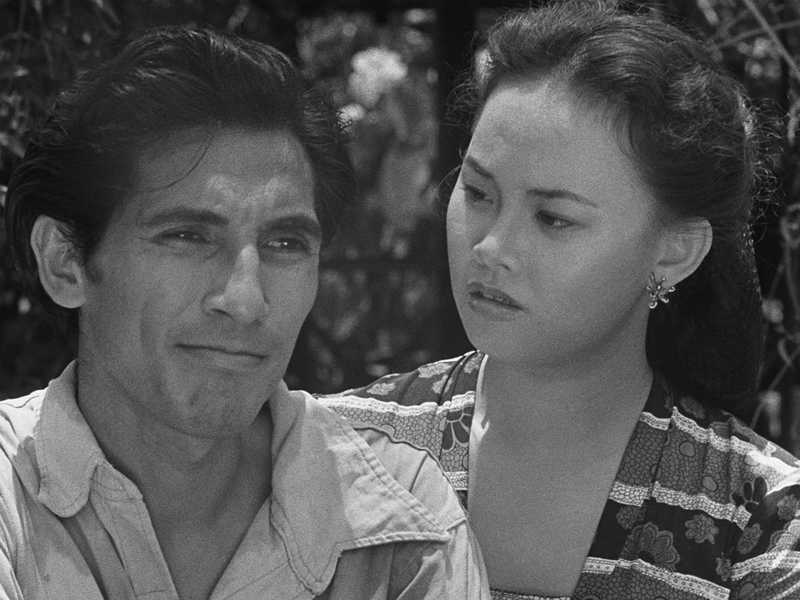

William Wellman directed just short of 80 movies between 1923 and 1958, of all kinds. Some are renowned classics. Some are genuinely terrible. Some are ambitious and some are lightweight entertainments. And many of his films—like most of his astonishing pre-code output at Warner Brothers (17 movies in three years)—are bursts of pure cinematic energy. The Film Foundation has helped to restore three of Wellman’s films, with the Academy, the AFI, UCLA and the George Eastman Museum. Beggars of Life, a late silent and partial talkie (the sound sequences are lost) made at Paramount in 1928, throbs with the energy between Richard Arlen and Louise Brooks. The scene where they meet for the first time is a wonder. Brooks is a farm girl who has just murdered her abusive stepfather in self-defense. Arlen, a hobo, wanders into the house in search of food, sizes up the situation and immediately understands that she needs a protector, and they take to the road together. The freshness and pure beauty of their presences, the wordless exchange of emotions, the sudden shift into action and flight, make for one of the most beautiful entries into a movie that I know, and their physical and emotional journey—they meet up with a pack of potentially dangerous hobos led by Wallace Beery—is rough and vivid and lyrical. There is a real kinship with certain Jean Renoir films from the 30s, Toni and The Lower Depths in particular, albeit in a bright, brash American key. It’s interesting to note that both Wellman and Renoir were flyers in the First World War.

In the 40s, Wellman made one of the very few films about war that really feels like it was made by someone who went to war. The Story of G.I. Joe, based on the frontline dispatches of war correspondent Ernie Pyle, portrays the camaraderie and above all the fatigue of war so beautifully and eloquently. Like Beggars of Life, but in a far more sombre key, it pulses with life. And it brings to mind a point that many people have made over the years about the directors who began in the silent era, and that I think bears repeating. In 1978, Scott Eyman interviewed Wellman, and he asked him about how one learns to become a movie director. Wellman gives him an answer that’s as true in its aim as one of his best movies: “You have to learn how to live before you learn how to direct.”

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

BEGGARS OF LIFE (1928, d. William Wellman)

Restored by the George Eastman Museum with funding provided by The Film Foundation.

THE STORY OF G.I. JOE (1945, d. William Wellman)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and The Film Foundation.

