News

Al Festival del muto «La Czarina»: rivive la regina erotica di Lubitsch

Paolo Mereghetti

Il film in gran parte distrutto dopo il 1924, ora è stato ricostruito quasi integralmente

Un Lubitsch mai visto è uno dei tanti regali di questa trentasettesima edizione delle Giornate del cinema muto di Pordenone. Forbidden Paradise(1924), che in Italia uscì col titolo La Czarina, era uno di quei film di cui si parlava per allusioni o interposta persona: si conosceva la trama — le avventure erotiche della regina di un immaginario stato europeo — ma ci si doveva accontentare di vedere solo quello che era rimasto, più o meno due terzi dell’originale. Fino a quando il Museum of Modern Art con il sostegno della fondazione di George Lucas e della Film Foundation ha recuperato due copie (incomplete) che, messe a confronto con alcuni negativi (lacunosi anche loro), hanno permesso di ritrovare la quasi integralità del film, che sarà presentato in prima mondiale venerdì 12 Pordenone alla presenza della figlia del regista, Nicola Lubitsch.

Mescolando abilmente passato e presente (l’ambientazione sembra quella tipica del Settecento più favolistico ma all’improvviso entra in campo un’automobile), kitsch e satira politica (i rivoluzionari non sai se sono più comici o minacciosi), il film ribalta lo schema del maschio conquistatore attribuendone tutte le caratteristiche a una donna che non si preoccupa nemmeno delle apparenze e per conquistare l’ufficiale su cui ha messo gli occhi «esilia» la fidanzata senza un attimo di compassione. Salvo naturalmente redimersi nel finale (anche perché ha messo gli occhi su un’altra preda).

È proprio vero: Lubitsch non delude mai, in questo caso anche per merito di una serie di scoppiettanti gag che ora si possono finalmente gustare nella loro forma originale, dal taglio di capelli «alla maschietta» della sovrana che fa piangere le tradizionalissime dame di corte al mal di schiena del ciambellano (Adolphe Menjou) costretto a spiare sempre dal buco della serratura e preoccupato per le finanze dello stato (mette mano al portafoglio per tacitare chi vuol fare la rivoluzione: «Alla prossima — si legge in una didascalia — il regno va in bancarotta») fino alle innumerevoli porte che si aprono e si chiudono per far entrare e uscire gli amanti della regina (lei è l’affascinante Pola Negri, già al centro dei gossip hollywoodiani per la sua tumultuosa e fulminea storia con «Sciarli» Chaplin — così lo chiamava — e poi con Rodolfo Valentino). Non manca nemmeno un pesciolino che «censura» il bacio riflesso nell’acqua del giovane capitano e della sua fidanzata (e che farà ricordare ai cinefili italiani il «pesce democristiano» che, trent’anni dopo, impedirà a Totò di ammirare le grazie nude di Isa Barzizza in Fifa e arena: una citazione?).

E a proposito di «anticipazioni», quest’anno Pordenone ha messo in programma anche una serie di mini-spot pubblicitari, rigorosamente muti, che venivano proiettati al cinema negli intervalli. La corsa al consumismo esisteva anche all’inizio del Novecento; non deve stupire che sfruttasse il neonato cinema per invitare all’acquisto: curioso invece che per lo stesso prodotto, un sapone per sgrassare, si sottolineasse l’uso «di genere», quello per gli uomini (alla fine del lavoro in fabbrica) e quello per le donne (per i lavori domestici), dividendo lo schermo in due. Dimostrando che già cent’anni fa la pubblicità anticipava il cinema nello sperimentare linguaggi nuovi se non avanguardistici.

ENAMORADA by Emilio Fernández to open The Classics, Festival of the Films That Will Live Forever 2018

With the support of the The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, UCLA Film & Television Archive, Televisa, and the Material World Charitable Foundation:

ENAMORADA by Emilio Fernández

to open The Classics, Festival of the Films That Will Live Forever 2018

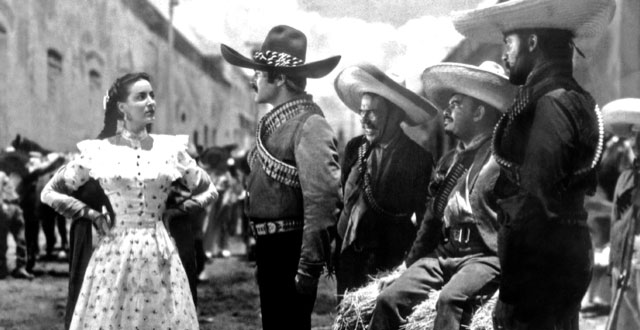

ENAMORADA by Emilio Fernández had its restoration premiere this year at the Cannes Film Festival and also, had an unforgettable screening at Il Cinema Ritrovato. Now, this extraordinary Mexican film will have its South American premiere in Bogotá, Colombia at the Classics.

