News

SHORTLIST ANNOUNCED FOR FOCAL FOOTAGE AWARDS 2016

London, UK – 8th March 2016 - FOCAL International, the Federation of Commercial Audio-visual Libraries, today announced its shortlist for the thirteenth annual FOCAL International Awards, to be presented in association with AP Archive on 26th May 2016 at the Lancaster London Hotel, hosted by Kate Adie, the former Chief News Correspondent for the BBC and current presenter of From Our Own Correspondent on BBC Radio 4. The FOCAL International Awards celebrate the best use of footage across all variety of genres and media platforms, as well as those who preserve, restore and ensure that archival footage remains a vital resource to the global production community.

Sixteen awards will be presented in total, including the Lifetime Achievement Award, won this year by renowned film preservationist Robert Gitt.

This year’s finalists were drawn from a large, diverse and international pool of nominees, with a strong showing from the United States and Europe. The United States is also well represented in the Footage Researcher of the Year nominations and this was from a very strong field of 12 entries in that category.

“We are delighted with both the international turnout and the prevalence in this year’s shortlist of so many highly-acclaimed archive-based films such as Amy, Cobain and Best of Enemies,” said event organizer Julie Lewis.

The FOCAL International Awards also honour the work of archival researchers, footage archivists and film preservationists, with this year’s Lifetime achievement award going to legendary film preservationist Robert Gitt.In a career spanning more than fifty years, Robert Gitt has gained an international reputation as one of the foremost experts in the preservation and restoration of motion pictures. In addition, Gitt will deliver the Jane Mercer Memorial Lecture on May 24th in the lead up to the FOCAL International Awards ceremony.

Tickets for the Gala Awards Ceremony 26th May are now on sale, so you'll need to hurry if you want to book a table http://www.focalint.org/focal-international-awards

SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES: Please talk with ANNE JOHNSON at FOCAL International if you are interested info@focalint.org +44 (0)20 7663 8090

FINAL NOMINATIONS - FOCAL INTERNATIONAL AWARDS in association with AP ARCHIVE:

Best Use of Footage in a History Production

Sponsored by Getty Images / BBC Motion Gallery

• A German Youth (Une Jeunesse Allemande) – Local Films (France)

• Every Face Has a Name - Auto Images (Sweden)

• Red Gold (L'Or Rouge) - Vivement Lundi ! (France)

Best Use of Footage in a Current Affairs Production

Sponsored by Bloomberg Content Service

• Clockwork Climate - Artline Films (France)

• India's Daughter - Assassin Films (UK)

• The Queen of Ireland - Blinder Films (Ireland)

Best Use of Footage in a Factual Production

Sponsored by Bridgeman Footage

• Best of Enemies - Magnolia Pictures (USA)

• The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution - Firelight Films, Inc (USA)

• The Killing Fields of Dr. Haing S. Ngor - DeepFocus Productions, Inc (USA)

Best Use of Footage in an Entertainment Production

Sponsored by FremantleMedia Archive

• A City Dreaming - Indie Movie Company for BBC NI (UK)

• Best of Enemies - Tremolo Productions / Magnolia Pictures (USA)

• Children Over Time - RAI Radiotelevisione Italiana (Italy)

Best Use of Footage in an Arts Production

Sponsor sought

• Arena: Night and Day - BBC (UK)

• By Sidney Lumet - RatPac Documentary Films / Augusta Films / Thirteen Productions LLC's (USA)

• Imagine: The Ecstasy of Wilko Johnson - Essential Nitrate Limited / BBC (UK)

Best Use of Footage in a Music Production

Sponsored by Shutterstock

• Amy - On The Corner (UK)

• Cobain: Montage of Heck - End of Movie, LLC (USA)

• Eurovision at 60 - BBC Entertainment Production (UK)

Best Use of Sports Footage

Sponsored by ITV Sport Archive

• Building Jerusalem - New Black Films Limited (UK)