Out of the Vaults: The Man with the Golden Arm (1955)

Meher Tatna

When director Otto Preminger bought the rights to make The Man with the Golden Arm, he knew he would have problems with the Production Code Administration: he knew they would refuse to grant him a Code seal to release the movie. The film dealt with drug abuse, a subject that was censored, along with miscegenation, prostitution, abortion, and words like “virgin” and “pregnant.” Undeterred, Preminger started production on the picture, vowing to release it without the seal if he had to. United Artists, the studio backing the film with a million-dollar investment, was behind him, despite the certainty of a $25,000 fine from the MPAA, and despite the fact that Preminger had given it an out if the seal was denied. UA resigned from the MPAA (it rejoined later) and released the film through the many cinemas that were willing to book it. Following the controversy that ensued, there was an investigation of the PCA’s Code approval process, and the 25-year-old Code was overhauled for the first time since its adoption in 1930.

The Man with the Golden Arm finally received a seal in 1961 and Preminger, to whom the rights had reverted, sold the television rights to ABC, who were contractually bound not to cut the film. Preminger even got to decide where the commercial breaks would be inserted.

The film was based on Nelson Algren’s 1949 bestselling book of the same name, the first to win a National Book Award. Algren sold the film rights to UA, was hired and then fired as the film’s screenwriter, and later disavowed the film, saying that it bore little resemblance to the story he wrote.

In the film, Frank Sinatra plays Frankie Machine, a poker dealer (the man with the golden arm), who has just been released from prison. He has kicked his drug habit thanks to the prison doctors and now wants to give up gambling and become a musician. He returns to his life in Chicago and to his wife Zosh (Eleanor Parker, borrowed from MGM), a malingering invalid in a wheelchair who wants things to go back the way they were, and repeatedly thwarts his dream of playing in a band. Slowly, Frankie finds himself sucked into his old bad habits, despite the best efforts of his girlfriend, played by Kim Novak, borrowed from Columbia. (Columbia was paid $100,000 for her; she made $1,000 a week.) Robert Strauss plays Schweifka, the poker boss who lures Frankie back with the promise of money for his sick wife; Darren McGavin plays his ruthless pusher Louie.

Sinatra turns in a fine performance as the addicted Frankie; his natural charm makes a weak character seem sympathetic as he struggles through his recidivism and his eventual attempt to “kick the monkey.” The star spent time at drug rehabilitation facilities studying inmates in order to inform his performance. Most of the cast is equally strong, particularly McGavin as Louie – he’s seen it all in his jaded life, and he knows before Frankie does, that all it will take is the offer of a free fix for Frankie to fall. Equally good is Arnold Stang as the dimwitted sneak thief Sparrow, faithful to his friend Frankie until Frankie has no time for him anymore. The one performance that is below par is that of Parker, playing Zosh in a hyper, borderline hysterical way, indicating her character rather than performing in a truthful way.

Preminger was widely known as a bullying director, hectoring his actors and routinely humiliating them, famous for quotes like “I do not welcome advice from actors, they are here to act,” and “Marilyn Monroe? A vacuum with nipples.” However, he did guide nine actors (including Sinatra) to Oscar-nominated performances and had a successful career in Hollywood despite his difficult reputation.

When both Sinatra and Brando were offered the role of Frankie, Sinatra swooped in and commandeered it, smarting from the fact that he had lost On the Waterfront to his rival. His instincts were right, and he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor. The film also got nominations for art direction for Joseph C. Wright and Darrell Silvera, and for the score for Elmer Bernstein.

The distinctive crooked arm on the poster and publicity materials for the movie, designed by Saul Bass, is considered a tour de force of movie marketing and was listed by Premiere magazine as one of ‘The 25 Best Movie Posters Ever. In the paper-cut animation on the title credits, white bars appear and disappear against a black background accompanied by Bernstein’s score, ending with the same disjointed hand, meant to convey the grimness of the subject with the lightest of touches.

The jazz score, composed by then 33-year-old Elmer Bernstein, is another triumph. Bernstein hired drummer Shelly Manne, Shorty Rogers and Pete Candoli on trumpets, Milt Bernhart on trombone and Bud Shank on alto saxophone, all musician virtuosos to do the solos: he had been given three weeks to compose the score, and never saw the opening credits ahead of time as Bass was working on them simultaneously. “The intent of this opening was to create a mood spare, gaunt, with a driving intensity… [to convey] the distortion and jaggedness, the disconnectedness and disjointedness of the addict’s life the subject of the film,” Bass said at the time, and Bernstein, with his drums, horn, and trumpet, reflects the feeling musically in the accompanying cut Clarke Street as the credits end and Frankie steps off the bus into his life on that street. (It was Manne who taught Sinatra to play drums in the movie.)

