News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

I note that the Wikipedia entry on Tunes of Glory—a 1960 adaptation of James Kennaway’s novel (Kennaway also wrote the screenplay) directed by Ronald Neame and restored by the Academy Film Archive in collaboration with The Film Foundation, Janus Films, and MoMA with funding from the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation—identifies the film as a “dark psychological drama,” a quote from a brief article in TCM’s database. This little turn of phrase, innocuous as it might seem, perfectly embodies what Martin Scorsese calls the “devaluation of cinema.” Such quick, encapsulating descriptions are nothing new of course, but now they’re pervasive, employed as marketing tools and “critical” summations and categories on streaming platforms. Every film now, old or new, is imagined to be reducible to a basic essence, easily describable and thus dismissible. This is the attempted consumerization of the filmgoing experience: every viewing occasion tailored to your tastes and needs.

I use the word “attempted” because, of course, there’s always the simple matter of choice. This is true of so many aspects of the social media/streaming world. I remember a conversation with a younger friend a few years back, who complained about how easy it is to get caught up in Tweet wars. She went on for a bit, and I suggested that she simply drop it—get off of Twitter. For her, it was unthinkable. “You have to participate,” she said. Actually, you don’t.

On the internet, a friend explained to me many years ago, 300 words is a tome. 300 words is not even close to enough to describe the experience of Tunes of Glory. Dramatically speaking, the film is a war of nerves between an upper crust Colonel, newly arrived to lead a Scottish regiment (Kennaway himself had served with the Gordon Highlanders) and a hard-drinking working class major who has come up in the ranks and led the regiment through most of WWII after the death of their colonel in battle. Discipline and tradition and breeding vs. camaraderie and relaxation of rules and hard knocks. Who will break, the delicately constituted Colonel or the beloved and violently impulsive Major? But that's just the bare bones of the conflict. The movie is something else again, a vivid tapestry of reactions and counter reactions that find physical expression in the cloistered world, visually and psychologically, of Scottish military life, and it reaches an astonishing pitch through the acting of John Mills as the Colonel and Alec Guinness as the Major, who cuts an alarming figure with his ginger brush cut, a swaggering, needling, hard-drinking, unruly braggart, who is finally unleashed and dangerous. (Mills and Guinness were supposedly offered each other’s eventual roles and swapped.) Dark? Hardly—the action plays out in vivid color and is emotionally vibrant and electrifying. Psychological? Sure, but again, that’s just the starting point. I saw Tunes of Glory for the first time myself not too many years ago, and I was overwhelmed. For those who choose to actually watch it rather than consume it, you might have a similar reaction.

That’s 505 words, and it doesn’t even scratch the surface.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

TUNES OF GLORY (1960, d. Ronald Neame)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation in collaboration with Janus Films and The Museum of Modern Art. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

The cinema is widely and commonly recognized as a popular art form, but its presence and the breadth of its history in different areas of the world varies wildly. The art form itself is often identified with this country, because ours has been the most spectacular, the most widely exported, and perhaps the most sheerly dynamic in relation to the development of the century: as André Bazin once observed, American society has told itself its own developing story and mythology through its cinema. But the cinemas of Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Russia, China and Japan have been forceful presences in the history of the art form for just as long, and Indian cinema has been a powerhouse. In other parts of the world, production has been fitful, in Africa most of all. Africa is a big continent and there are obviously exceptions, including Egypt and, to a lesser extent, South Africa. But in general, getting a film made in Africa has long been, and continues to be, difficult. With the exception of the quickly and massively produced titles shot on home video equipment that started coming out of Nigeria in the late 80s, African cinema is basically one film at a time, each one financed and produced under unique circumstances. The preservation of African cinema has been especially problematic for just those reasons.