• Free to Run - Yuzu Productions (France) Point Prod (Switzerland) and Eklektik Productions (Belgium)

• I Believe In Miracles - Baby Cow Productions and Spool Films (UK)

Best Use of Footage in an Advert or Short Production

Sponsor sought

• Gatorade 'Heritage' - Stalkr/TBWA/Chiat/Day (USA)

• Lenor 'Odes to Clothes: Marvellous Scarf' - The Director Studio for Grey Düsseldorf (UK/Germany)

• MTV 'Tagline Here' - Stalkr/ Ghost Robot (USA)

Best use of Footage about the Natural World

Sponsor sought

• Beasts Behaving Badly - Barcroft Productions (UK)

• The Nature of Things: Jellyfish Rule! - CBC (Canada)

• Wild 24 - NHNZ / Nat Geo Wild (New Zealand)

Best Use of Footage on non-Television Platforms

Sponsor sought

• Bitter Lake - BBC Productions (UK)

• Britain on Film - BFI (UK)

• The Beatles 1+ Video Collection - Apple Corps Limited (UK)

Best Use of Footage in a Cinema Release

Sponsored by British Pathé

• Amy - On The Corner (UK)

• Cobain: Montage of Heck - End of Movie, LLC (USA)

• Free to Run - Yuzu Productions (France) Point Prod (Switzerland) and Eklektik Productions (Belgium)

Best Archive Restoration / Preservation Project or Title

Sponsor sought

• La Noire de... Restored by The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project in collaboration with the Sembene Estate, INA, Eclair Laboratories and Centre National de Cinematographie. Restoration carried out at Cineteca di Bologna - (USA/Italy)

• Marius – Compagnie Méditerranéenne de Films-MPC and the Cinémathèque française, with the support of the CNC, the Franco-American Cultural Fund DGA-MPA -SACEM-WGAW, the help of ARTE France Cinema Department, the Audiovisual Archives of Monaco, and the participation of SOGEDA Monaco / Digimage Classics (France)

• The Memory of Justice – The Film Foundation / Academy Film Archive (USA)

• Varieté - Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung and Filmarchiv Austria (Germany/Austria)

The Jane Mercer Footage Researcher of the Year Award

Sponsored by AP Archive

• Colleen Cavanaugh Anthony, Alexis Owens (Stalkr/USA) - Transparent Srs 2 Titles;

The Big Short; MTV Tagline Here

• Jessica Berman-Bogdan (USA) - Cobain: Montage of Heck; Narcos

• Prudence Arndt, Deborah Ford Gribaudi (USA/France) - Free To Run

Footage Employee of the Year

Sponsored by Creative Skillset

• Tim Emblem English (BBC Studios and Post Production)

• Paul Davis (Getty Images)

• Bhirel Wilson (BBC Motion Gallery / Getty Images)

Footage Library of the Year

Sponsored by Bonded Services

• Historic Films Archive

• Huntley Film Archives

• Kinolibrary

Lifetime Achievement Award

A gift of the FOCAL International Executive

Robert Gitt

To see the CREDITS and SYNOPSES of the final nominations and the full list of 191 submissions to the FOCAL International Awards from 17 countries click on the relevant category drop-down list through the hyperlinks above or via http://www.focalint.org/focal-international-awards/2016/the-focal-international-awards-2016

ABOUT FOCAL INTERNATIONAL

The Federation of Commercial Audiovisual Libraries International is a professional not-for-profit trade association formed in 1985. It is fully established as one of the leading voices in the industry, with a membership of over 300 international companies and individuals.