“(Themes from) The Man with the Golden Arm” reached No. 14 on the Billboard chart in 1956, written by Bernstein and performed by Richard Maltby and His Orchestra.

The film diverges from the book in many ways. In the book, Frankie is a morphine addict; in the film, the drug is never named, but it’s obviously heroin: in the one scene where Frankie’s pusher, Louie, administers the drug to him, although the scene was cut down to the bare minimum to appease the PCA, the method is that used as for injecting heroin. The way Louie meets his end in the film is different from that of the book. Finally, the bittersweet way in which the movie ends is very different from the grim ending of the book, in which Frankie commits suicide. Reviewers of the film were kind, though a lot of critics took exception to the ending, calling it contrived, but the film was a financial success despite them. At the end of a long series of court battles, The Man with the Golden Arm was widely released throughout the world, probably because of the publicity it garnered, and earned $4.3 million.

The master was stored in a rented film vault in New Jersey, where intense rainstorms and flooding caused several film elements to be damaged beyond repair. Some of these film elements included the original camera negative and optical track negative. Although the original elements were destroyed, two fine-grain master positives, both with soundtracks, survived and were brought to the Academy Film Archive for inspection and restoration. A new dupe negative and track negative was made at the YCM Laboratory. DJ Audio performed the audio transfers and Audio Mechanics completed the digital audio restoration. It was restored by the Academy Film Archive with funding from The Film Foundation and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. The film is in the public domain.

Immerse Yourself in Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project #3

Brian Tellerico

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project began in 2007, with a commitment to restoring and releasing films from parts of the world where filmmaking was difficult for political and cultural reasons. While some of these restorations resulted in films or at least works by filmmakers who had been recognized, some never would have found their way to a modern audience without WCP. As streaming service gatekeepers seem to be reducing the chances for people to see international cinema more than enabling it—yes, the Criterion Channel has a healthy foreign selection, and so does Kanopy and Mubi, but the “major” streamers like Netflix and Hulu are depressingly thin—releases like Criterion’s “World Cinema Project #3” feel more and more like a gift. Six films restored by the WCP are included in this multi-disc set from Criterion, including two films per Blu-ray and single DVDs for each title. Each release is accompanied by an informative introduction by Martin Scorsese, briefly detailing the history of the film, and one only wishes they were longer than two minutes. But Scorsese doesn’t want to draw focus here, and he allows this diverse, international array of cinema to speak for itself.

Take “After the Curfew,” recognized as the first Indonesian film ever made. Released in 1954, the movie by Usmar Ismail spoke to the history of its country, telling the story of a former freedom fighter who can’t readjust to civilian life after the revolution that granted Indonesia independence from the Netherlands. This film really exemplifies the overall purpose of the World Cinema Project in so many ways. For one, it is deeply specific to its time and place, telling a story of postcolonialism in Indonesia in way that an outsider never could. It has a cultural specificity that feels essential to the films that WCP and Criterion chooses for these releases. But it is also not merely a historical document. Ismail’s use of light and shadow doesn’t reflect a culture crawling before it can walk in cinematic terms as much as a director who clearly watched works from around the world to adapt their visual language to his own purposes. It’s a fascinating piece of work.

So is the formally breathtaking “Lucia,” a Cuban film from 1968 that runs nearly three hours, telling a triptych story of three women named Lucia across three distinct time periods in the history of the country. Director Humberto Solás tackles the tumultuous history of his people by dropping viewers into 1895, 1932, and the 1960s, detailing how much progress comes through pain and often at the cost of humanity. It is a visually stunning movie—each section has a different visual language—and sometimes shockingly surreal, playing out unlike anything Criterion has released in a long time. That’s another benefit of these releases—they pull a collection that’s often defined by white, European filmmakers to other parts of the world.