The African Film Heritage Project was launched in 2017, a closely coordinated effort between The Film Foundation, the Cineteca di Bologna—where the effort is spearheaded by the formidable Cecilia Cenciarelli—UNESCO (whose “General History of Africa” project is now in its 7th decade and in preparation with its 9th, 10th and 11th volumes) and FEPACI (Pan African Federation of Filmmakers), which launched a crucial survey of all African film archives. The aim of the AFHP is to locate the elements (mainly in European archives) and then restore and preserve African titles selected by a group of African filmmakers and scholars in coordination with FEPACI. Thus far, AFHP has restored Med Hondo’s Soleil O, which was completed not long before the filmmaker’s death; Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina’s Chronicle of the Years of Fire from Algeria, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1975; Timité Bassori’s 1969 film La Femme au couteau from the Ivory Coast; Jean-Pierre Dikongué Pipa’s Muna Moto from Cameroon; and Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Contras’ City from Senegal. Pre-dating the formation of AFHP, the World Cinema Project arm of The Film Foundation restored Trances and Alyam Alyam by Ahmed Al-Maanouni from Morocco (I focused on Trances a ways back here); Mambéty’s Touki Bouki and Ousmane Sembene’s Borom Sarret and Black Girl, three foundational films from Senegal; and Shadi Abdel-Salam’s Al Momia also known as The Night of Counting the Years, and The Eloquent Peasant, from Egypt. The scope of all these linked initiatives and the dedication behind them is deeply moving, a titanic collective effort to reclaim history on multiple fronts. The majority of these films are revelatory on many levels—for westerners with limited exposure or even knowledge of the fact of Africa’s multiple cinemas, and for African audiences and film students as well. For Aboubakar Sanogo, FEPACI’s North American secretary, this is a crucial element. “The young African filmmakers are at a really important crossroad,” he told Mark Cosgrove. “There has never been more of a passion for making films than now in terms of sheer numbers…What they don’t have access to is the history.” The ultimate goal is that “no African filmmaker can take a camera without seeing a Med Hondo or Sembène or Cissé.” It’s a noble goal for Africa and its cinemas, and a real example to millions living on wealthier continents throughout the world who harbor the sadly mistaken belief that history can be either ignored or discarded or re-molded like a lump of clay. Which always ends in humiliation, disgrace, or tragedy.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

SOLEIL O (1970, d. Med Hondo)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna at L'Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in collaboration with Med Hondo. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation and The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

CHRONICLE OF THE YEARS OF FIRE (1975, d. Mohammed Lakhdar–Hamina)

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Image Retrouvée and L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratories. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

LA FEMME AU COUTEAU (1969, d. Timité Bassori)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

MUNA MOTO (1975, d. Jean-Pierre Dikongué-Pipa)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

CONTRAS’ CITY (1968, d. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Restored in 2020 by Cineteca di Bologna/L'Immagine Ritrovata and The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project in association with The Criterion Collection. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

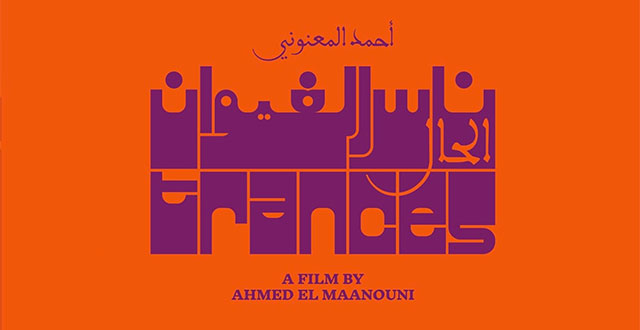

TRANCES (1981, d. Ahmed Al-Maanouni)

Restored in 2007 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, Ahmed El-Maanouni, and Izza Genini. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

ALYAM ALYAM (1978, d. Ahmed Al-Maanouni)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with Ahmed El-Maanouni. Restoration funded by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

TOUKI BOUKI (1973, d. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Restored in 2008 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the family of Djibril Diop Mambéty. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

BOROM SARRET (1963, d. Ousmane Sembène)

Restored in 2013 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and Laboratoires Éclair, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, and the Sembène Estate. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

BLACK GIRL (1966, d. Ousmane Sembène)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/ L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with the Sembène Estate, Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, INA, Eclair laboratories and the Centre National de Cinématographie. Restoration funded by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

AL MOMIA (1969, d. Shadi Abdel-Salam)

Restored in 2009 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, and the Egyptian Film Center. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways, Qatar Museum Authority and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

THE ELOQUENT PEASANT (1969, d. Shadi Abdel-Salam)

Restored in 2010 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, and the Egyptian Film Center. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

‘Transes’ by Moroccan Ahmed El Maanouni available soon on The Criterion Collection

Moroccan director Ahmed El Maanouni’s film “Transes” (Al Hal, 1981), which recounts the stage performances of Moroccan mythic musician group Nass El Ghiwane, is among the new releases to be available soon on “The Criterion Collection” platform, an American home video distribution company which focuses on licensing “important classic and contemporary films.”

