News

NYFF: Martin Scorsese on Film Preservation

Film Comment

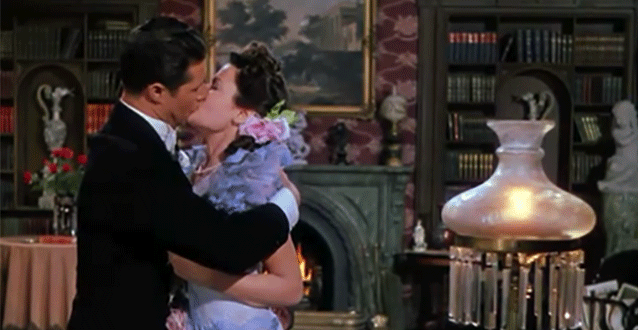

The 53rd New York Film Festival kicked off its showcase of revivals with Ernst Lubitsch’s magnificent Technicolor comedyHeaven Can Wait in a gorgeous restoration by 20th Century Fox in collaboration with the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation. Afterward, Martin Scorsese, founder and chair of The Film Foundation, was on hand to recall the early challenges in persuading studios of the need to preserve their films. His interlocutor at Alice Tully Hall was Director of the New York Film Festival Kent Jones, whose own tribute to filmmakers and film history, Hitchcock/Truffaut, previews tonight at the Film Society of Lincoln Center alongside a program of Hitchcock films, in advance of its release on December 2.

KENT JONES: It’s your first time in the new Alice Tully Hall.

MARTIN SCORSESE: It’s my first time in the new Alice Tully, because the other [Film Foundation] events have been at the Walter Reade for the past few years.

KJ: We were just talking backstage and I realized that Heaven Can Wait and Brooklyn, a Fox Searchlight picture, are both on 35mm. I wanted to start with the beginning, which is when you first realized the need for restoration and preservation actually had to exist. It was at a screening in L.A., right?

MS: Yes. It was at LACMA, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. I always imagined the room to be this big, but it was much smaller. They would have these wonderful programs back in the early Seventies, and one of the big ones was 20th Century Fox. They had restored a number of films—Sunrise, Blood Money,Seventh Heaven, the Rowland Brown pictures, about four or five of them. And they showed all the prints from the Fox vaults at the program.

KJ: So it all begins with Fox.

MS: Yes. I saw this film [Heaven Can Wait] in the original studio nitrate print. If you see nitrate on a big screen, there is a difference from “safety film.” This goes off the subject a bit, but I was talking about projecting a certain classic film off of a Blu-ray on a big screen for young people who are 13 or 14 years old. The impact, if it has any, is still the same, but it’s not a film experience. It’s a different kind of experience, and I think it’s akin to the difference between nitrate film and the celluloid that we’ve known for the past 50 years or so.

So we’d go on weekends—Jay Cox was with me, Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, a number of people—and they were showing everything from the silent films to the Fifties ’Scope pictures. And the black-and-white nitrate was amazing. This was right before I made Mean Streets in 1973. Around the same time I was living in Los Angeles, trying to see classic films, and we really couldn’t find good copies. If we were at a studio—Steven was at Universal, I was working for a while as an editor at Warner Brothers—and I’d ask to screen a film, they’d show me a studio print or something. But we were aware it was difficult to see complete films, films that weren’t scratched, or where the color wasn’t messed up.

We had seen Wilson [44] in 35mm Technicolor nitrate, The Black Swan [42], Blood and Sand [41], all these extraordinary uses of Technicolor from the late Thirties as part of the LACMA program. Wings of the Morning [37], the first British one… We didn’t know the full extent of it until one of the nights at LACMA, they were showing Niagara and The Seven Year Itch. So we sit through Niagara, which is a beautiful Technicolor film noir. And then there was a break, and before the second film begins, Ron Haver—who was amazing and pulled this all together, this show—comes out and says that the print of The Seven Year Itch from the studio is faded. This is 1972, or ’71. The Seven Year Itch was made in ’55. What made this so dramatic is that Niagara was made a couple of years before in ’53. When Fox got their first anamorphic lenses, every film, black and white or in color, they all had to be made in ‘Scope. And the color system was changed from a three-strip to a Monopack. So Ron Haver comes out, tells the audience that it’s a little faded, and everybody groaned. We had missed some other ’Scope films during the week that didn’t live up to their original glory, so to speak, and apparently the audience was quite aware of this. Then Ron said, “Listen. What’s going to happen is that we’re going to put a filter—” and people started yelling “No, no! Don’t put the filter back on! It goes out of focus! Please!” They were trying to correct the color by putting gels in front of the lens that would melt and make it go out of focus. So I said: “What the hell is going on?” The film starts, and it’s pink and blue. The whole thing! Beautiful stereophonic sound. Whatever you may think of Billy Wilder’s film, the Axelrod thing, the color, high Fifties, we’re talking an iconic film…We were so disappointed—our eyes were treated to this extraordinary Technicolor of Niagara and the films that had preceded it, and this was like falling off a cliff.

