News

18 restored film gems to play at SIFF 2015

Moira Macdonald, The Seattle Times

Newly restored prints of “Rebel Without a Cause,” “The Apu Trilogy” and other classics will be shown at this year’s festival, in part due to the protective efforts of the Film Foundation.

“Why preserve?” asked filmmaker Martin Scorsese, in a 2013 lecture presented by the National Endowment for the Humanities. “Because we can’t know where we’re going unless we know where we’ve been — we can’t understand the future or the present until we have some sort of grappling with the past.”

Those thoughts led Scorsese, in 1990, to unite a group of filmmakers to form the Film Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting and preserving motion picture history. Twenty-five years later, the Film Foundation has helped to restore more than 600 rapidly deteriorating films, many of them classics. (“The Tales of Hoffmann,” which screened at Cinerama last month, was beautifully restored through the Film Foundation.) The Seattle International Film Festival will be showcasing a number of Film Foundation restorations in the next three weeks, in tribute to their organization’s pioneering work.

Margaret Bodde, the Film Foundation’s executive director, said last week that in 1990, an “urgent emergency” existed in the field of film preservation — archives, which held copies of rapidly degrading historic movies on nitrate film, lacked the funds and support to transfer them to more stable film stock. The Foundation acted as a bridge between the archives and the studios, who quickly realized that the burgeoning home video market gave them an incentive to preserve and stabilize classic films.

“It was a happy coincidence — that market emerged, and it was really a very compelling rationale for preservation,” said Bodde. “We had the ideological outreach that we were doing, but I think without the economic incentive, we wouldn’t have been able to be as successful at raising awareness and getting as many films restored and preserved.”

Now, the Film Foundation’s growth has spread worldwide, with a new World Cinema Project that has restored 24 films from Mexico, South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Central and Southeast Asia. Among these films are acclaimed African filmmaker Ousmane Sembène’s 1968 first feature, “Black Girl,” which screens at SIFF June 1 — just after the restoration’s world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival.

“With ‘Black Girl,’ we actually found the original negative,” said Bodde. As with many historic films, the process was something of a treasure hunt — “it turned out that the elements were held at an archive [in France] and people hadn’t remembered that it had been deposited there.”

“Black Girl” underwent a 4K digital restoration — a process through which the original negative is scanned and converted to a computer file. “It picks up every grain of visual content, and it transfers that into the digital realm,” said Bodde, who explained that technicians are then able to color correct, fix torn frames, and erase scratches and dirt. Many of these processes can be automated, making the system much more efficient than cleaning frame-by-frame by hand. The end result can then be transferred back to 35mm film, or converted to a digital presentation suitable for movie theaters (known as DCP), with the original safely stored.

1955’s “Rebel With a Cause,” screening in tribute to the late screenwriter Stewart Stern, also underwent a recent restoration through the Film Foundation. Though some may be surprised that such a well-known film would require such work, Bodde explained that director Nicholas Ray was working with a limited budget at the time.

“It’s iconic now, and obviously it’s one of the great Hollywood films that people think of as epitomizing the studio system, but when ‘Rebel’ was made, it was a low-budget film,” she said, noting that Ray used Eastman color stock, which faded easily, rather than the more expensive three-strip Technicolor. “You also had the popularity of the film, which meant that they were making prints off that negative left and right. It’s a double-edged sword of popularity and preservation — when pictures were big hits, you have more damage to the film.”

Other Film Foundation restorations in the festival include the 1940s thrillers “Caught” and “The Dark Mirror,” and the rarely seen 1932 gothic horror movie “The Old Dark House,” from director James Whale (“Frankenstein”). All three of these will screen in 35mm — an increasingly rare event in this digital age.

Ultimately, the goal of the foundation is to preserve film history for new generations, many of whom may experience these works on small screens — but an opportunity to view a restored work in a theater, as it was intended to be seen, is a rare treat.

“It’s communal,” said Bodde, of moviegoing. “That’s not replaceable when you’re watching something in the comfort of your own home. There’s nothing like experiencing a film with an audience and hearing where they’re laughing and what they’re responding to and what you’re responding to. It’s different and shared, at the same time.”

