Martin Scorsese created the World Cinema Project (WCP) in 2007 recognizing the urgent need to preserve, restore, and provide access to films from around the world. To date, 70 films from Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America, South America, and the Middle East have been restored, preserved, and exhibited for global audiences. As part of the WCP, the African Film Heritage Project (AFHP) was launched in 2017 in partnership with the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (FEPACI) and UNESCO, in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna, to preserve the legacy of African cinema. The WCP also supports Restoration Film Schools, intensive, results-oriented workshops allowing students and professionals to learn the art and science of film restoration and preservation. Titles are available for exhibition rental by clicking "Book This Film."

AFTER THE CURFEW

LEWAT DJAM MALAM

Director: Usmar Ismail

WRITTEN BY: Usmar Ismail, Asrul Sani

EDITING: Sumardjono

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Max Tera

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: G.R.W. Sinsu

SOUND: B. Saltzmann

FROM: Sinematek Indonesia

PRODUCTION DESIGN: Persari, Perfini

STARRING: A.N. Alcaff (Iskandar), Netty Herawaty (Norma), R.D. Ismail (Gunawan)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Indonesia

LANGUAGE: Indonesian

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 101

SET DESIGNER: Abdul Chalid

Restored in 2012 by the National Museum of Singapore and Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, Konfiden Foundation, Kineforum of the Jakarta Arts Council, and the family of Usmar Ismail Estate. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

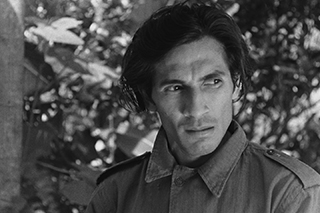

Lewat Djam Malam (After the Curfew) is a passionate work looking directly at a crucial moment of conflict in Indonesian history: the aftermath of the four-year Republican revolution which brought an end to Dutch rule. This is a visually and dramatically potent film about anger and disillusionment, about the dream of a new society cheapened and misshapen by government repression on the one hand and bourgeois complacency on the other.

The film’s director, Usmar Ismail, is generally considered to be the father of Indonesian cinema, and his entire body of work was directly engaged with ongoing evolution of Indonesian society. He began as a playwright and founder of Maya, a drama collective that began during the years of Japanese occupation. And it was during this period when Ismail developed an interest in filmmaking. He began making films for Andjar Asmara in the late 40s and then started Perfini (Perusahaan Film Nasional Indonesian) in 1950, which he considered his real beginning as a filmmaker. Lewat Djam Malam, a co-production between Perfini and Djamaluddin Malik’s company Persari, was perhaps Ismail’s greatest critical and commercial success.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Lewat Djam Malam has been digitally restored using the original 35mm camera & sound negatives, interpositive, and positive prints preserved at the Sinematek Indonesia. The original camera negative was scanned at 4K resolution.

The digital restoration began by focusing on fixing instability and flicker followed by the meticulous work of dirt removal, carried out both by automatic tools and by a long manual process of digitally cleaning each image (frame by frame). The film also suffered from signs of mould and vinegar syndrome –the laboratory took great pains to address these problems without damaging the definition of the photographic output, specifically with regards to details and faces.

The original sound was digitally restored using the 35 mm original soundtrack negative. Two reels were missing from the soundtrack negative, and were therefore taken from the combined interpositive. The last 2 minutes of reel 5 were missing from all available elements, but were recovered from a positive copy. The soundtrack has been scanned using laser technology at 2K definition. The core of the digital sound restoration consists on several phases of manual editing, high resolution de-clicker & de-crackle, and multiple layers of fully automated noise reduction.

The restoration was completed at L’immagine Ritrovata laboratory on March 2012.