It was such a shock. We began to realize that everything since the Monopack was like this. This was the studio print. How did it get like this? It’s only been a few years! You couldn’t see the features of the actors anymore. You could, but it isn’t the same as seeing their faces in the lighting style of the Classical Hollywood era, either black and white or color. You couldn’t see what you were supposed to see. On top of that, you’re dealing with icons of cinema: Marilyn Monroe, a film that—

KJ: —Tom Ewell.

MS: Well, Tom Ewell no, but this is American theater, translated to screen. You’re missing the narrative, you’re missing the performance. Something is wrong with the image. So then they put the gels on, and it started to get soft, and people started to stamp their feet and get really mad, and that’s when we said “Let’s get out of here.” And we walked out. There were about five of us, and we were like: “What the hell? How can this be?” We’d seen bad copies of films on television, but not in a museum, not such a dramatic change. I saw House of Bamboo[55] at the studio: terrific stereophonic sound but the image was distanced and aged in a way. Long story, it goes on like this because we tried to find prints of films by 1975, ’76, and—oh, even The Leopard [63]! It was difficult to get a print to see that was in good condition of this film. The American version was two and a half hours or so, but even that was gone, so we got a 16mm print, but that was magenta.

I remember when we inquired further, Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma too, they said that we can’t keep all these prints around. I’m not talking about the studio prints, but at that point we realized the future of what had been created up until 1950 or 1960, that if nobody was made aware of it, it really came down to people going into the vaults and going through the cans. And that’s hard to do, because the people who are employed that way, they’re there to make sure that if they’re sent down there, they can find something—and that’s about it. But when they open these cans and look at them, for example, there was no system. Also around that time, in 1970, MGM went under and the films went somewhere else. Paramount had sold all of their pre-1948 films to Universal before video came out, thinking that there were no more legs in them, that they couldn’t make any money from them. There was an idea that film libraries were something that you had to get rid of. There were stories of negatives being burnt and thrown away.

KJ: And negatives that had been run into the ground, that had been used again and again.

MS: Particularly for very famous films. They began making more prints off of the original negative, over and over again, because there was a demand for it, and that disintegrated the negative.Rope [48] was that way, but it’s been restored by Fox. A lot of the prints were often original neg on that. But it was one of those things we began to realize: that the studios were in flux, that things were changing. There was no time for people to think what films are, what they were, what they can be, and what they are to a new generation. We got a bad rap in a way because we were young kids in our late twenties or so, and they thought we had to go to school to learn films. Some of the older guys working out there would say: “We didn’t have to school to learn how to make a film.” I’d say: “No, it’s not that you have to go to school to make a film. We’re very lucky to be involved with certain professors.” We got our hands on some equipment—but that’s New York. There was very little independent filmmaking in New York. Not enough, I should say. There was an impact—Cassavetes, Shirley Clarke, all the avant-garde cinema. There was an impact. But one wasn’t fed into the industry if you wanted to go that way. And I knew that narrative cinema was my thing.

KJ: You guys were the upstarts.

MS: Yeah, we were. They kept saying: “Well, what do you want to see these films for?” And we kept pushing them for making new prints. And the man who came in and made the biggest buyout was Ted Turner, getting all those films from Warner Brothers.

KJ: Who everybody thought was a villain at first because of colorization.

MS: Yes. Well, there was a battle there with colorization because there was that line: “Last time I looked, I owned it, and I’m going to do what I’m going to do.” And then it was a conflict about the value of the work of art. How can it be a work of art if it’s a commercial thing? Hmm. [Pauses] Let’s think about that. No! It means a lot to people. It’s inspired artists, novelists, poets, and painters, not just people who simply enjoy making narrative on film. It was really a mindset that had to be changed.