Its purpose is to facilitate the use of library footage, images, stills and audio in all forms of media production; promote its members - libraries selling content plus those whose serve the industry; provide a platform for members to promote themselves and their interests; encourage good practise in the research, licensing, copyright clearance and use of footage; support, promote and educate on the need to preserve and restore footage and content; act as an information resource for the footage and content industry; offer training in key skills and in the broader appreciation of the footage and content industry.

www.focalint.org

NFAI workshop to help preserve India’s cinematic heritage

Shoumojit Banerjee

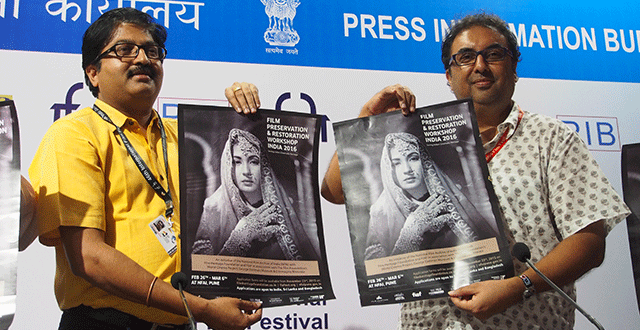

The National Film Archive of India, the country’s largest film archive and custodian of the Indian film heritage, is conducting a workshop in film preservation and restoration to help conserve the nation’s cinematic legacy.

The NFAI, in collaboration with the International Federation of Film Archives (FIAF) and the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF), will conduct a one-of-a-kind 10-day workshop beginning February 26 titled ‘Film preservation & restoration workshop India 2016’.

The objective of this programme is not only to augment the infrastructure and capacity of the NFAI but also to build an indigenous resource of film archivists and restorers who can work towards saving India’s cinematic heritage.

“There is no culture of ‘preserving’ in this country. The first week-long workshop held in Mumbai in the Films’ Division last year was a resounding success. Fortunately, the fact that film preservation is a specialised field and that we need to build an indigenous resource of trained archivists that can take this movement forward is a fact that is gradually impressing itself,” said Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, who heads the FHF, commenting on the genesis of the workshop.

The ten-day advanced course has been specially designed by David Walsh, head of the FIAF Technical Commission, with focus on intensive practical training in current film preservation and archival practices.

“Since Indian cinema has been gaining attention of researchers and scholars across the world, it becomes imperative that these aspects along with meta-data management be made ready as per universal standards,” Mr. Dungarpur said.

The workshop will be an advanced course with emphasis on documentation, cataloguing, projection system and the importance of preserving films in celluloid and digital.

Lectures and practical sessions in the workshop will be conducted by leading archivists and restorers from preeminent film institutions in the world such as the George Eastman Museum, Selznick School of Film Preservation, FIAF and L’Immagine Ritrovata, and is supported by Martin Scorsese’s ‘The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project’. There will be equal emphasis on preservation of heritage on celluloid format along with digitisation, said NFAI Director Prakash Magdum.

“Even though India is one of the largest producers of movies in the world, general awareness about film preservation is abysmal and is not looked as a career option. So, through this workshop, we will showcase the use of the latest technological advances that will prolong the life of celluloid film,” Mr Magdum said. The NFAI in recent years has carried out digitisation of nearly 500 films and the restoration of 300 more a few years back.

BERLINALE CLASSICS: PRESENTING SIX NEWLY-RESTORED FILMS FROM GERMANY, JAPAN, TAIWAN AND THE USA

Berlinale Classics

The Berlinale Classics series of the 66th Berlin International Film Festival will present premieres of six films, two German and four international productions, five of them world premieres.

Heiner Carow’s semi-autobiographical film Die Russen kommen (The Russians are Coming, GDR, 1968) is set in the waning days of World War II. For 16-year-old Günter Walcher, the defeat of the Nazis is a catastrophe that brings his world to collapse. But a film about fascism without anti-fascist heroes was a no-go for the East German regime, and the film was banned before completion. In 1987, it was reconstructed based on a severely damaged work print, as only small sections of the negative had survived. Digital technology has now enabled the DEFA Foundation, in cooperation with the German Federal Film Archive, to produce a new restoration by combining footage from disparate source elements that varied in optical quality.