Archival films at SIFF

Film Foundation titles:

“Alyam, Alyam” (Morocco, 1978): SIFF screening TBA.

“Black Girl” (Senegal, 1968): 7 p.m. June 1, Harvard Exit.

“Caught” (USA, 1948): 8 p.m. May 28, Uptown

“The Color of the Pomegranites” (Armenia, 1969): 7 p.m. May 20, Harvard Exit

“The Dark Mirror” (USA, 1946): 6 p.m. May 28, Uptown

“The Old Dark House” (USA, 1932): 7 p.m. May 18, Egyptian

“Rebel Without a Cause” (USA, 1955): 4 p.m. May 31, Egyptian

“The Red Shoes” (U.K., 1948): 12:30 p.m. May 16, Egyptian

http://www.seattletimes.com/entertainment/movies/18-restored-film-gems-to-play-at-siff-2015/

Gucci backs film restoration for special 68th Cannes Film Festival presentation

Gucci celebrates its continued commitment to the preservation and restoration of classic cinema, through its ten-year collaboration with Martin Scorsese's The Film Foundation. This year will see the Italian fashion house's collaborative work with the foundation, revive a restoration of Luchino Visconti's Rocco e i suoi fratelli, originally made in 1960, at the annual Cannes Film Festival as part of the festival's 'Cannes Classics' programme.

Gucci was inspired to make a multi-million dollar commitment to The Film Foundation for the restoration of iconic and innovative films, ten years ago, thanks to a shared interest and appreciation of creative visionaries. Artistic filmmakers such as John Cassavetes, Sergio Leone and Federico Fellini are favourites of the luxury heritage fashion house that appreciates the bold and daring artistry and genre-redefining works of these directors and others like them.

The restoration of Rocco e i suoi fratelli, will debut at the Cannes Film Festival on May 17 after an introduction from Benicio Del Toro, who is an avid supporter of the continued work of The Film Foundation and Gucci: "There are so many great films from the past that have inspired me and continue to inform and fuel my work. It's important to support the preservation of these films so that future generations can experience their power and artistry. And Visconti was certainly one of the great cinematic visionaries," says Del Toro.

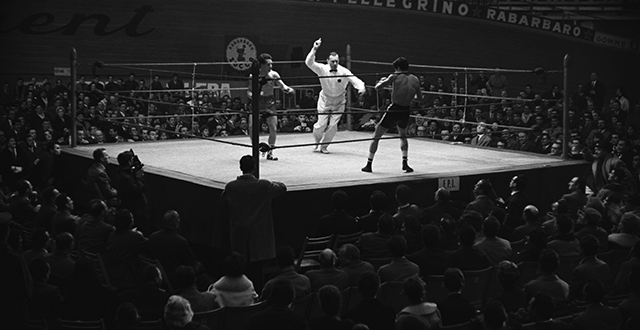

The 1960 film examines the effects that the industrial and economic boom (that was transforming Italy at that time,) had on the country, through following the eponimois Rocco and his brothers. It is the story of how this new world – represented by Milan city life –impacts a poor rural family. Martin Scorsese says: "Rocco is one of the most sumptuous black and white pictures I've ever seen: the images, shot by the great Giuseppe Rotunno, are pearly, elegant and lustrous – it's like a simultaneous continuation and development of neorealism. Thanks to Gucci and The Film Foundation and our friends at the Cineteca di Bologna, Luchino Visconti's masterpiece can be experienced once again in all its fearsome beauty and power."

Christopher Nolan Joins Film Foundation Board

Dave McNary, Variety

Christopher Nolan has joined the board of The Film Foundation, Martin Scorsese's non-profit film preservation organization.

Scorsese, the founder and chair of the organization, noted that Nolan has been a longtime advocate of sustaining celluloid film in the digital era.

“Chris’s passion, knowledge and dedication to film is unparalleled,” he said. “He spearheaded the growing movement to ensure that film stock continues to be available for production and preservation. I know that his commitment to film and its preservation will be enormously helpful to the work of the foundation.”