By 1979, I had really had it, and I couldn’t find anything that was in any good shape, and I decided to make Raging Bull in black and white. Also because there were about four other boxing films coming out that year: The Main Event, Rocky 2, andMatilda, the boxing kangaroo. [Audience erupts in laughter] Well, the Australians were a big deal with Mad Max… So what’s gonna be the difference? You’ve got a nice comedy, you got the Rocky thing, you got a kangaroo. But the red gloves? What isthat? We’re gonna be killed! Let’s just do it black and white. The studio was originally not for it, but we eventually got that done.

I was so angry about [color stock fading], the only thing I could do was to send an angry letter out about the fact that now every film has to be made in film at the studios, and if everything has to be made in color, that’s when the color gets cheaper. [As a director] you spend all that time designing in color—because whether it’s shades of browns and grays, you still have to design it, and then time it. It means something, the way you see things, and that’s just when the color’s not going to last. Just when you have to do it, that’s when it’s going to be bad. The time where it did last, which was the old Technicolor, it was considered mainly for musicals and comedies and Westerns, that sort of thing. I said that you can’t work when one of your major tools is being destroyed, and we have to do something to get a better color stock. So I attacked Eastman Kodak and sent out letters around the world to the filmmakers asking them to sign this petition to get a stronger, stable printing stock. There were many signatures, everyone from Ingmar Bergman to Kenneth Anger. Everyone signed it except Bob Altman. Bob Altman said that it’s not the film manufacturer, it’s the distributor. And I think he’s right. Afterward he became part of The Film Foundation, and he understood. But it was okay—we had to go after something, and I brought this idea of the color fading.

Then I began to realize, if that’s what you think about our culture, then there’s nothing in the culture. It’s a culture that you use up and throw away. You don’t care about it. If everybody’s walking around thinking that film changed their life, that a book changed their life, thinking that it’s going to be there all the time, to keep a continuity with the younger generations of this thing… If you think art is important at all, whether it’s commercial art or not, it seems to me it’s art. Maybe some are better than others. If it’s good, bad, or indifferent. It’s still art and we all know it’s very, very hard to even make a bad film.

KJ: Yeah…

[Audience laughs]

MS: Very hard. But if it comes out really bad, that’s why. With all of that effort and all of that love that was put into something—in most cases—and it means something to people, if the idea was just to show it only for a little while and then maybe show it cut up on TV, and then that’s it, what are we talking about in our culture? So I put together a program that I took around the world when we opened up Raging Bull and went on tour with it. We started with the trailers in color, one of them being Invaders from Mars [53], William Cameron Menzies’ film, very low-budget super Cinecolor film. And they were all laughing in the audience and I said: “What are you all laughing at? This is Close Encounters.” Those who know about the film I’m talking about, you know it’s the great William Cameron Menzies. There’s a new book coming out about him finally. You should see it and read it. Menzies is so important in production design.

This is one of the films that certain people saw at a certain age and it’s your cinema now—this is where it came from. So if you say “Invaders from Mars, who wants to keep it? Let it rot”? It’d change the industry! Funny, you know? Then I went into films by [Franz] Boas, North Native American tribal ritual dances, which were done in 1915, 1920. And then I showed a clip of a rocket going to the moon, NASA footage, I think. You see the rocket going in this glorious magenta. You made it to the moon, but the film was gone. It’s really interesting. What kind of thinking is this? And it was really a level of consciousness that we tried to change.

It was hard because Eastman Kodak said that we had to talk and they said, you know, this is not our thing. There is a stable stock: it costs a penny more a foot. And the studios at that time didn’t want to pay that. It’s not like now. If you’re going to send, what, 10,000 prints out or something, 4,000 prints, it’s a lot of money. But no one ever thought of it, to pay that extra penny a foot for the more stable stock. But that changed a lot. Everything changed, I think, by 1983-84. They made that stock available at no extra cost and that stock was called LPP at the time, and then it got better and it got much better and it continues to.