“The groundbreaking Moroccan band Nass El Ghiwane is the dynamic subject of this captivating, one-of-a-kind documentary by Ahmed El Maanouni, who filmed the four musicians during a series of electrifying live performances in Tunisia, Morocco, and France; on the streets of Casablanca; and in intimate conversations,” the Criterion Collection said in a statement.

“Storytellers through song and traditional instruments, and with connections to political theater, the band became a local phenomenon and an international sensation, thanks to its rebellious lyrics and sublime, fully acoustic sound, which draws on Berber rhythms, Malhun sung poetry, and Gnawa dances. Both a concert movie and a free-form audiovisual experiment, bolstered by images of the band’s rapt audience, Trances is pure cinematic poetry,” it added.

The 88-minute film was restored in 2007 by the Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, Ahmed El-Maanouni, and Izza Genini.

The Criterion Collection is dedicated to gathering the greatest films from around the world and publishing them in DVD and Blu-ray editions of the highest technical quality, with supplemental features that enhance the appreciation of the art of film.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

Film noir has been so thoroughly fussed over and theorized and fetishized and trumpeted since it was first classified and named back in the 70s that it has now become a brand name. It’s interesting to give the films a fresh look and consider their most outlandish aspects—labyrinthine narratives, wildly eccentric and impulsive characters popping up around every corner, unreliable narrators, resurrections from the dead and soul-searing betrayals. The mixture of resignation, confusion, wild romantic longing, punishing cruelty and sheer craziness really does stop you in your tracks. The titles made in the years just after the war are the most moving, and they now seem directly tied to films about returning WWII vets like The Best Years of Our Lives, Till the End of Time and From This Day Forward—the same bottled-up emotions expressed by different means.

Amnesia, recurring dreams and drug-induced delirium are the narrative convolutions that create fractured landscapes of the mind, often enhanced by filmmakers and actors who were electrified by the challenge. And the challenge is even greater when the source material is from Cornell Woolrich. Woolrich, who also wrote under the pen name William Irish, was prolific. He was also variable. To take one example, his 1940 novel The Bride Wore Black ends with a truly inane “plot twist,” thrown out by François Truffaut in his 1968 adaptation. But he was also inventive, and his novels and short stories were the basis of some of the greatest films of the 40s and 50s, including The Leopard Man, Phantom Lady, Rear Window and The Chase, Arthur Ripley’s 1946 adaptation of The Black Path of Fear. For years, The Chase was only available in some of the worst and most dispiriting transfers I’ve ever seen, and I was thrilled when Bertrand Tavernier told me he’d heard the negative existed in a European archive and overjoyed when the film was actually restored by UCLA with funding from The Film Foundation and the Franco-American Cultural Fund. I wouldn’t dream of giving away too much of the plot. Suffice to say that the film begins with a troubled, penniless vet (Robert Cummings) on the streets of Miami who picks up a wallet on the street and returns it to its rightful owner, a gangster (Steve Cochran) who lives with his beautiful kept wife (Michèle Morgan) in a gaudy mansion filled with “classical” statues, and who decides to give the vet a job as his chauffeur—over the objections of his unimpressed henchman (Peter Lorre)—and test him out with a ride in his specially designed limo in which he can gun the speed from the back. Ripley (who started as a gagman for Mack Sennett, and whose independently made Voice in the Wind was also restored by UCLA with the help of TFF), along with DP Franz Planer, Art Director Robert Usher, writer Philip Yordan and producer Seymour Nebenzal, created an exquisite nightmare that becomes more baroque and uncanny as it unfolds—small wonder that The Chase is a favorite of Guy Maddin. And at the heart of the film is the deep yearning of Cummings’ Scottie to be whole and at peace with himself.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

THE CHASE (1946, d. Arthur Ripley)

Restored by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, with funding provided by The Film Foundation and the Franco-American Cultural Fund, a unique partnership between the Directors Guild of America (DGA); the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA); the Société des Auteurs, Compositeurs et Editeurs de Musique (SACEM); and the Writers Guild of America, West (WGAW).

VOICE IN THE WIND (1944, d. Arthur Ripley)

Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation, in collaboration with Cohen Film Collection. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.