News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

It’s been a while since I’ve seen Jean Renoir’s The Woman on the Beach, but it’s a film that’s never left me, and I was excited to know that The Film Foundation had collaborated on a restoration with the Library of Congress, funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. I remember it discontinuously, in powerful, resonant fragments. “The Woman on the Beach was a perfect theme for treating the drama of isolation,” wrote Renoir in his autobiography. “Its simplicity made all kinds of development possible.” The story, adapted from a novel called None So Blind, is a kind of spiraling dance of death between two men and the woman they both love: a famous painter (Charles Bickford) who has lost his sight in an accident caused by his young wife (Joan Bennett), who seeks the company of a traumatized WWII vet (Robert Ryan) when he crosses her path patrolling a desolate stretch of beach for the Coast Guard. Renoir noted that with his last American film, he had moved away from any ambition to depict “the bonds uniting the individual to his environment,” a constant in his work before and after. “I was embarked on a study of persons whose sole idea was to close the door on that absolutely concrete phenomenon we call life.” The production of the film, recounted in detail by the great film scholar Janet Bergstrom in a 1999 article for Film History, is far more complex than the narrative of the finished film. RKO purchased the rights to the story in serialized form and gave notes to the author, Mitchell Wilson, before it was published as a novel. A script was written and Bennett, set to star, insisted on Renoir as a director, over the strenuous objections of the assigned producer, Val Lewton, who moved on from RKO before production began. During the shoot, the script was constantly amended, partly to address objections from the Production Code Administration. There was a disastrous August 1946 preview in Santa Barbara, followed by series of new edits that were screened for, among other people, Mark Robson and John Huston, who gave their input. Renoir went to work with a different writer, Frank Davis (both men were good friends of the independent producer and director Albert Lewin) and reworked and/or re-shot somewhere between one third and one half of the film. The Woman on the Beach was finally delivered in April 1947. “Renoir managed to maintain a consistent perspective despite everything,” writes Bergstrom, “a consistency that came from paring down the elements of the film in almost Langian style by the time it was finished.” What exactly does “Langian” mean? That Renoir’s solution to dealing with the multiple limitations imposed on him by the enforcers of the Code and all the “Helpful Creative Suggestions” he undoubtedly had to endure from RKO execs was to remove secondary characters and explanatory scenes, to pull out dialogue, and to make the film more and more abstract. Which is undoubtedly why certain images and scenes have not just lingered but expanded in my memory—Ryan’s nightmare of jumping from his destroyed ship, falling to the bottom of the sea and into the arms of his beloved…Ryan riding on horseback through the fog and discovering Bennett by a shipwreck… and the remarkable moment where Bennett and Bickford sit next to each other, by the fireplace, both looking off in different directions, drily ruminating on their wreck of a marriage. It’s a very special film, quite unlike anything else by Renoir, and finally quite unlike anything else, period.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

THE WOMAN ON THE BEACH (1947, d. Jean Renoir)

Restored by the Library of Congress and The Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

24 years ago, I was thumbing through a copy of Cahiers du Cinéma and came across an item on a low budget ($50,000 to be exact) first film called Xiao Wu by a young Chinese director named Jia Zhangke. I was intrigued, because the description of Xiao Wu seemed wholly different from the Fifth Generation films of Chen Kaige, Zhang Yimou, or even Tian Zhuangzhuang. The film made its way through the international film festival circuit, first appearing in Berlin, and then a year later in Nantes and Pusan and Vancouver, and then in 1999 at the San Francisco International Film Festival. I served on the jury that year and I enjoyed meeting Jia, who was officially represented by the estimable Peggy Chiao—I have a fond memory of taking a Vertigo tour, and Peggy correcting the guide’s translation of the Chinese characters outside Scottie’s apartment building. It’s nice to make friends with filmmakers, but the work of assessment is something else again. Xiao Wu was a rare experience: I’d been hearing that it was great, and it actually exceeded my expectations. The minimal but pointed narrative of a young pickpocket in Jia’s hometown of Fenyang on an aimless downward path seemed to emanate from the reality of the city itself, which becomes a living breathing entity. This is partly due to the tactility of Yu Lik-wai’s images, partly due to the immersive density of the soundtrack, and Jia’s extraordinary patience and attention to ongoing life, which he translates into cinema. Xiao Wu put me in mind of Godard’s films in the 60s and Altman’s in the 70s, an immediate response to the world in the process of evolving. Xiao Wu was restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, in close collaboration with Jia. I’m looking forward to revisiting the film myself. It was the gateway to a singular and often surprising career. The nature of Jia’s filmmaking has changed, but his commitment to documenting and dramatizing the ongoing changes in the common life of his country has remained steadfast.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