The point is that the film itself is no longer going to be around much longer. Yet we all know that the only stable element for preservation of film, even when you go through it digitally and you do your whole digital 4K, 6K, whatever it is. The only stable thing ultimately—you make separation masters and everything onto black and white— [is] celluloid, which supposedly lasts about a hundred years, 70 to 100 years.

KJ: A round of applause for celluloid.

MS: George Lucas was with me the other day, and we were talking and he says: “Yeah, it’ll last 10 years.” “Oh come on George, I’m telling you that celluloid…” He said: “If you’re doing a DI, you’re making a digital film.” I said: “I know, but still…” So we’re using film and digital at times.

KJ: The Film Foundation was formed in 1990 and over 600 films have been restored.

MS: The thing about The Film Foundation came out about the late 1980s… I tried to find films and restore the negatives by making new prints, and I would get permission from the studios to make new prints. The one that was the hardest was Pursued[47], Raoul Walsh’s Freudian Western. Once we got that, they couldn’t make a print of the original negative. And so Bob Rosen at UCLA at the time said: “Why don’t you take whatever color you guys have at this point and put it together and bring it to the studios and explain to them and see if you can create a little group.” And so with Mike Ovitz at CAA, we put together The Film Foundation. Sydney Pollack joined up, and Steven of course, and Lucas and Coppola.

KJ: And Altman.

MS: And then Altman came in, Robert Redford…

KJ: Clint Eastwood…

MS: Yeah. So what I did was while I was editing Goodfellas, I went through these books they call The MGM Story and The Warner Brothers Story, and they had every film that the studios made. And I tried to put them in order of, not importance, but a kind of necessity, whether it was a film I liked, I thought was overlooked and/or whether it’s a film that was Warner Brothers’ first two-strip Technicolor film. So I tried to put them in A, B, and C categories, and then I would get meetings with the heads of the studios with these books. They would let me in because I’d just done Goodfellas. I think it was one of those things where, you know: “He did Goodfellas and people like it but just… he has this thing. Just let him do his thing. Let him come in. Don’t make any kind of any fast moves.” You know what I’m saying? That kind of stuff. I remember it was Mickey Schulhof at Sony, because George Lucas went to the head of Sony at the time, Mr. Morita, and Mr. Morita said: “Michael Schulhof is the man, see him.”

So we got a meeting with him and when I gave him the book, he looked through it and he said: “You did this?” And I think what was very sweet about it is that he realized: “Yeah, they love these things. They love it.” He said, “You really went through all that?” It was every one of them. And then there was Bob Daly and Terry Semel, and Bob turning around to Warner Brothers and saying: “The problem is 20 years from now. What’s going to happen when we start doing the same thing?” That was the key to it. How is this going? Once you start with your photochemical restorations—digital was not around that clear at the time—but once you start that way, how is it going to change and how is it going to be? How is it going to be cared for and preserved?

The whole key of The Film Foundation was to unite the archives with the studios because, as I used to say, the studio was not only in production and distribution of a film, but it was production, distribution, and conservation. This art belongs to everyone. I said, you’re the custodians. That’s the idea. You have the great responsibility for preserving this work. Prior to that, the archives, from what I experienced, what I saw, were suspect, because they would find prints in garbage pails or whatever. But those films technically belonged to the studio, not the archives. And so in the worst-case scenario, they’re considered thieves. And it turns out—I remember it was the main head executive there at Universal years ago, when UCLA somehow restored For Whom The Bell Tolls from Universal Pictures, and Technicolor wanted to screen it at one of the theaters at UCLA, and they were stopped by the heads of the studio because they said: “It’s our picture. What are they doing? We own it.” But then they got involved too. Steven Spielberg went to Lew Wasserman and talked to him about it to try to change the thinking.

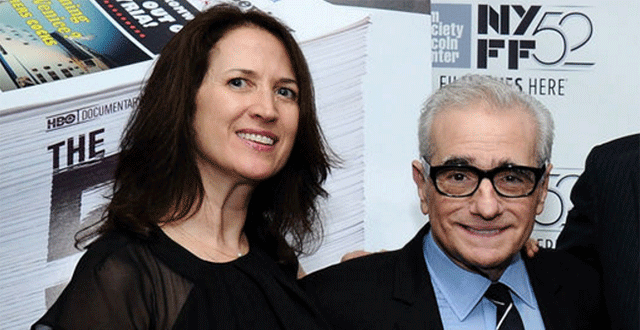

That’s a very different kind of thinking, you know. And at the same time, video started, and it was enormous. Then they realized that there’s no such thing [as] “an old film is just a film,” but, as Peter Bogdanovich said, “there’s also film that you’ve never seen.” That’s all. Kids know the difference to a certain extent with black and white, and even then if they show them in the right circumstances, it doesn’t matter after a few minutes. Anyway, that’s the general idea. Margaret Bodde and Jennifer Ahn…

KJ: Give them a round of applause.

