Original Poster Ten Cents a Dance (1931)

When I was the director of the New York Film Festival, I got used to hearing the same question posed annually. One year, it was phrased like this: “You’ve been accused of running an ‘auteurist’ festival. How do you feel about that?” My answer was always the same: “If you mean do we show films made by human beings who create individual artistic responses to the world around them, then I plead guilty as charged.” The question was never meant maliciously, but in that spirit of obligatory equanimity that is a fixture of modern journalism. But lingering behind the question is the familiar spirit, always with us in ever-mutating forms, of condescension to art.

This condescension is even present in the stated attitudes of cultural institutions that resort to high-flown rhetoric as justification for their existence—art can “enlighten” us and “touch the soul” and “enrich our lives,” all of which is so vaguely obvious as to be beside the point, and incidental to what art is and does.

Art will always be fragile, no matter what the political or cultural climate. It will always be called upon to financially justify itself, to demonstrate its “relevance,” to prove its adherence to this or that social doctrine or movement no matter how worthy, and it will always be open to charges of “elitism” from those opportunistic enough to make them.

At a moment like this one—today, January 13, 2021, in the United States of America—art will be seen as beside the point. In terms of the immediate and pressing reality, that’s obviously the case. But art lingers as a powerful, looming presence in the background of all moments of upheaval, and, I would wager, in the lives of many people who are now engaged in debate on the floor of the House of Representatives.

“St. Thomas Aquinas says that art does not require rectitude of the appetite, that it is wholly concerned with the good of that which is made,” wrote Flannery O’Connor. “He says that a work of art is a good in itself, and this is a truth that the modern world has largely forgotten. We are not content to stay within our limitations and make something that is simply a good in and by itself. Now we want to make something that will have some utilitarian value.” But the utilitarian value of an individual novel or painting or film is always incidental and has a short expiration period. When it’s at its most powerful, it doesn’t confirm or rebut or prove or disprove or condemn or celebrate anything. It takes on a life of its own and poses a cosmic, unanswerable question. It sees, it reveals itself before us, and it makes us shiver.

Over the years, Martin Scorsese and Margaret Bodde and Jennifer Ahn and the members of The Film Foundation’s board have been asked multiple variations on the question “Is film restoration necessary?” The question is always posed in the same spirit that I mentioned above. And it’s always best answered with another question: if you recognize the value of cinema, then how could film restoration not be necessary?

The cinema doesn’t put food on the table. It doesn’t provide for the common defense or keep the trains running on time or resolve territorial disputes. To paraphrase Daniel Berrigan, it is useless in the sense that God is useless, because neither are part of the kingdom of necessity.

The Film Foundation has participated in, facilitated and commissioned the restorations of so many films. Here are some images from a few of the most fragile.

THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR (India, 1960, d. Ritwik Ghatak)

Restored by the Criterion Collection in partnership with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the Cineteca di Bologna, from elements preserved by the National Film Archive of India.

THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES (Armenia, 1969, d. Sergei Parajanov)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, in association with the National Cinema Centre of Armenia and Gosfilmofond of Russia. Restoration funded by the Material World Charitable Foundation.

LOST LOST LOST (1976, d. Jonas Mekas)

Preserved by Anthology Film Archives through the Avant-Garde Masters program funded by The Film Foundation and administered by the National Film Preservation Foundation.

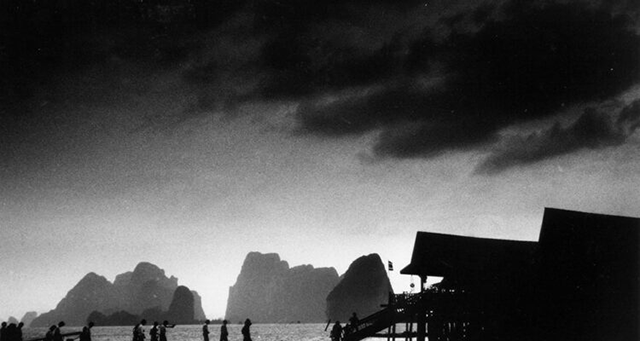

MYSTERIOUS OBJECT AT NOON (Thailand, 2000, d. Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Restored in 2013 by the Austrian Film Museum and Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, LISTO laboratory in Vienna, Technicolor Ltd in Bangkok, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

TOUKI BOUKI (Senegal, 1973, d. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Restored in 2008 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the family of Djibril Diop Mambéty. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

VOICE IN THE WIND (1944, d. Arthur Ripley)

Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation, in collaboration with Cohen Film Collection. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

THE WAY TO SHADOW GARDEN (1954, d. Stan Brakhage)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