The American film The Road Back directed by James Whale in 1937, also references a slice of German history. It is based on the eponymous Erich Maria Remarque novel about four German infantrymen who face a difficult road back to civilian life. In 1939, after protests from Germany, Universal Studios re-edited the film without consulting the director. The festival is showing a reconstruction of James Whale’s original 1937 theatrical release version, preserved by the Library of Congress in collaboration with NBCUniversal and Martin Scorsese's The Film Foundation. David Stenn and the UCLA Film & Television Archive provided skills and film footage.

“It’s particularly fascinating that two of the Berlinale Classics movies are closely linked to censorship in Germany's past", says Rainer Rother, section head for the Retrospective and artistic director of the Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek foundation. Heiner Carow’s The Russians are Coming is among the films that were banned or censored in East Germany for political reasons. We are showing several of those films in this year's Retrospective "Germany 1966. Redefining Cinema". Another illuminating example of the interference to which those films were subjected is The Road Back. It is proof that the political influence of the Nazi authorities was not restricted to Germany.“

With the digitally restored version of Bakushu (Early Summer), Berlinale Classics is once again presenting a work by Japanese master director Yasujiro Ozu. The 1951 film, about a young woman named Noriko whose family is trying to marry her off, is one of Ozu’s later works. Noriko is played by Ozu’s favourite actress, Setsuko Hara, who died in September 2015 at the age of 95. The 4K digital restoration project by the well-known Japanese production company Shochiku was led by Ozu’s former assistant cameraman Takashi Kawamata and cinematographer Masashi Chikamori, known for his work as a DP on Yoji Yamada films.

Also from Asia is the Taiwanese film Ni Luo He Nu Er (Daughter of the Nile) by Huo Hsiao-hsien, made in 1987. It is the director’s first film focusing on a female protagonist, and also notable for its depiction of Taipei in the 1980s. The digital restoration was based on the original 35 mm negative and was done under the aegis of the Taiwan Film Institute with Chen Huai-en, the film's cinematographer, overseeing the 4K-restoration.

Another digitally restored film from the US in the Berlinale Classics section is John Huston’s classic Fat City, made in 1972 with virtuoso cinematography by DP Conrad Hall. It features Jeff Bridges in one of his first screen roles, as the talented boxer Ernie. The melancholy tone of the film is set by Kris Kristofferson’s hit “Help Me Make It Through the Night". The film was restored from an original 35 mm negative and digitised in 4K by Sony Pictures, under the supervision of Grover Crisp.

The Berlinale Classics section will open with Fritz Lang’s 1921 silent film classic Der müde Tod(Destiny). The digitally restored version, made possible by the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation, will premiere on February 12, 2016 in the Friedrichstadtpalast Friedrichstadtpalast (see press release from Dec 2, 2015). Broadcasters ZDF / ARTE commissioned new music for the film from composer Cornelius Schwehr, which will be played by the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin (RSB), with conductor Frank Strobel at the podium.

Berlinale Classics programme

Bakushu (Early Summer)

By Yasujiro Ozu, Japan, 1951

Monday Feb. 15, 2016, CinemaxX 8

World premiere of the digitally restored version in 4K DCP

Fat City

By John Huston, USA, 1972

Friday Feb. 19, 2016, CinemaxX 8

International premiere of the digitally restored version in 4K DCP

Der müde Tod (Destiny)

By Fritz Lang, Germany, 1921

Friday Feb. 12, 2016, Friedrichstadtpalast

World premiere of the digitally restored version in 2K DCP

Music by the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin (RSB) conducted by Frank Strobel

Ni Luo He Nu Er (Daughter of the Nile)

By Hou Hsiao-hsien, Taiwan, 1987

Sunday Feb. 14, 2016, CinemaxX 8

World premiere of the digitally restored version in 4K DCP

The Road Back

By James Whale, USA, 1937

Tuesday Feb. 16, 2016, CinemaxX 8

World premiere of the restored version in 35mm

Die Russen kommen (The Russians are Coming)

By Heiner Carow, East Germany, 1968/1987

Saturday Feb. 13, 2016, CinemaxX 8

World premiere of the digitally restored version in 2K DCP

https://www.berlinale.de/en/presse/pressemitteilungen/retrospektive/retro-presse-detail_30933.html