Nolan’s “Interstellar” opened first at 240 film-using theaters in the U.S. last November, two days prior to its wide release in theaters using digital projection. Nolan shot the movie with a combination of 35mm anamorphic film and 65mm Imax.

“I’m honored to become a part of the pioneering and essential work of Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation,” Nolan said. “The Foundation’s mission is more important today than ever before. I hope I can help with this vital effort.”

Current Film Foundation board members are Woody Allen, Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, Francis Ford Coppola, Clint Eastwood, Curtis Hanson, Peter Jackson, Ang Lee, George Lucas, Alexander Payne, Robert Redford and Steven Spielberg. The Film Foundation is also aligned with the Directors Guild of America.

“Christopher’s knowledge and advocacy for film preservation on behalf of filmmakers round out an impassioned board that has achieved such significant milestones throughout the years, and will assure that this critical work is carried into the future,” said DGA president Paris Barclay.

Martin Scorsese: my passion for the humour and panic of Polish cinema

Martin Scorsese, The Guardian

As for many other people, my introduction to Polish cinema came with Andrzej Wajda’s trilogy: Ashes and Diamonds, Kanal and A Generation – actually, they were released out of order here in the US, and we saw Kanal first, followed quickly by Ashes, both in 1961, and then we got to see A Generation later. Among the three, it was Ashes and Diamonds that had the greatest impact on me. It announced the arrival of a master film-maker. It was one of the last pictures that gave us a real testament of the impact of the war, on Wajda and on his nation. It introduced us to a whole school of film-making, related to what was coming out of the Soviet Union but quite distinct. And it gave us Zbigniew Cybulski, a great actor and a new generational icon.

But all Wajda’s films made an impression on me. Whenever I had the opportunity to see one I was impressed by his mastery. I also loved Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s films: Night Train, Mother Joan of the Angels and in particular Pharaoh, which had a fresh approach to the historical picture. Wojciec Has’s films, The Hourglass Sanatorium and later The Saragossa Manuscript, really astonished me. Andrzej Munk I caught up with a little later, plus, of course,Jerzy Skolimowski and Roman Polanski’s early pictures. The 50s and 60s were a great time in Polish cinema. A great time in cinema, period.

With Polish cinema, what I especially respond to is the mixture of passion, meticulous craftsmanship, dynamic deep focal-length compositions, moral dilemmas and religious conflicts, often done with a very sharp sense of humour. Humour and tragedy are very close in Polish cinema.

Plus, the struggle against official censorship and government clampdowns gives Polish cinema that was made during the communist era a heightened urgency. You can feel it in the rhythm, the intensity, even in pictures that have no obvious political subject matter. Or, in pictures that take the then-contemporary political situation and transpose it to an earlier period. For instance, Danton by Wajda, which he made in France during the Solidarity period in the early 1980s. There’s a restlessness, an unease, a desperation, an existential panic.

Many Polish film-makers spent some time in exile. Polanski left very early. Skolimowski has gone back and forth during the years. They adapted very well to the circumstances, wherever they went. But such a condition goes way beyond Polish cinema. What would the history of American cinema have been without the flood of directors from Europe in the 1920s through the 40s? Fritz Lang, Erich von Stroheim, FW Murnau, Ernst Lubitsch, Robert Siodmak,Michael Curtiz, Jacques Feyder, Edgar G Ulmer, Fred Zinnemann, Julien Duvivier, Max Reinhardt, William Dieterle, Alfred Hitchcock, Max Ophüls, Jean Renoir, and on and on and on. Obviously, exile creates a very different perspective on the country in which you end up making films. Take Polanski’sChinatown. It’s impossible to imagine an American-born director making that picture. You can imagine a version of it, but not the finished film we know as Chinatown.

This unique perspective stretches even to the movie posters. I own quite a few myself. They can seem odd to non-Polish viewers. Sometimes you look at them and wonder: what bearing does this image have on this picture? And then you see that there’s a rare place for cinema in the culture itself, because the relationship between the films and their posters is so unique. Most often, they capture the concept of the film itself.

Martin Scorsese Presents: Masterpieces of Polish Cinemaruns at BFI Southbank and Edinburgh Filmhouse until the end of May as part of the Kinoteka Polish film festival and then tours UK venues