In a 1965 television interview with the European correspondent Irving R. Levine, Federico Fellini spoke of attempting through his work to orient his viewers in the direction of “inner liberation.” In the commercialized debasement of his own moment of peak popularity, this endeavor (for lack of a better word) was obscured by the tendency to sell the outer trappings of the films, and to sell Fellini himself as a grand showman or ringmaster, an amalgamation of La Dolce Vita’s Marcello riding on a young woman’s back at the orgy that never quite gels, 8 ½’s Guido wielding a bullwhip to subdue his fantasized harem, and perhaps the kindly onscreen narrator in Amarcord. In the late 60s and early 70s, Fellini was conjoined with Stanley Kubrick (who he greatly admired) and filmmakers as various as Nicolas Roeg, Ken Russell, Alexander Jodorowsky and Kenneth Anger as masters of cinema as mass hypnosis, film-as-acid-trip. But the inner liberation that Fellini discusses in the Levine interview is precisely the opposite of mind-expanding drug use or unbridled sexual freedom. Fellini’s films radiate a spiritual impulse that is closer to the writings of Thomas Merton than the pronouncements of Timothy Leary or Wilhelm Reich. In more than one film, he actually managed to describe a series of all-too-human, self-destructive delusions in the most generous terms imaginable, and maintained a fairly miraculous balance between the bewitching spectacle and pageantry of human chaos and the sadness and desperation beneath the surface.

In the last few days, my wife and I have gone through many of the titles in Criterion’s magnificent new Essential Fellini box set. It’s been a revelatory experience for both of us. Last night we looked at La Dolce Vita, which was restored by the Cineteca di Bologna in collaboration with The Film Foundation and funding by Gucci. This was the Fellini film that took the world by storm (and that actually coined the term “paparazzi”). La Strada and 8 ½ may be the greater films, but La Dolce Vita is a powerfully moving experience, a pageant of delusions playing out in the heady landscape of Rome at the end of the 50s that today seems more sad and deeply soulful than spectacular.

As I write these last words, masses of Americans suffering from a very different type of delusion are storming the Capitol building. One day, years from now, when someone makes fiction out of this chilling moment, let’s hope that it’s a filmmaker with the artistry and the soul and the sensitivity of Federico Fellini.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

LA DOLCE VITA (1960, d. Federico Fellini)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in association with The Film Foundation, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia-Cineteca Nazionale, Pathé, Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, Mediaset-Medusa, Paramount Pictures and Cinecittà Luce. Restoration funding provided by Gucci and The Film Foundation.

LA STRADA (1954, d. Federico Fellini)

Restored in 4K resolution by the Criterion Collection and The Film Foundation at Cineteca di Bologna’s L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory from a 35mm dupe negative preserved by Beta Film GmbH. Restoration funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

Two films from avant-garde film renaissance of the late ’90s, Peggy Ahwesh’s Nocturne (1998) and Jesse Lerner’s Ruins (1999), join ten shorts made by Bay Area women artists to be preserved through the 2020 Avant-Garde Masters Grants, awarded by The Film Foundation and the National Film Preservation Foundation.

UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive will preserve ten films that were distributed by the Bay Area–based Serious Business Company (SBC), an independent film distribution company founded by Freude (1942–2009), operating from 1972 to 1984. Among them is Gunvor Nelson’s masterpiece My Name is Oona (1969). Named to the National Film Registry in 2019, this portrait of the artist’s daughter uses a repetitive soundtrack and rhythmic editing to capture the joyful chaos of childhood. Also distributed by SBC and slated for preservation are Alice Anne Parker’s I Change I Am the Same (1969), a playful critique of clothing and gender roles, four films exploring domesticity and the artistic life made by Freude, Josie Winship’s animated Bird Lady vs. the Galloping Gonads (1976), Karen Johnson’s Orange (1970), and Judith Wardwell’s satirical take on America’s sanitation obsession, Plastic Blag (1968).

Peggy Ahwesh’s Nocturne evokes gothic literature and horror film history, weaving stark black-and-white imagery with footage taken with a PixelVision video camera. The dreamlike narrative mixes text and spoken word to create a minimalist psychological horror film. Anthology Film Archives is supervising the preservation and will premiere the new print as part of a Peggy Ahwesh retrospective alongside other films preserved through NFPF programs.

XFR Collective will oversee the preservation of Jesse Lerner’s feature-length collage essay Ruins. Mostly comprised of archival footage, Ruins is a mischievous melding of fact and fiction that takes on the trappings of traditional museums. It explores the way history is constructed by official means and pokes holes in those narratives with wit and bite.

Now in its 18th year, Avant-Garde Masters was created by The Film Foundation and the NFPF to save films significant to the development of the avant-garde in America. Funding is generously provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. The grants have preserved 200 works by 78 artists, including Kenneth Anger, Shirley Clarke, Bruce Conner, Joseph Cornell, Oskar Fischinger, Hollis Frampton, Barbara Hammer, Ernie Gehr, George and Mike Kuchar, and Carolee Schneemann. A full list of films preserved through the program can be found here.

The start of talkies in 1929 in Hollywood jumpstarted Lionel Barrymore’s brief career as a director as studios required an experienced hand with spoken dialogue and Barrymore had had great success on stage before he became a movie actor. Ten Cents a Dance was the last movie he directed, and he was offered the job after being nominated for a directing Oscar for Madame X in 1930.