MS: They were raising a lot of funding, an extraordinary amount. And one of the key things was that at the time we were told: “Don’t go into funding because it’s going to hurt possible funding for the archives from other places.” But I said, no, I think it’s something we could override if there was any kind of contention amongst the archives. At that time there were five, and now it’s seven. “If there’s any difficulty, we can override that. We’re talking about cinema. We’re talking about the film itself.”

KJ: Yeah. I think that that’s been overcome. Also, consciousness of film preservation has changed now. You mentioned something before, as we close, because we’re getting the high sign here—

MS: I’m sorry. It’s a long story. It’s 25 years, as it turns out.

KJ: I just want to close by saying that you know we’re celebrating the two anniversaries and the Fox anniversary, [and] just to say that you mentioned the idea of the studios being great custodians. This is the Fox story.

MS: Amazing. Every film, everything on the shelves. And all of that talk of the faded prints, forget it. This is the best. It’s amazing. I never thought I’d experience it, honestly.

KJ: I know, and that’s where it started. Thanks, Marty.

MS: Thank you, everybody.

The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project: Restoration Film Schools

Created in 1990 by Martin Scorsese, The Film Foundation (TFF) is dedicated to protecting and preserving motion picture history. By working in partnership with archives and studios, the Foundation preserves and restores cinematic treasures – nearly 700 to date – and makes these films available to international festivals and institutions. The Foundation’s World Cinema Project was created to restore, preserve and distribute neglected films from around the world. To date, 24 films from Mexico, South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Central and Southeast Asia have been made available to a global audience.

TFF is also teaching young people about film language and history through The Story of Movies, its innovative educational curriculum used by over 100,000 educators nationwide. Joining Scorsese on the board of directors are Woody Allen, Paul Thomas Anderson, Wes Anderson, Francis Ford Coppola, Clint Eastwood, Curtis Hanson, Peter Jackson, Ang Lee, George Lucas, Christopher Nolan, Alexander Payne, Robert Redford and Steven Spielberg. The Film Foundation is aligned with the Directors Guild of America – a key partner whose President and Secretary Treasurer also serve on the Foundation’s board.

Martin Scorsese’s vision – now in its 25th year – is to protect and preserve motion picture history. Recently, the Foundation expanded its scope to include the preservation, restoration and distribution of neglected films from around the world under the World Cinema Project.

As part of this new programme, the Foundation, in partnership with the Cineteca di Bologna and L’Immagine Ritrovata, hosts Film Restoration Schools to provide hands-on training to students and archivists in under-served regions. The first was organised with the National Museum of Singapore in November 2013 and attended by 40 students, selected from over 150 applicants from Hong Kong, Malaysia, Indonesia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand.

The Southeast Asia-Pacific Audio Visual Archive Association (SEAPAVAA) and a number of other Asian film archives and technical sponsors provided state-of-the-art equipment. The enthusiastic response to this first Restoration School strengthened the network of archivists, lab technicians, and educators in this region who are dedicated to continuing these important preservation and restoration initiatives.

This past February, TFF’s World Cinema Project, the Cineteca di Bologna and L’Immagine Ritrovata partnered with India’s Film Heritage Foundation, founded by award-winning filmmaker and preservation advocate, Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, for a Film Preservation and Restoration School in Mumbai. Throughout this week-long intensive course, students attended workshops covering each step of a film restoration workflow. Lectures and panel discussions included:

- A case study by Paramount’s Andrea Kalas

- Kieron Webb discussed the BFI’s restoration of Hitchcock’s nine surviving silent films

- Lee Kline discussed Criterion’s restoration process of the Apu Trilogy.

These workshops, classes, lectures and screenings represent a significant step towards raising awareness and teaching the best modern preservation practices in India, where there is limited access to hands-on experience and modern lab equipment.