Para que o passado sobreviva ao futuro

Daniel Oliveira

Parceira profissional de Martin Scorsese há 24 anos, Margaret Bodde foi a pessoa que o cineasta escolheu para confiar um de seus projetos mais importantes: a Film Foundation. No Brasil para receber uma homenagem na Mostra de Cinema de São Paulo pelos 25 anos da instituição, a sua atual diretora conversou com O TEMPO sobre a história e o funcionamento da fundação, e seus desafios em um mundo digital.

Queria que você começasse me contando um pouco da sua formação, e como você chegou ao cargo que possui hoje na Fundação.

Eu trabalho com Martin Scorsese há 24 anos, um ano a menos que a existência da Film Foundation. E uma das coisas de que ele gostou quando nos conhecemos e conversamos sobre trabalhar juntos era que eu tinha estudado cinema, conhecia a história do cinema, me interessava e me importava com ela. Meu primeiro emprego depois da faculdade foi na Library of Congress, cuidando do arquivo de filmes e fotografias, então eu tinha algum background em preservação. E eu também tinha trabalhado com distribuição independente, em uma das primeiras encarnações da Miramax. E o Marty gostou de que eu tivesse trabalhado para alguém tão duro e exigente como Harvey Weinstein. Ele achou que a combinação de todas essas habilidades funcionaria bem.

Então, você já começou na direção da Fundação?

Não. Eu comecei, na verdade, como assistente dele. Eu ajudava na produção dos filmes, e a preservação e a administração da Fundação eram parte do meu trabalho. Era algo em que eu ajudava quando tinha tempo. A gente ainda estava tentando entender o que a Fundação era, o que faria, como ajudaríamos. E em três ou quatro anos, Marty achou que os resultados que estávamos atingindo eram tão bons e importantes que me pediu para focar exclusivamente na Fundação. Ele arrumou outra assistente, eu fiquei com a parte de preservação e também produzi alguns documentários para ele.

E como a Fundação surge, e qual era seu objetivo inicial?

A Fundação foi originalmente criada por cineastas como Scorsese, Clint Eastwood, Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, George Lucas – eram cerca de nove, no total. Originalmente, ela deveria chamar atenção e levantar fundos para a preservação do cinema. E construir pontes entre os estúdios, com fins lucrativos, donos dos direitos dos filmes, e os arquivos, sem fins lucrativos, e que tinham grande parte dos negativos desses filmes. Porque não havia nenhum tipo de colaboração ou diálogo entre os dois, e esses fundadores queriam usar seu poder e autoridade para fazer com que esses dois elos trabalhassem juntos, com a Fundação no meio para financiar projetos que não fossem de propriedade dos estúdios ou que tivessem um maior caráter de urgência. E, claro, chamar a atenção do público em geral e da indústria para a importância de abrir os cofres, as caixas, olhar os negativos, ver se eles estão vinagrando, salvar aqueles que estão se deteriorando mais rápido. Então, a Fundação se tornou uma voz que a indústria e o público escutavam. Porque quando Martin Scorsese e Steven Spielberg estão falando, as pessoas querem ouvir. E isso era importante para eles – e para mim, também, porque eu amo cinema: usar a fama e a paixão que o público tem pelo trabalho deles como alicerce da Fundação.

Como ela funciona na prática?