XIAO WU (1997, d. Jia Zhangke)

Restored by The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L'Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in collaboration with Jia Zhangke and in association with MK2. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

Margaret Bodde, From Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, Kicks Off the Lumière Festival’s Classic Film Market

Lise Pedersen

A non-profit organization dedicated to film preservation and the exhibition of restored and classic cinema, the Foundation has overseen the restoration of over 900 films to date. In her keynote address at the Lumière Festival’s Classic Film Market, Bodde explained how it came about.

“It was 1990 and Martin Scorsese and a group of his fellow filmmakers like Spielberg, Lucas, Coppola, Kubrick and Pollack were really agitated at the idea that the cinema they grew up loving was literally fading away.

“At the time, there was no home video market and the studios had not instituted a systematic approach to their collections. So they created the Film Foundation to build a bridge between studios and the non-profit archives to raise awareness and funds for film preservation projects.”

As time went on, the Film Foundation turned its attention to independent films too. “Films that are independently produced are quite vulnerable, they are not housed necessarily in an archive or a studio vault,” Bodde explained. “What’s amazing is that, as these films are brought back out, it revitalizes filmmakers – women, people of color – that weren’t given proper attention when they were made, like Nina Menkes’ ‘The Bloody Child’ (1996) or ‘The Juniper Tree’ (1990) by Nietzchka Keene,” she went on.

In addition, the Foundation also works on experimental and avant-garde films through an annual grant, which has helped restore works by the likes of Andy Warhol, Jonas Mekas or Barbara Hammer. “If indie films are at risk of being lost, avant-garde, experimental films are orders of magnitude beyond that,” said Bodde.

The dialogue is ongoing between the Foundation and the film archives, which are invited to submit projects to the Foundation’s board once a year – a selection is made by the board based on criteria such as historical and cultural relevance, the film’s condition and its estimated restoration budget.

“The archives are our allies,” she said. “The studios are more challenging. They are not moved by morality, they are moved by economy, so you have to see what’s in their best interest.

“There has to be a recognition on the part of the studios that there is value to the library. At the moment, everyone is looking for that horrible word: ‘content’ – things they can monetize – and the library would be one of those. So you appeal to the fact that there is an audience for everything.”

In 2007, the Film Foundation decided to extend its reach beyond the U.S. with its World Cinema Project (WCP), launched in collaboration with its long-time partner Cineteca di Bologna, and a decade later the African Film Heritage Project was born. To date, 46 films have been restored under the WCP.

“The WCP is unique because once at-risk films are identified and restored, and the program takes on available distribution rights. Often, the films have only been seen in their country of origin, and we help bring them out and they become these discoveries,” said Bodde, who brought clips of one such film, the recently restored Iranian cult movie “Chess of the Wind” (1976) by Mohammad Reza Aslani.

Confiscated during the Islamic Revolution it was believed to be lost. Rediscovered in 2014, it was smuggled to Paris for restoration. The film has toured the festival circuit and is distributed globally by Foundation partners like France’s leading heritage film distributor Carlotta and Criterion in the U.S., which has released several DVD boxsets of WCP movies. It is partnerships like these that give restored films a second lease of life, said Bodde.

“As one newspaper said: It’s like walking around with a film festival in your bag,” she joked. “To put these films into context the way Criterion does so well, with essays and background and notes about the restoration, is fantastic,” she enthused. “These partnerships help the films reach a wider audience: they fill in a lot of gaps and shift our understanding of film culture.”