This summer, TFF’s World Cinema Project provided support for NYU’s Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program (MIAP) as they continued their ongoing Audiovisual Preservation Exchange (APEX), returning to Buenos Aires to work with the Museo del Cine. Led by MIAP students Lorena Ramírez-López and Allison Whalen, the group of 14 volunteered two weeks of their time to work alongside film archivists at the Museo. The team included NYU MIAP students, alumni, faculty, and staff, as well as other professional archivists from the United States and Latin America. The APEX group in Argentina helped to inspect, catalogue, and process material, working on three of the museum’s film collections. The trip concluded with a day-long colloquium, Media Archiving in Latin America, attended by more than 50 other archivists and scholars who came from across Argentina, Uruguay, and Bolivia.

TFF’s World Cinema Project continues to expand its educational initiatives, for more information and updates on this and the foundation’s other preservation, education, and screening programmes, visit www.film-foundation.org.

La Film Foundation, mémoire du cinéma

Thomas Sotinel

A Lyon, tout au long du Festival Lumière, qui s’est achevé le 18 octobre, les films semblaient la plupart du temps parfaits : dans Marius, Raimu et Pierre Fresnay arboraient des mines resplendissantes ; dans David Golder, de Julien Duvivier, tourné comme le précédent en 1931, la voix d’Harry Baur résonnait et gémissait comme s’il était dans la pièce. Les couleurs de La Momie, de l’Egyptien Shadi Abdel Salam, éblouissaient comme elles avaient ébloui le grand cinéaste britannique Michael Powell, à la sortie du film, en 1969.

Cette perfection ne va pas de soi, et le festival a drainé, outre ses dizaines de milliers de spectateurs, presque tout ce que la planète compte de professionnels qui se vouent à la préservation et à la diffusion du patrimoine cinématographique : directeurs de cinémathèque, archivistes, historiens, restaurateurs… Au premier rang desquels l’équipe de la Film Foundation, créée par Martin Scorsese en 1990. C’est la Film Foundation qui a restauré La Momie, tout comme Colonel Blimp, de Michael Powell (1943), ou Larmes de clown, du Suédois Victor Sjöstrom (1924). Le but n’étant pas de constituer un fonds autonome mais d’enrichir les cinémathèques du monde entier.

Margaret Bodde, l’une des proches collaboratrices de Martin Scorsese (elle a produit nombre de ses documentaires) supervise le travail de la fondation, dont le conseil d’administration est constitué de réalisateurs – contemporains et cadets du fondateur, George Lucas et Alexander Payne, Steven Spielberg et Wes Anderson…

L’irruption du numérique

Il y a un quart de siècle, il s’agissait de sauver les films américains de la dégradation des supports, film nitrate en voie de désintégration ou film couleur qui prenait des libertés avec la réalité. « Depuis, la plupart des studios ont intensifié leurs efforts de préservation, observe Margaret Bodde, mais leurs collections sont si massives qu’il leur est impossible de tout garder. » C’est le travail du fondateur et des administrateurs que de sélectionner les films qu’il faut secourir. « Marty [Martin Scorsese] fait preuve d’une intuition troublante quant aux dangers qui peuvent menacer un film, explique-t-elle, il nous dit : “Il faudrait voir où en est Trafic en haute mer” [de Michael Curtiz, avec John Garfield, 1950]et, de fait, lorsque nous contactons l’UCLA [l’université de Los Angeles], qui détient le matériel, ils nous disent que l’affaire est urgente. »

Le travail en direction des cinématographies d’Afrique, d’Asie ou d’Amérique latine est du ressort du World Film Project, désormais intégré à la fondation. A Bologne, où elle travaille avec le laboratoire l’Immagine Ritrovata, Cecilia Cenciarelli centralise les demandes de restauration venues du monde entier et voyage ensuite à travers le monde – sa collègue Margaret Bodde la décrit comme « la James Bond du patrimoine cinématographique » pour démêler les questions de droits d’auteur ou pour convaincre les autorités de l’intérêt du projet.

