News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

About 25 years ago, a writer I knew gave me a call. He was writing a piece about film restoration and he was taking a contrarian’s point of view. He didn’t have a problem with the actual practice of restoration and preservation per se, but with the advocacy for the practice. He had a Darwinian perspective: he maintained that the best films would always be cared for because they were the ones that had stood the test of time, while the less good ones would simply fall by the wayside and go the way of extinct species like the Perenian Ibex or the Dodo. I listened patiently, and then explained to him, as calmly and in as much detail as I could, that he was out of his mind.

There was the fragility of film itself, and the many ways that earlier stocks could deteriorate. There was the reality of vault fires, which had destroyed the negatives of many films that were long considered classics. There was the fact that the greatness of certain films was recognized only long after their initial releases, at which point they were deemed disappointments or failures—that list is endless, but The Night of the Hunter, which we covered a few months ago, is a perfect example.

And then there’s the question of changing standards. At this moment, there is a great obsession with “accessibility.” Is a given film too “esoteric?” Does it only appeal to the “elitist tastes” of “auteurists?” Such clichés are now rampant. At the highest levels on the accessibility meter would be films made within the last 10 years, officially sanctioned by the AFI or AMPAS (English language only, of course). At the very lowest levels would be avant-garde cinema, whose audiences are always small, dedicated and tightly knit. And within the world of the avant garde, the early work of the great Canadian musician, visual artist and filmmaker Michael Snow would surely register near zero. If one were to follow my old acquaintance’s test of restoration worthiness, the negative for Snow’s 1969 film <_ _ _>, also known as Back and Forth, would be wedged into the bottom of the stack at the darkest corner of a mildewed cellar. “This is the worst kind of art film,” begins the synopsis on the Directors’ Fortnight website (probably written by the filmmaker). “BACK AND FORTH takes place almost entirely in an empty classroom. Various people show up now and then. The gimmick here is that the camera continuously moves back and forth, at an ever-increasing rate of speed, and by the end of the picture everything’s just a blur.” In a 2007 interview, Snow fondly recalled a 1969 MoMA screening. “10 minutes into it a guy jumped up and said, ‘This is basically a piece of shit, I want this stopped,’ and another guy said, ‘Shut up, we want to watch this.’ They were facing each other and they started to fight. There were 20 or so people in the audience, all of whom got up and left once they started fighting.”

<_ _ _>, which was restored by Anthology Film Archives with the assistance of The Film Foundation (Anthology is now at work on Snow’s earlier Wavelength), brings to mind Snow’s frequently quoted 1967 statement: “My paintings are done by a filmmaker, sculpture by a musician, films by a painter, music by a filmmaker, paintings by a sculptor, sculpture by a filmmaker, films by a musician, music by a sculptor … sometimes they all work together.” A flat-screen kinetic sculpture, a plunge into the heart of perception itself, a transformation from the absolutely mundane into the uncanny right before our eyes… As a student, I remember the amazement of watching this film for the first time on a KEM. Was I going to run out and rave about it to all my friends who weren’t into movies? No. Was I going to call my parents and tell them to see it (if they only could) and take all their friends? Nope. Did I have an issue with the commercial film industry for “marginalizing” Snow’s work? No—two separate worlds. Was it “accessible?” Well, it was accessible to me, an audience of one. And if I reject the term “elitist” as a means of describing my solitary experience, that’s because I’ve come to see that it’s always a matter of one person at a time, with all the arts. Even a “mass art form” like the cinema—it’s great to experience anything in a crowded theatre, but in the end it’s always just the movie and you.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

THE NIGHT OF THE HUNTER (1955, d. Charles Laughton)

Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive in cooperation with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. with funding provided by Robert Sturm and The Film Foundation.

BACK AND FORTH (1969, d. Michael Snow)

Restored by Anthology Film Archives with funding provided by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and The Film Foundation.