The shoot was plagued with difficulty including health problems for the director and star. Barbara Stanwyck, the leading lady, fractured her pelvis and was sidelined for a few days. But Barrymore suffered from chronic arthritis and was in constant pain. In the biography “The Barrymores: The Royal Family in Hollywood,” author James Kotsilibas-Davis writes, “Heavy medication dulled his pain and his direction. ‘You’d start a scene and look around and find he’d fallen asleep,’ leading man Ricardo Cortez states. ‘He tried his best,’ recalls Barbara Stanwyck. ‘As a performer, you just had to try harder.’ At the Hollywood preview, somebody transposed the reels, and the picture was run backward. Rumors circulated that Barrymore had lost his wits. Eventually, hung together correctly, Ten Cents a Dance became a personal success for Columbia’s new star.”

But Barrymore was disillusioned with directing and returned to acting, something he referred to as “the family curse.” In a New York Times interview in 1930, Barrymore said, “I have been with pictures for 21 years and don’t yet understand what the public wants. I tried, but the public taste is a riddle to me. It’s easy to fail ... Mind you, I don’t admit failure as a director, I don’t think I did, but I refuse to assume the burden of production. It wears a man down too fast.”

He would win the Best Supporting Actor Oscar the following year for A Free Soul.

Barrymore did Ten Cents a Dance no favors. Graced with a winning actress and a very good writer, Jo Swerling (who also wrote Platinum Blonde, The Pride of the Yankees, It’s a Wonderful Life and the Tony-winning Guys and Dolls on Broadway), the Pre-Code film is badly paced and misses every opportunity to show off Stanwyck’s natural talent. (Eddie Buzzell, a Columbia director, was hired to punch up the comedic scenes.)

Stanwyck plays Barbara O’Neill, a worldly-wise taxi dancer at a dancehall who attracts the eye of rich Bradley Carlton (Ricardo Cortez), who is willing to tip her $100 just to talk to her. Unfortunately, as whipsmart as Barbara is at the dancehall, her brains turn to mush when she meets a fellow lodger at her boarding house, college student Eddie Miller (Monroe Owsley). Eddie gives her a sob story, she gives him her $100 tip, and before you know it, the two are married. Eddie starts out no good and progresses to being worse. Barbara asks Bradley to employ him, the two hide their marriage from everyone, Eddie makes her leave her job at the dance hall, then he loses their money with some shady deals with shady friends on the stock market, embezzles from Bradley, tries to skip town, is saved by Barbara who tries to sell her virtue to Bradley for $5,000 and when Eddie ungratefully takes the money and then tries to blackmail Bradley, then Barbara’s eyes are opened, and she leaves him for Bradley.

But the movie does have its pleasures. Stanwyck is completely appealing as Barbara and is given a lot of snappy dialogue. “What’s a guy gotta do to dance with you girls?” asks a sailor of Stanwyck. “All you need is a ticket and some courage” is her comeback. Describing the manager of the dancehall, she has this to say to Bradley: “She’s got to keep the place hot enough to avoid bankruptcy and cold enough to avoid raids.” When things unravel between Barbara and Eddie, she retorts, “You’re not a man. You’re not even a good sample.” And when Barbara asks Bradley for the $5,000 promising to pay him back, he says incredulously, “At ten cents a dance? That’s 10,000 dances!”

The original poster had this tagline in all caps: SHE WAS A DANCE HALL HOSTESS BUT THE BAND NEVER PLAYED ‘HOME SWEET HOME’ FOR HER! Stanwyck, with top billing above the title in only her fifth movie role, poses in an evening gown, one strap of her bodice falling off her shoulder. Other ads were even more metaphorically bodice-ripping. ‘With a lump in her throat and a pang in her heart ... SHE DANCED!’ screamed a print ad in the Toledo News Bee of April 3, 1931. ‘BLISS FOR A MOMENT... AND THEN REMORSE!’ was another one. ‘She dreamed her way to paradise ... but danced a path to torment’ was yet another.

Original Poster Ten Cents a Dance (1931)

Ricardo Cortez was the stage name for Jacob Krantz, the son of Austrian immigrants, who jettisoned his Jewish name in favor of one bestowing a Latin lover persona to match his dark good looks. After all, this was the time when Rudolf Valentino and Ramon Navarro were matinee idols. Cortez mostly played villains in his career and is best known for playing Detective Spade in 1931’s The Maltese Falcon. (By the way, Stanwyck was born Ruby Stevens.)

Owsley, who died of a heart attack at age 36, was Hollywood’s go-to guy when they were casting a cheating liar. In fact, he played another such cheat in another 1931 film with a similar storyline. In Honor Among Lovers, Claudette Colbert lives to regret her marriage to Owsley and ends up with her boss Frederic March.

The movie started out with different titles – Roseland was one, Anybody’s Girl was another. But the release title was taken from a popular song of the time written by Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart for Florenz Ziegfeld’s play “Simple Simon” and sung by Ruth Etting in the 1930 production. Her version was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999. It was also inducted into the National Recording Registry in 2011. As an aside, the song was actually written for a different singer, Lee Morse, who was unable to perform it when she showed up drunk at the Boston tryouts. Etting stepped in for her at Ziegfeld’s request, and history was made.

The film was preserved with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association in association with The Film Foundation. The source material for the preservation was the nitrate original picture and track negatives. Picture and sound master positives were made from these negatives as were two show-quality access prints.