L’exercice est d’autant plus difficile que l’irruption du numérique ne cesse de remettre en cause les techniques et les buts mêmes de la préservation.« Pendant cent ans, les fondements technologiques du cinéma sont restés les mêmes, explique Margaret Bodde, depuis l’apparition du numérique, ils ont changé au moins dix fois. »

C’est pourquoi on peut trouver sur le site de la Film Foundation une page destinée aux cinéastes débutants qui leur rappelle que « ce n’est pas parce que votre film est sur YouTube qu’il est préservé » et qui leur donne quelques conseils élémentaires : toujours conserver les éléments dans des formats non compressés, les changer de support au moins tous les trois ans… Parce que c’est aujourd’hui que se font les programmes des festivals de patrimoine du siècle prochain.

Diretor não quer só a cópia digital, diz Martin Scorsese

Guilherme Genestreti

O diretor Martin Scorsese, 72, será uma espécie de homenageado indireto da 39ª Mostra de Cinema de São Paulo, que começa em 22 de outubro.

Mas não conte com retrospectiva de longas como "Taxi Driver", "Touro Indomável" ou "Os Bons Companheiros". O festival paulistano presta homenagem ao lado restaurador desse cineasta lendário, que em 1990 criou a associação The Film Foundation, entidade que preserva filmes antigos.

A Mostra exibe 24 das mais de 700 obras restauradas pela instituição, entre elas "Como Era Verde o Meu Vale" (1941), de John Ford, e "Rashomon" (1950), de Akira Kurosawa.

Em entrevista à Folha, por e-mail, Scorsese faz um balanço dos 25 anos da organização que capitaneia ao lado de nomes como Steven Spielberg, Woody Allen e Francis Ford Coppola. Para ele, a revolução que substituiu as cópias em película no cinema traz uma dúvida: será que filmes capturados digitalmente poderão ser projetados no futuro, como as versões em 35 mm?

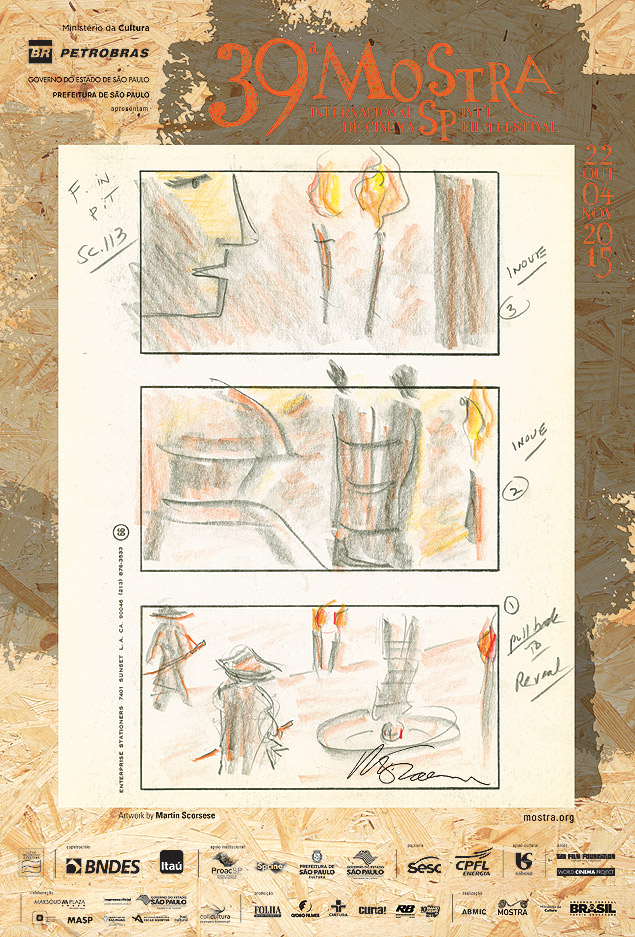

O cineasta também comentou o convite que recebeu para desenhar o pôster da Mostra. Para o cartaz, usou um storyboard de seu próximo filme, "Silence", previsto para 2016, sobre jesuítas portugueses perseguidos no Japão do século 17. Questionado sobre detalhes desse longa e aspectos de sua carreira, o diretor se manteve em silêncio.

Folha - O que descreve o storyboard de "Silence" que você selecionou upara criar o cartaz Mostra de São Paulo?