Asked about the future and the ever-growing changes in film consumption, accelerated by the pandemic, Bodde said: “We’ll keep doing what we do. The technology changes – it changed in 1927 with sound and then color! How we look at film’s changes: we stream things. I can watch a film on my phone if I so choose. But the films still have the same power – I mean not on my phone, I don’t think,” she joked. “But they are still communicating and inspiring, so we’ll keep that as our guiding light.”

The MIFC runs alongside the Lumière Film Festival in Lyon until Oct. 15.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

Tom Quinn, the founder and head of Neon, is taking a bold and necessary step forward in the name of cinema. Neon will be releasing Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Memoria as a “road show”—going one theatre in one city at a time across the country…and that’s it. No Blu-ray, no DVD, and most importantly of all: no streaming. No, Memoria will not be sharing a “swimlane” with (imagine algorhythmically generated “similar” films here). You will have to see it in a theatre, or miss it.

Will the film eventually turn up on some other platform? Possibly. But the gesture is very important.

In his resplendent Charles Eliot Norton lectures on the “crisis” of music in the 20th century, Leonard Bernstein posed the rhetorical question: does this focus on music and its development actually matter? Is it relevant? “The world totters,” said Bernstein, “governments crumble, and we are poring over musical phonology and syntax. Isn’t it a flagrant case of elitism? Well, in a way it is. Certainly not elitism of class—economic, social or ethnic—but of curiosity, that special inquiring quality of the intelligence. And it was ever thus. But these days, the search for meaning through beauty and visa-versa becomes even more important, as each day mediocrity and art-mongering increasingly uglify our lives. And the day when this search for John Keats’ truth/beauty ideal become irrelevant, then we can all shut up and go back to our caves. Meanwhile, to use that unfortunate word again, it is thoroughly relevant.”

These lectures were delivered almost 50 years ago. They could have been written yesterday.

We have arrived at a strange moment. The terms “elitism” and “elites” have been rendered so elastic as to become all but meaningless, and the same could be said of “friend,” “community,” “freedom” and “democratic.” And, of course, “social.” Market-driven logic is sold, relentlessly, as “reality.” And in the process, art is treated as a doormat, a tabula rasa on which one can project any half-baked “idea” or program. And the artists? Or the people who give themselves to art? Who pronounce the word cinema without shame, but with real pride? I can say from personal experience that the labels come fast and furious at the mere mention of the word. My own favorite was “effete,” a word that good old Spiro Agnew used to flog from the podium.

The reality of the market is not reality, period: there is an infinity of dimensions to being alive, and art is a precious reminder of just that. It is the polar antithesis of commerce, and it addresses us not as a consumer but as a fellow human being. That goes for every single title that’s been restored and preserved by The Film Foundation since its inception, including the 2000 title Mysterious Object at Noon, the first feature from Apichatpong Weerasethakul, known to many as Joe.

It’s wonderful that so much is available now, to see at home. The trade-off is that it is offered to us in the basest possible manner, determined by a bottom-line, lowest-common-denominator approach to programming, equalizing absolutely every moving image under the sun, and all but encouraging the consumer to bail the minute they get bored or distracted or confused or challenged or anything but lulled by more of the same. Again.

Films should be widely available. They should also be valued. That was why John Cassavetes made it so difficult to see his films when he was alive, and that is the point of Joe and Tom’s grand gesture.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

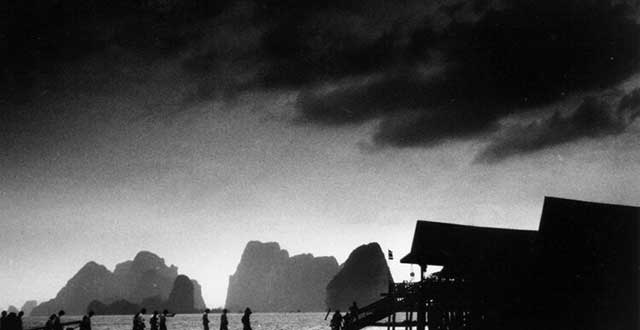

MYSTERIOUS OBJECT AT NOON (Thailand, 2000. d. Apichatpong Weerasethaku)

Restored in 2013 by the Austrian Film Museum and Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, LISTO laboratory in Vienna, Technicolor Ltd in Bangkok, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.