Héctor Babenco is probably the best known of the filmmakers in this set, as the Argentinian filmmaker would go on to direct “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” “Ironweed,” and “At Play in the Fields of the Lord.” Even the film included here in the set received the widest international release of the six, 1980’s "Pixote,” a film that Roger Ebert considered a Great Movie, writing, “"Pixote" stands alone in his work, a rough, unblinking look at lives no human being should be required to lead. And the eyes of Fernando Ramos da Silva, his doomed young actor, regard us from the screen not in hurt, not in accusation, not in regret—but simply in acceptance of a desolate daily reality.

If Babenco’s film is well-known when compared to other films in the WCP, its Blu-ray disc-mate is the opposite. Even Scorsese himself, one of the smartest people alive when it comes to world cinema, admits he hadn’t seen or considered Juan Bustillo Oro’s “Dos Monjes” before this project started, but the WCP went to historians around the world asking for suggestions. Oro's movie is something else, one of the first Mexican sound films, and a melodrama that draws heavily from the German Expressionism movement while also echoing Universal monster movies being made around the same time. Released in 1934, it’s the story of a new monk at a cloister who is recognized and despised by one of the brothers there. The film then shifts to two flashbacks of the same story, long before “Rashomon,” to tell the story of their shared past. It’s a visually striking, surreal experience, and maybe my favorite film in this set.

Finally, “Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project #3” travels to the incredibly distinct cultures of Mauritania and Iran for the last disc in this set. Med Hondo’s “Soleil Ô” was released in 1970 and reflects its Mauritanian director’s culture and politics at the time through the story of an immigrant who travels from West Africa to Paris trying to find work, but only finding aggression. And then there’s Bahram Beyzai’s “Downpour,” a 1972 work credited with helping start the Iranian New Wave. Restored from the only surviving print, it’s another example of how the World Cinema Project isn’t just bringing films to people who might not otherwise have a chance to see them but actually rescuing and salvaging cinema from around the world. May they never stop.

Get your copy of “Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project #3” here. Note: some of these films are also available on the Criterion Channel.

COMMEMORATING 30 YEARS OF TFF

For decades now, there has been a stream of citations and lengthy magazine articles on the topical relevance of A Face in the Crowd, Elia Kazan and Budd Schulberg’s 1957 follow-up to On the Waterfront. I can’t recall a moment in the last 30 years that this film, about the meteoric media-fueled rise of a folksy southern guitar-playing “personality” named Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith in his film debut), hasn’t been deemed “prescient.” The crux of the matter is the clear link that Kazan and Schulberg drew between commercially driven mass media popularity and political power, five years before Daniel Boorstin’s book The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America, 7 years before Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media and 11 years before Joe McGinnis’s The Selling of the President. In 1976, when Ronald Reagan took his first shot at the presidency, public perception hadn’t quite caught up: the idea of a former movie star turned commander-in-chief still seemed borderline outlandish to many people. After 1980, there were calls for Gregory Peck to run for president (a role he wound up playing in a crazy mid-80s film called Amazing Grace and Chuck). Now, we all have the language of “imaging,” “branding,” “messaging,” “talking points” and “online communities” shoved at us at all times from multiple directions. Many people seem to be caught between embracing the figures that are the savviest at manipulating the tools of image promotion and the ones who appear to cut through it all and speak directly.

Under the current circumstances, A Face in the Crowd, restored by UCLA in collaboration with The Film Foundation, still seems prescient. But now, it’s the terrible sadness of megalomania that resonates, the bottomless longing for love, validation and acclimation. I look forward to the moment when this film is no longer politically relevant. And what has always burned most brightly is the element that Kazan prized the most: the relationship between Patricia Neal and Andy Griffith. Because at its core, A Face in the Crowd is the story of a woman who is drawn to and soon betrayed and finally horrified by her own creation.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

A FACE IN THE CROWD (1957, d. Elia Kazan)

Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive in cooperation with Castle Hill Productions, Inc. with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and The Film Foundation.

ON THE WATERFRONT (1954, d. Elia Kazan)

Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art with finding provided by The Film Foundation.