WAVELENGTH (1967, d. Michael Snow)

Restored by Anthology Film Archives and The Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

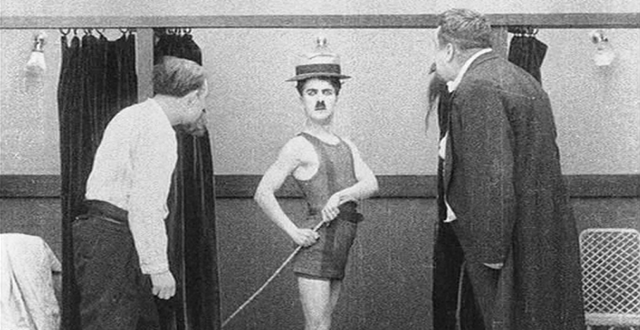

On a couple of occasions, The Film Foundation has facilitated or participated in two restorations of the same film, the first photochemical and the second digital. For instance, Chaplin’s The Cure and Lubitsch’s Forbidden Paradise, both of which were restored on the first round by MoMA. The digital restoration of The Cure was carried out by the Cineteca di Bologna and L’Immagine Ritrovata, with support from the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation and the Material World Foundation, as part of their massive ongoing Chaplin Project. According to David Shepherd, they gathered sources from all over the world and scanned the best elements for every shot, which they then cleaned and stabilized. Damaged frames or passages were inserted from alternate sources when necessary, the contrast and brightness levels were balanced, the frame rate was corrected and the original title cards were recreated. The careful restoration of any silent film, at this moment in the relatively short history of film restoration, involves something like this process. It also involves making choices. “Each film was shot with two different negatives,” explained Shepherd in a Flicker Alley interview, “with two different cameras: the A negative and B negative. The A negative is clearly the better one. You can tell by little things that Chaplin does that are more clever and detailed in one than the other. We tried to restore to the A negative wherever we could, but if a shot was too damaged to restore, we put in footage from the B negative. If there was more material in the B negative that was because they edited it out in the A original.”

The digital work on Forbidden Paradise, also done at MoMA with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, involved a mixture of detective work, interpretation and creativity that, according to Dave Kehr, restored about 90% of the film’s coherence (two missing scenes were summarized by added intertitles). Anyone who remembers excitedly renting a VHS copy of a rare silent film only to go home to find a nonsensical and arrhythmic assemblage of ragged jump cuts will know what I’m talking about. I vividly remember renting a copy of Murnau’s The Haunted Castle, throwing it in the machine and almost instantaneously crash-landing in a state of absolute bewilderment. Mercifully, that film has been restored as well (another act of reconstruction, in this case by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, working from a nitrate negative and positive).

We know that preservation is an ongoing process, and that we must now constantly migrate preserved elements from one storage medium and/or system to another (bearing in mind that nothing has been proven to last longer than film). But restoration is also ongoing. There will always be new tools, offering increased flexibility and precision…and, inevitably, increased opportunities for choices made in the name of “enhancement” or “improvement” that are often, in the end, creative alterations or outright violations. The plethora of early moving images that have been stabilized and “up-resed” to 4K and 60fps (including films by the Lumière Brothers) is startling to behold, but they raise troubling questions about what images are and the wildly varying levels of respect with which they’re treated.

Going forward, every film will be passed from hand to hand into the future. We have to make sure that there is always love, reverence and humility in the handling.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

THE CURE (1917, d. Charlie Chaplin)

Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art with funding provided by The Film Foundation.

Restored Cineteca di Bologna at L'Immagine Ritrovata, in collaboration with Lobster Films and Film Preservation Associates. Restoration funding provided by The Film Foundation, the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation and the Material World Foundation.

FORBIDDEN PARADISE (1924, d. Ernst Lubitsch)

Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art with funding provided by The Film Foundation and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

Restored by The Museum of Modern Art and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