Martin Scorsese - O storyboard descreve uma cena crucial no filme e eu pensei que os desenhos funcionariam bem para o pôster. Tive a honra de ser convidado para isso.

| Martin Scorsese/Divulgação | ||

|

||

| Poster da 39ª Mostra de Cinema de São Paulo, com arte assinada pelo diretor Martin Scorsese |

Na sua opinião, a associação The Film Foundation foi capaz de realizar o seu propósito?

Há agora uma consciência disseminada sobre a importância do cinema e da preservação. E com a transição da película para o digital, há uma noção de que o filme é precioso.

Por quê?

Os cineastas não querem perder o filme como um meio e só ter a opção digital. Manter os filmes é absolutamente essencial na preservação deles. Sabemos que os filmes de mais de cem anos atrás ainda podem ser projetados. Seremos capazes de exibir um filme capturado digitalmente em 10 anos? Infelizmente não sabemos a resposta para essa pergunta. Ainda há muito trabalho a fazer para garantir que o trabalho criativo dos cineastas seja preservado para o futuro.

A Mostra planeja sessões especiais para exibir alguns desses filmes. Em sua opinião, qual é a importância de que novos públicos vejam esses clássicos na tela grande?

Gosto de pensar que não há algo coisa como filmes "antigos", mas filmes que alguns podem ainda não ter visto. Um filme é novo para uma plateia se eles nunca o viu antes. E a melhor maneira de vivenciar esse filme é pela forma como ele foi originalmente concebido para ser visto -na tela grande, com a melhor qualidade de imagem e compartilhado com o público. A missão da associação The Film Foundation é restaurar e preservar filmes –e já ajudou a salvar mais de 700 até agora. De igual importância é ter certeza de que esses filmes estão disponíveis para ser vistos pelo público. Todos os anos, centenas de exibições de filmes restaurados com financiamento da fundação são exibidos em locais em todo o mundo, em museus e festivais como esta apresentação emocionante em São Paulo.

Como é a escolha dos filmes que serão preservados?

A fundação ajuda a restaurar, em média, de 20 a 30 filmes por ano, trabalhando em parceria com arquivos de filmes de todo o mundo. Os projetos são propostos anualmente com base na necessidade mais urgente. Priorizar projetos é difícil, pois há muito mais do que podemos financiar. Ao decidir quais os filmes a restaurar, consideramos significado cultural e histórico, a condição física dos elementos e se eles são raros. Nós sempre tentamos trabalhar a partir dos negativos originais da câmera.

Você está envolvido na preservação de que filmes agora?

Atualmente, estamos trabalhando em vários projetos exclusivos, incluindo restaurar o corte original do diretor de "The Road Back" (1937), de James Whale, que tinha sido considerado um filme perdido por muitos; o documentário de quatro horas e meia "The Memory of Justice" (1976), de Marcel Ophüls "; e o drama mudo raramente visto "Rosita" (1923), de Ernst Lubitsch, estrelado por Mary Pickford. Estou pessoalmente envolvido em todas essas restaurações. Considero um privilégio ser capaz de ajudar a garantir que estes tesouros sejam restaurados e guardados para as gerações futuras.

O Brasil tem um filme restaurado pela fundação, "Limite" (1931), de Mário Peixoto. Por que decidiu preservar esse filme em particular?

"Limite" nunca foi lançado comercialmente e foi raramente visto no Brasil ou em qualquer outro lugar. Ao longo dos anos, alcançou uma espécie de status de lenda, especialmente por ter sido o único concluído pelo diretor Mário Peixoto, que tinha 21 anos quando o filme foi feito, em 1931. Tecnicamente inovador, de um expressionismo cheio de imaginação, profundamente poética ainda emocionalmente delicado, o filme é uma obra surpreendentemente madura e provocante, um feito verdadeiramente notável. Walter Salles tem sido um grande entusiasta deste filme e trabalhou durante anos em sua restauração, colaborando com Arquivo Mario Peixoto e seu curador, Saulo Pereira de Mello, bem como Carlos Magalhães e Patrícia de Filippi na Cinemateca Brasileira.

Há planos de restaurar outros brasileiros?

O Projeto Cinema Mundial [responsável pela restauração de títulos de todo o mundo], juntamente com Cineteca di Bologna e L'Immagine Ritrovata foi capaz de ajudar a garantir que esta obra-prima do cinema brasileiro ["Limite"] tivesse a preservação que merece. Esperamos ajudar mais filmes brasileiros.