Image: © Courtesy of the Usmar Estate

AL MOMIA

NIGHT OF COUNTING THE YEARS, THE

Director: Shadi Abdel Salam

WRITTEN BY: Shadi Abdel Salam

EDITING: Kamal Abou El Ella

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Abdel Aziz Fahmi

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Mario Nascimbene

FROM: Egyptian Film Centre

STARRING: Ahmed Marei (Wannis), Ahmed Hegazi (Brother), Zouzou Hamdi El Hakim (Mother), Nadia Lofti (Zeena)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Egypt

LANGUAGE: Arabic with French and English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 103 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Egyptian General Cinema Organization

SET DESIGNER: Salah Marei

Restored in 2009 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, and the Egyptian Film Center. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways, Qatar Museum Authority and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

Momia, which is commonly and rightfully acknowledged as one of the greatest Egyptian films ever made, is based on a true story: in 1881, precious objects from the Tanite dynasty started turning up for sale, and it was discovered that the Horabat tribe had been secretly raiding the tombs of the Pharaohs in Thebes. A rich theme, and an astonishing piece of cinema. The picture was extremely difficult to see from the 70s onward. I managed to screen a 16mm print which, like all the prints I’ve seen since, had gone magenta. Yet I still found it an entrancing and oddly moving experience, as did many others. I remember that Michael Powell was a great admirer. Momia has an extremely unusual tone – stately, poetic, with a powerful grasp of time and the sadness it carries. The carefully measured pace, the almost ceremonial movement of the camera, the desolate settings, the classical Arabic spoken on the soundtrack, the unsettling score by the great Italian composer Mario Nascimbene – they all work in perfect harmony and contribute to the feeling of fateful inevitability. Past and present, desecration and veneration, the urge to conquer death and the acceptance that we, and all we know, will turn to dust… a seemingly massive theme that the director, Shadi Abdel Salam, somehow manages to address, even emobody with his images. Are we obliged to plunder our heritage and everything our ancestors have held sacred in order to sustain ourselves for the present and the future? What exactly is our debt to the past? The picture has a sense of history like no other, and it’s not at all surprising that Roberto Rossellini agreed to lend his name to the project after reading the script. And in the end, the film is strangely, even hauntingly consoling – the eternal burial, the final understanding of who and what we are… am very excited that Shadi Abdel Salam’s masterpiece has been restored to original splendor.

–Martin Scorsese, May 2009

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Al Momia used the original 35mm camera and sound negatives preserved at the Egyptian Film Center in Giza. The digital restoration produced a new 35mm internegative. The film was restored with the support the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

Image: © Courtesy of Egyptian Film Centre

ALYAM, ALYAM

Director: Ahmed El Maanouni

WRITTEN BY: Ahmed El Maanouni

EDITING: Martine Chicot

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Ahmed El Maanouni

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Nass el Ghiwane

SOUND: Ricardo Castro

PRODUCTION DESIGN: Rabii Films

STARRING: Toualàa villagers (Oulad Ziane) in the Casablanca region, and in particular: Abdelwahad and his family, Tobi, Afandi Redouane and Ben Brahim

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Morocco

LANGUAGE: Arabic, French with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: B&W

RUNNING TIME: 90 minutes

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with Ahmed El Maanouni. Restoration funded by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

Alyam, Alyam is a film about shattered dreams and the circumstances leading up to that point; about the shaking of the traditional social structure; about the strength born of desperation and the unrelenting dissipation of lost generations. This is stressed from the first notes of the opening music, by the strangely empty building frame that is slowly filled with people, by the village space, by the silence of the wandering woman who smokes, until the last shot of the film, when a crowd appears from behind a deserted hill. The dreams of a society growing smaller, unable to hold on to the resources that could help it survive, are mirrored by the mother’s helpless prayer, “I need your shadow, I need your light, I need your face.”

I simply wanted to show the farmers’ faces, to honor their sounds and their images, their silences and their words, and that’s why I chose not to interfere and to opt for deliberately restrained composition, movement and mise-enscène. I tried to minimize the camera’s ability to distort, make a point, or discriminate. I wanted each aspect to be presented equally. I did not look for spectacular beauty, but made an effort to let the imagery of the rural world speak through abstraction and silence.