Nós criamos um programa principal, que era a preservação e restauração de filmes, e essa era a essência da Fundação. Não começamos pensando em trabalhar apenas com o cinema norte-americano, só que acabamos iniciando por ele porque havia uma demanda tão grande. Mas nos primeiros anos, também atuamos no cinema indiano, com a obra de Satyajit Ray, porque o Arquivo da Academia estava trabalhando nos filmes dele. E eventualmente, migramos para o cinema inglês, italiano. Não muitos franceses porque a França toma ótimo cuidado de sua história cinematográfica. Também fomos para o Japão, onde restauramos “Rashomon”. E nos últimos anos, o Marty decidiu focar na cinematografia de países em desenvolvimento com o World Cinema Project, que se volta para lugares onde não existem arquivos nem infraestrutura para cuidar de sua história audiovisual. A gente vai até esses locais e conversa diretamente com os realizadores, ou seus herdeiros, filhos, netos ou os próprios produtores, e perguntamos se eles sabem onde estão as cópias. Às vezes é sim, outras não. Algumas é “no armário”. Daí, nós colaboramos com eles para que esses filmes, que são marcos na cinematografia de seus países, e do mundo, sejam restaurados, preservados – e distribuídos. Essa é a maior diferença do World Cinema Project: quando os direitos estão disponíveis, nós distribuímos o filme.

E qual é o maior desafio desse trabalho?

É a transição da película para o digital. Por 130 anos, o cinema consistia de uma mídia. E você pode pegar um rolo de filme de 100 anos, esticá-lo contra a luz e ver o que está gravado nele. Se você pegar uma fita beta e não tiver um reprodutor próprio, não vai saber o que tem ali. Então, é impossível saber se esse material vai sobreviver porque estamos vivendo uma transição muito rápida. É como se todos os pintores decidissem que as telas, tintas e óleos não servissem mais. E imediatamente, todo mundo tem que pintar na tela do computador. Sei que é uma analogia dramática. Mas essa decisão feita pela indústria, por questões de custo e distribuição, foi muito rápida e pode ter consequências que ninguém previu.

Como isso afeta o trabalho da Fundação?

Nós estamos alerta a essa questão. Porque a melhor forma de preservar um filme, mesmo que ele tenha sido feito digitalmente, ainda é a película. Idealmente, você ainda deve ter masters separadas em preto e branco que manterão seu trabalho vivo e acessível por muitos e muitos anos porque a evolução digital é tão rápida hoje que ninguém sabe se o formato padrão atual vai ser reproduzível em 50 anos. Mas à medida que a película se torna menos disponível e mais cara, espero que isso nunca aconteça, mas pode chegar um ponto em que ela não seja mais fabricada. E isso afeta a preservação diretamente. Porque vamos precisar confiar no digital para preservar filmes feitos no passado, em película, e não sabemos a vida útil dessas mídias. Sabemos algumas coisas que podem ajudar, como migrar o filme anualmente de um HD para outro – para que você tenha certeza de que o material ainda está ali. Mas ainda temos mais perguntas do que respostas no que tange a preservação, pelo menos até termos um formato digital estável que não mude a cada seis meses e se torne obsoleto e não-reproduzível cm cinco anos – daí, a importância da migração.

Mas se película é a melhor forma de preservação, é possível manter esse ideal com todos os laboratórios fechando no mundo todo?

Isso é uma crise. Revelar e reproduzir cópias não é um processo artesanal, algo que pode ser feito em uma escala pequena. A economia e a logística desse trabalho precisam ser feitas em escala industrial. Se alguém pensar em abrir um laboratório pequeno, para fazer 100 cópias por ano, eles vão à falência em um mês. Então, é um problema enorme e eu não sei qual é a resposta. Nos EUA, ainda há um bom laboratório em Nova York e dois em Los Angeles. Marty acabou de filmar seu último longa, “Silence”, em película e teve que mandar o material de Taiwan para o único laboratório em LA que ainda revela filme para produção.

Existe algum lugar hoje em que a preservação da memória cinematográfica está especialmente ameaçada, em que a intervenção é mais urgente?

Há vários. Mas um continente com o qual estamos particularmente preocupados é a África. Porque acabamos de fazer a restauração de “A Garota Negra”, de Ousmane Sembene, e ninguém sabia onde o negativo original estava. E ele é um marco, o “Cidadão Kane” da África. Se ele estava perdido, imagine os menos reconhecidos. Nós o encontramos, e o que o World Cinema Project quer é fazer isso para todas as principais cinematografias da África.