What exactly do we mean when we say “film culture?” In the broadest sense, it means the community of people across the globe who share a love for the art of cinema. That includes filmmakers, programmers, preservationists, critics, academics, self-described cinephiles and plain old movie fans. Some of us are all of the above put together. For many years, beginning with the introduction of the videocassette, we shared hard-to-find titles through the mail (illegally!), made from the best available sources and possibly upgraded as we went along. This was long before everyone’s eyes were primed for digital sharpness. We were all used to 16mm prints “chained” for television or screened in repertory houses, some of them several thousand light years away from an original or even a dupe negative. Thousands of titles were acquired by companies like Sinister Cinema, which specialized in horror and science fiction and had a good level of quality control. There were also many other fly-by-night companies whose packaging was created with Xerox machines and whose cassettes turned up in abundance at Kim’s Video here in New York. I remember the excitement I experienced when I first saw those titles on the shelves (sorted by filmmaker—the Godard section was labeled “God”). Rossellini’s historical films! Early Mizoguchi!! Straub/Huillet!!! There was the excitement, and then there was the reality of the actual transfer, which was often comically deficient. You would have to squint, very hard, to make out the movement of actors in the frame or to decide whether the dark blur on the left was a tree or a skyscraper. You would find a way to allow for the slurring and warping of imperfect transfers made from imperfect transfers made from ancient broadcasts that had been recorded way back when by someone with a ¾-inch Helioscan deck. As unwatchable as the image often was, the sound was usually worse, a succession of distorted wow-ing utterances and music cues heard through a thickly layered wall of static. At a certain inevitable point, the tracking would fall apart and that would be the end of the “screening.” The homemade tapes that we shared were often just as imperfect. However, it was the sharing that counted.

Edward Yang’s epic film A Brighter Summer Day was one of the titles that floated in the cinephilic ether. Prints were rare. The video copies that circulated were far more acceptable than the extreme cases that I’ve described above, but the version that was most readily available was shortened. Like many of Edward’s films, it remained difficult to see in anything approaching proper conditions for many years, before and after his death.

When I came aboard at the World Cinema Project, the first round of restoration on the film had just been completed by L’Immagine Ritrovata and the Cineteca di Bologna (the WCP later restored Taipei Story). It’s always a great experience to see a film that has been routinely shown under imperfect conditions, carefully restored to something approaching its original state. In this case, it was in Cannes, albeit in the very strangely configured Salle Buñuel (which is wider than it is deep, which means that half the audience has to watch the film from a distorted perspective), in the presence of Edward’s widow Kaili Peng and his son Sean. To see A Brighter Summer Day unfolding on a big screen was startling. It was also, in some way, an affirmation of all those years of sharing imperfect VHS tapes (illegally!), keeping the flame of love for cinema stoked and burning.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY (1991, d. Edward Yang)

Restored in 2009 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Central Motion Picture Corporation, and the Edward Yang Estate. Scan performed at Digimax laboratories in Taipei. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

TAIPEI STORY (1985, d. Edward Yang)

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project at Cineteca di Bologna/L’immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique and Hou Hsiao-hsien.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

1:20PM, January 20, 2021

The 1951 film Journey into Light was independently produced by Joseph Bernhard, who had run the Cinecolor Corporation and United States Pictures, a production division at Warner Brothers, with Milton Sperling. Before his death in 1954, Bernhard was involved in some interesting films, including Cloak and Dagger by Fritz Lang and Japanese War Bride and Ruby Gentry, both directed by King Vidor. Journey into Light, the story of a minister from a small New York town (Sterling Hayden) who hits rock bottom after his wife commits suicide and finds redemption at a mission in Los Angeles, was largely shot on actual locations on Skid Row. Weegee was hired as a technical consultant—according to an item about the production in The Hollywood Reporter, he had “recently made an 11-state tour of skid rows and strip joints.” The film, which was photochemically restored by UCLA, is a spiritual melodrama that plays out in raw reality. Ongoing reality also intruded on the production, which had to shut down when Hayden flew to Washington to appear before HUAC as a friendly witness, an act that haunted him to the end of his days.

I will admit that I chose the film to write about today because of its title.

It is very common to be blasé and hopeless about politics in America. Even now. But no one who has lived through the last four years can honestly say that this day doesn’t represent a sea change. Maybe some people took the inauguration ceremony a couple of hours ago for granted. Speaking for myself, the demonstration of comity, humility and good will moved me to tears. And to see it happening at the Capitol, which was stormed, ransacked, desecrated and turned into a battlefield only two weeks ago today, was overwhelming.

A journey into light.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

JOURNEY INTO LIGHT (1951, d. Stuart Heisler)

Restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Restoration funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and The Film Foundation.