Almost 40 years later, when I watch Alyam, Alyam again, I am still comfortable with my aesthetic choices and my intuitions, but I cannot avoid noticing how, from beginning to end – from the opening shots with the blood shed by the camels, to the crowd of peasants appearing from behind the hills – it all seemed to presage the current tragedy experienced by the thousands whose broken dreams lie at the bottom of the Mediterranean, on which the voice of Nass El Ghiwane’s Larbi Batma seems to strangely resonate: “Alyam, Alyam, oh, those were the days! Why are you crossed? Who changed your course? You were once sweet like milk, now you’re bitter. I love all men as if they were my brothers. My brothers have crushed me. I will silence my pain and let my love be loud.”- Ahmed El Maanouni

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Alyam, Alyam used the 16mm A/B rolls original camera and sound negatives preserved at Eclair Laboratories, where the 4K scan was performed. Restoration - carried out at Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata - succeeded in stabilizing the image and bringing the original chromatic qualities to light. Director Ahmed El Maanouni supervised the color grading process and approved the final restoration.

BADOU BOY

Director: Djibril Diop Mambéty

WRITTEN BY: Djibril Diop Mambéty

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Baidy Sow

STARRING: Laminé Ba, Al Demba Ciss, Christoph Colomb, Aziz Diop Mambéty

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Senegal

LANGUAGE: French and Wolof with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 56 miniutes

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata and L’Image Retrouvée laboratories in association with Teemour Diop Mambéty. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO—in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna—to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

BADOU BOY was restored in 4K using the internegative and the sound negative. Color grading was supervised by Pierre-Alain Meier.

Restoration work was carried out in 2021 at L'Immagine Ritrovata and L'Image Retrouvée laboratories.

With special thanks to Teemour Diop Mambéty.

BLACK GIRL

LA NOIRE DE...

Director: Ousmane Sembène

WRITTEN BY: Ousmane Sembène

EDITING: André Gaudier

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Christian Lacoste

ASSISTANT CAMERAMAN: Ibrahima Barro

STARRING: Mbissine Thérèse Diop, Anne-Marie Jelinek, Robert Fontaine, Momar Nar Sene, Ibrahima Boy

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Senegal

LANGUAGE: French with English Subtitles

COLOR INFO: B&W

RUNNING TIME: 65 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Les Films Domirev

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/ L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with the Sembène Estate, Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, INA, Eclair laboratories and the Centre National de Cinématographie. Restoration funded by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

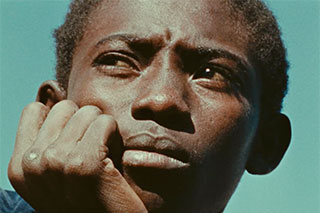

Black Girl, or La Noire de…, was the first of Ousmane Sembène’s pictures to make a real impact in the west, and I can clearly remember the effect it had when it opened in New York in 1969, three years after it came out in Senegal. An astonishing movie—so ferocious, so haunting, and so unlike anything we’d ever seen.

- Martin Scorsese, May 2015

I am not for “social realism” nor for a “cinema of signs” with slogans and demonstrations. For me revolutionary cinema is something else. If we managed to set up a group of cinéastes who all make cinema directed in the same direction, I believe that then we could influence a little bit of the destinies of our country. I think that the film, more than the book, can crystallize an awakening within the masses. I am personally inspired much by the example of Brecht.

- Ousmane Sembène

In 1961, shortly after Senegal declared its independence from France, Ousmane Sembène, a self-educated dockworker, assigned himself an impossible task: to create a true African cinema as a “night school” for his people. is explosive debut—a film described as the first African feature (true in spirit, if not in fact)—inspired a form of fearless, socially engaged, and uncompromising cinema across the globe. La Noire de … (Black Girl) follows a young girl lured to France by a white bourgeoisie couple, who keep her locked in their flat as a housekeeper. As the daily and unrelenting indignities unfold, Diouana, the title character, literally loses her voice. Sembène highlights her silence, familiar to the voiceless across the globe, yet reveals Diouana’s immense dignity and, by the end, agency. He draws visually from the French Nouvelle Vague (in a film about racial and class divides, the black-and-white photography carries new power) and spiritually from the Italian neorealists, but the film’s heart and soul is African. By turning around the camera—used for 100 years to demean Black people—Sembène offers us the first humanistic gaze at Africans.

But the film (shot mostly in Dakar) also remains a seminal work of cinematic art, as it unfolds with startling precision and decisiveness, providing revealing, unforgettable and richly metaphoric perspective on a never-beforeseen Africa. La Noire de … became a sensation at festivals from Carthage to Pyongyang, and Sembène became the first non-French recipient of the Prix Jean Vigo, given previously to Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard. In the film’s culminating moment, a boy grabs a mask and haunts the white businessman who entrapped Diouana. As this child pulls the mask from his face, we wonder: Will a new Africa emerge? Nearly 50 years after its initial screenings, the visionary La Noire de … remains a gorgeous, shocking and of-the-moment African story.