E o Brasil, como você avaliaria o estado da preservação cinematográfica aqui?

Gostaríamos de trabalhar em mais projetos brasileiros. Eu conversei com algumas pessoas da Cinemateca e queremos ajudá-los a identificar filmes especialmente necessitados de preservação. Acabamos de fazer o “Limite”, nosso primeiro trabalho brasileiro, mas um apenas não é o suficiente.

E o que mais surpreendeu você nesse trabalho desde que você começou há 24 anos?

Que eu ainda estou fazendo (risos). Porque a área da preservação evoluiu. E eu fico feliz em saber que a Fundação ainda existe, é relevante e serve um propósito na cultura cinematográfica.

E nesses 25 anos, houve algum projeto que tenha sido especial para você, como amante do cinema?

Um projeto recente de que eu estou extremamente orgulhosa é a restauração do documentário de cinco horas do Marcel Ophuls sobre Nuremberg, “The Memory of Justice”. Foi feito em 1976, e não foi visto desde então porque os direitos das imagens de arquivos e música haviam expirado. E a Fundação decidiu restaurá-lo e renovar os direitos para exibição em festivais e sessões não-comerciais. Foi um projeto de três a cinco anos especial para mim porque, quando alguém me diz “não é possível”, é quando eu realmente quero fazer. A Fundação tem o privilégio de ter o Marty e os outros diretores que nos permitem ir aonde outras pessoas não podem. E o que tornou esse projeto ainda mais especial é que o Marcel Ophuls ainda está vivo e pôde ir a vários festivais, então o filme dele ganhou uma segunda vida. E é um documentário profundamente relevante sobre várias questões que nos assolam ainda hoje.

Scorsese é um dos maiores cinéfilos do mundo, mas também um dos diretores mais importantes em atividade. O quanto ele ainda pode colaborar no trabalho da Fundação?

Muito. Desde sugerir títulos que precisam ser restaurados, que estão indisponíveis ou em risco, até levantar fundos e assistir aos testes de restaurações em progresso. E, quando o filme está pronto, ele é muito envolvido no processo de conversar com a mídia e o público sobre por que aquela obra é especial. Acabamos de exibir sete filmes restaurados pela Fundação no New York Film Festival, e Marty estava lá introduzindo cada um para seus conterrâneos e explicando para eles a sua importância.

Quais são os planos para os próximos 25 anos?

Nós criamos um programa educacional sobre a história do cinema, com uma disciplina para que alunos do ensino fundamental e médio nos EUA entendam a linguagem cinematográfica. Como histórias são contadas visualmente – o que um diretor faz, o que um diretor de fotografia contribui, o trabalho do roteirista. Ele introduz jovens à ideia de que há filmes antigos que são importantes e dos quais eles talvez gostem e que os enriqueçam culturalmente. “Eu me torno um espectador melhor e mais ativo, mesmo de filmes atuais, porque eu entendo a gramática do cinema. E quero preservar os filmes do passado porque sei o valor deles”. É um programa que está crescendo, e que eu gostaria de levar a outros países com suas cinematografias próprias. Isso é o que eu vejo no futuro: educação, acesso, exibição dos filmes em película – temos uma iniciativa para criar um espaço de exibição em película em Los Angeles.

O trabalho da Fundação existe porque diretores e produtores não pensaram em preservar seu trabalho há 100, 70, 50 anos. Você acha que os realizadores hoje estão mais conscientes dess importância?

Gosto de pensar que sim. Mas sinto que, porque o digital é tão fácil e tão disponível, talvez os cineastas não pensem muito na necessidade de preservar esse material. Só porque está no Youtube ou no HD do seu computador não significa que está seguro. Seu computador pode morrer, seu notebook pode ser roubado. Você deve ter múltiplas cópias, com arquivos descomprimidos, em mais de um lugar. Essa é uma mensagem que ainda precisa ser divulgada, e a Fundação está trabalhando para que ela seja ouvida pelos realizadores.