- Samba Gadjigo and Jason Silverman

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of La Noire de… was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negative provided by INA and the Sembène Estate and preserved at the CNC – Archives Françaises du Film.

In order to try and minimize the presence of visible spots (due to processing errors and aggravated by time) and scratches on the image, the camera negative was wet-scanned at 4K resolution. Due mainly to these two issues, the digital restoration required considerable efforts. A vintage print preserved at the Cinémathèque Française was used as reference.

Borom Sarret

Director: Ousmane Sembène

WRITTEN BY: Ousmane Sembene

EDITING: Andre Gaudier

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Christian Lacoste

ASSISTANT CAMERAMAN: Ibrahima Barro

FROM: INA/Éclair/Cineteca/Sembene Family

STARRING: Ly Abdoulay, Albourah

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Senegal

LANGUAGE: French and Wolof

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 22'

ON COMPANY: INA

Restored in 2013 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and Laboratoires Éclair, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, and the Sembène Estate. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

I think given the fact that there is such a diversity of languages in Africa, we, African filmmakers, will have to find our own way in order to ensure that the message be understood by everyone, or we’ll have to find a language that comes from the image and the gestures. I think I would go as far as to say that we will have to go back and see some of the silent films and in that way find new inspiration.

Contrary to what people think, we talk a lot in Africa but we talk when it’s time to talk. There are also those who say blacks spend all of their time dancing – but we dance for reasons which are our own.

Dancing is not a flaw in itself, but I never see an engineer dancing in front of his machine, and a continent or a people do not spend its time dancing.

All of this means that the African filmmaker’s work is very important – he must find a way that is his own, he must find his own symbols, even create symbols if he has to.

[...] I then realized Borom Sarret, my first true short film. It is the story of a cartman who is, to some extent, the taxi driver of a horse-drawn cart. Confronted by a rich customer in a residential district prohibited to such a type of vehicle, a cop stops him, makes a complaint, and seizes the cart. Relieved of his livelihood, the poor fellow remains sadly in his place. His wife entrusts the guardianship of their children to him while saying to him “We will eat this evening…” For this I got the first work prize at the Festival of Tours in 1963.

-Ousmane Sembène

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Borom Sarret was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negatives provided by INA and preserved at Éclair Laboratories.

The film was scanned in 4K at Éclair Laboratories and restored at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory. The image was digitally stabilized and cleaned, and all wear marks were eliminated. Image grading helped recover the richness of the original cinematography.

After scanning, the sound was digitally cleaned and background noise reduction was applied to eliminate all wear marks, without losing any of the dynamic features of the original soundtrack.

The World Cinema Foundation would like to specially thank Alain Sembène and the Sembène Family for facilitating the restoration process.

Image: © Courtesy of INA

BOYS FROM FENGKUEI, THE

FENG GUI LAI DE REN

Director: Hou Hsiao-hsien

WRITTEN BY: T'ien-wen Chu

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Kun Hao Chen

SOUND: Duu-Chih Tu

STARRING: Chun-fang Chang, Shih Chang, Doze Niu, Chao P'eng-chue, Chung-Hua Tou, Li-Yin Yang

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Taiwan

LANGUAGE: Mandarin with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 101 minutes

Restored by the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique in collaboration with Hou Hsiao-hsien and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY, A

GU LING JIE SHAO NIAN SHA REN SHI JIAN

Director: Edward Yang

WRITTEN BY: Edward Yang, Yan Hangya, Yang Shunqing, Lai Mingtang

EDITING: Chen Bowen

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Zhang Huigong, Li Longyu

FROM: Central Motion Picture Corporation, Taipei

STARRING: Zhang Zhen (Xiao Si’r), Lisa Yang (Ming), Zhang Guozhu (Zhang Ju), Elaine Jin (Mrs Zhang), Wang Juan (Elder Sister), Ke Yulun (Airplane), Tan Zhigang (Ma)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Taiwan

LANGUAGE: Mandarin and Taiwanese with French and English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 237 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Yang and His Gang Filmmakers

SET DESIGNER: Yu Weiyan, Edward Yang

Restored in 2009 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Central Motion Picture Corporation, and the Edward Yang Estate. Scan performed at Digimax laboratories in Taipei. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

It is easy to restore a film’s image, but much harder to revive that feeling of seeing a classic for the first time. Fifteen years ago, Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day was released, heralding a new talent in world cinema. Each year since has further confirmed its status as a classic, but at the cost of increased wear and tear on the prints. Restoration is usually reserved for relics from decades ago. But sometimes we need to dust off recent memories to remind us how brightly the not too distant past shined. Thanks to the latest digital technology, we can seize these celluloid moments even as they begin to slip irrevocably from our grasp. In June of 2007 when he was only 59 years old, we lost Edward Yang forever. I’m very happy that A Brighter Summer Day has been restored so a new generation of filmgoers can feel the excitement of seeing it for the first time. –Wong Kar-Wai, May 2009

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of the uncut version of A Brighter Summer Day used the original 35mm camera and sound negatives provided by the Edward Yang Estate and preserved at the Central Motion Pictures Corporation in Taipei. Due to the deterioration of the original camera negative an intermediate of the film printed at the time was also used. The digital restoration produced a new 35mm internegative.

Image: © Courtesy of Edward Yang Estate/CMPC

CAMP DE THIAROYE

Director: Ousmane Sembène and Thierno Faty Sow

WRITTEN BY: Ousmane Sembène and Thierno Faty Sow

EDITING: Kahéna Attia

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Smaïl Lakhdar-Hamina

PRODUCER: Mustafa Ben Jemja, Ouzid Dahmane, Mamadou Mbengue

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Ismaël Lô

STARRING: Sidiki Bakaba, Hamed Camara, Ismaila Cissé, Ababacar Sy Cissé, Moussa Cissoko, Eloi Coly, Ismaël Lô, Pierre Londiche

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Senegal, Algeria, Tunisia

LANGUAGE: German, French, Wolof, English

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 153 minutes

PRODUCER: Mustafa Ben Jemja, Ouzid Dahmane, Mamadou Mbengue

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with the Tunisian Ministry of Cultural Affairs and the Senegalese Ministry of Culture and Historical Heritage. With special thanks to Mohamed Challouf and Association Ciné-Sud Patrimoine. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

CAMP DE THAIROYE was restored in 4K at L'Immagine Ritrovata using a second-generation internegative and the original sound negative, preserved at the Tunisian Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

CHESS OF THE WIND

SHATRANJ-E BAAD

Director: Mohammad Reza Aslani

WRITTEN BY: Mohammad Reza Aslani

EDITING: Abbas Ganjavi

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Houshang Baharlou

PRODUCER: Bahman Farmanara

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Sheyda Gharachedaghi

ART DIRECTOR: Houri Etesam

STARRING: Fakhri Khorvash, Shohreh Aghdashloo, Shahram Golchin, Mohamad Ali Keshavarz, Hamid Taati, Akbar Zanjanpour

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Iran

LANGUAGE: Farsi

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 93 minutes

PRODUCER: Bahman Farmanara

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Image Retrouvée laboratory (Paris) in collaboration with Mohammad Reza Aslani and Gita Aslani Shahrestani. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

Shatranj-e Baad might be one of the most emblematic films in the history of Iranian cinema, even though its visibility was limited to a disastrous preview at Tehran International Film Festival in 1976. Due to an artistic conflict between Aslani and the festival curator, the projection was sabotaged, its reels were disrupted and projector malfunctioned. The critics walked out during the screening, as did the jury who pulled the film out of the competition. Instantly deemed elitist, the film was refused by all the distributors. Discouraged, the producer didn’t bother sending the film to the international festivals. In subsequent private showings, Henri Langlois, Roberto Rossellini and Satyajit Ray had the opportunity to see the film in proper condition and congratulated the young director. After that, Shatranj- e Baad, was never screened again. Following the establishment of the Islamic government in 1979, the film was banned because of its non-Islamic content and the reels were subsequently declared lost. There was only a censored VHS, of very poor quality, circulating through informal channels. Although the film rested in obscurity for a long time, its aesthetic value was rediscovered in 2000 by a new generation of critics and cinéphiles who classed it as one of Iran’s lost cinematic masterpieces. Shatranj-e Baad is a singular film, at the confluence of the aesthetics of Visconti and Bresson. The influence of painting can be found in each shot and the careful screenplay toys with multiple plot twists. It was only in 2015 that Aslani found the negatives of Shatranj-e Baad, quite by chance at a flea-market for vintage film costumes and accessories. He bought the reels and immediately sent them to France where they could safely be restored. Now we can fully rediscover all the originality and modernity of this fascinating film, which has spent almost 45 years in the shadows.

- Gita Aslani Shahrestani

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The 4K restoration of CHESS OF THE WIND was completed using the original 35mm camera and sound negatives. Color grading required meticulous work, notably reels 9 and 10 which called for an orange-tinting effect reminiscent of early silent cinema. The restoration was closely supervised by Gita Aslani Shahrestani and Mohammad Reza Aslani; the film's cinematographer Houshang Baharlou also contributed to the grading process.

CHRONICLE OF THE YEARS OF FIRE

WAQAI SANAWAT AL-DJAMR

Director: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina

WRITTEN BY: Rachid Boudjedra, Tewfik Fares, Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Marcello Gatti

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Philippe Arthuys

STARRING: Yorgo Voyagis (Ahmed), Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina (Milud), Leïla Shenna (moglie di Ahmed), Cheikh Nourredine (Si Larbi), Larbi Zekkal (Smaïl), Sid Ali Kouiret, Nadia Talbi, Taha El Amiri, Abdelhalim Rais, Brahim Hadjadj, Hassan El Hassani

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Algeria

LANGUAGE: Arabic and French with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 177 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: ONCIC (Office National Commerce Industrie Cinéma)

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Image Retrouvée and L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratories. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

I tried to recount, with dignity and nobility, this uprising that then became the Algerian Revolution, an uprising not only against the coloniser, but against a certain human condition. I wanted to avoid any kind of Manichaean, caricatural and demagogic approach, which risked turning Waqai sanawat al-djamr into a sort of Western; good against evil, Algerians against French. What guided me was the quest for honesty: I looked inside myself for the honesty of a child, the eyes of the child I once was, the memories of my childhood. […] It would be a serious mistake to distinguish Algerian Cinema, the cinema of the Maghreb, from African Cinema. The cinema of the Third World is one – the Arab World, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, Asia – as we share the same motivations, the same difficulties, and a common destiny, on an artistic level and on an expressive level. We have suffered hunger and thirst. We will reclaim our image.

Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, interviewed by Claude Dupont, “Cahiers de la cinémathèque”,

Summer 1975

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Restored in 4K from the original camera and sound negatives and a first generation 35mm interpositive provided by the filmmaker.

Three different cuts exist of this film: upon Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina's wish, this restoration reconstructed the version that was awarded the Palme d'or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1975.

The original camera negative, outtakes from the same element, and the interpositive were integrated to match a 35mm vintage print provided by the filmmaker as a reference. Color grading was supervised by Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina.

CLOUD-CAPPED STAR, THE

MEGHE DHAKA TARA

Director: Ritwik Ghatak

WRITTEN BY: Ritwik Ghatak

EDITING: Ramesh Joshi

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Dinen Gupta

PRODUCER: Ritwik Ghatak

ART DIRECTOR: Ravi Chatterjee

STARRING: Supriya Choudhury, Anil Chatterjee, Bijon Bhattacharya, Gita De, Gita Ghatak, Dwiju Bhawal, Niranjan Roy

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: India

LANGUAGE: Bengali

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 127 minutes

PRODUCER: Ritwik Ghatak

Restored by the Criterion Collection in cooperation with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the Cineteca di Bologna.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

A new digital transfer was created from the 35 mm original camera negative, preserved at the National Film Archive of India in Pune. This element includes several shots inserted from a duplicate negative. A 35 mm print from the Library of Congress was used for sections of the film where the original camera negative was damaged or incomplete.

The original monaural soundtrack was remastered from the Library of Congress’s print and a digital source from the British Film Institute