Founder and Chair of The Film Foundation, Martin Scorsese stated: " I’m very happy to know that ENAMORADA will open The Classics, and pleased that The Film Foundation is continuing its support for this festival. ENAMORADA, directed by Emilio Fernández, was a huge hit in Mexico and catapulted Pedro Armandáriz and Maria Félix to stardom. The film takes place during the Mexican Revolution and was inspired by Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew. This extraordinary restoration, by the UCLA Film & Television Archive and TFF’s World Cinema Project, in association with Filmoteca de la UNAM and Fundacion Televisa, and funded by the Material World Charitable Foundation, highlights the great work of the director, actors, and the film’s legendary cinematographer, Gabriel Figueroa. The soundtrack, restored by Audio Mechanics, includes the beautiful performance of “Malagueña Salerosa,” one of many highlights of this beloved film. I’m grateful to Olivia Harrison and the Material World Charitable Foundation, for their passionate commitment to preserving and presenting this and many other masterpieces of cinema.”

Olivia Harrison, of the Material World Charitable Foundation added: "While my late husband, George Harrison, was growing up in Liverpool, he would watch American horror films and Westerns. At the same time, Martin Scorsese was living in New York City watching Italian Neorealist films, and I was in Los Angeles, watching Mexican films that were constantly playing in my home. Film has an amazing power to transcend time and space to connect and unite all of us. Regardless of where or when you grew up, there are some works of cinema that are timeless and speak to audiences of all backgrounds and generations; ENAMORADA is one of them. It is a film that is very dear to me and I am thrilled that it is screening in Bogotá as the part The Classics."

In its first version, the classics had incredible success, and this year the festival will be national and across three cities in Colombia. "This is a beautiful opportunity to bring all these unforgettable classics to the big screen, which is the place where they belong. I am thrilled with the extraordinary support of The Film Foundation; this festival was created because of them.” Said Co-Founder of the Classics, Juan Carvajal.”

The Classics will take place November 8th - 14th.

The Classics, Festival of the Films That Will Live Forever is supported by The Film Foundation, Cine Colombia, Caracol Cine, British Council Colombia, Park Circus, Mei Lab Digital, Videoactividad & Gas Natural

56th NYFF Retrospective & Revivals Sections Include Films from Fassbinder, Oshima, Mambéty & More

Leonard Pearce

Following their impressively varied Main Slate section and Projections lineup, the full slate for Retrospective and Revivals at the 56th New York Film Festival have been announced. After last year’s Robert Mitchum retrospective, this year’s edition is split into three parts, paying tributing to the late Dan Talbot and Pierre Rissient, as well as spotlighting a trio of documentaries that delve into cinema history.

“For Pierre and Dan, two genuine heroes, everything to do with cinema was urgent. This year’s retrospective section pays tribute to both men, who passed away within six months of each other,” NYFF Director and Selection Committee Chair Kent Jones said.

Talbot, founder of New Yorker Films and longtime director of Lincoln Plaza Cinemas, will be honored with personal favorites from Bernardo Bertolucci, Straub-Huillet, Nagisa Oshima, Jean-Luc Godard, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and more. Meanwhile, producer, publicist, distributor, curator, and cinema polymath Pierre Rissient’s section will feature works from Clint Eastwood, Joseph Losey, King Hu, Raoul Walsh, Fritz Lang, and more.

Amongst the Revivals sections, a number of major new restorations will be presented, including Edgar G. Ulmer’s noir classic Detour, Djibril Diop Mambéty’s neocolonialist satire Hyenas, Alexei Guerman’s Khrustalyov, My Car!, Delmer Daves’ The Red House, and more.

Check out the lineup of both sections exclusively below.

FILMS & DESCRIPTIONS

REVIVALS

Detour

Dir. Edgar G. Ulmer, USA, 1945, 68m

Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1945 classic, made at the Poverty Row production company PRC somewhere between 14 and 18 shooting days for $100,000, has come to be regarded, justifiably, as the essence of film noir. Ulmer and his team turned the very cheapness of the enterprise into an aesthetic asset and created a film experience that reeks of sweat, rust, and mildew. For years, Detour was only available in dupey, substandard prints, which seemed appropriate. In the ’90s, a photochemical restoration improved matters, but the quality was far from optimal. Now we have a restoration of a different order, made from vastly superior elements. “To be able to see so much detail in the frame, in the settings and in the faces of the actors,” says Martin Scorsese, “is truly startling, and it makes for a far richer and deeper experience.”

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation, in collaboration with the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique, The Museum of Modern Art, and the Cinémathèque Française, with funding from the George Lucas Family Foundation.

Enamorada

Dir. Emilo Fernández, Mexico, 1946, 99m

This wildly passionate and visually beautiful love story from director Emilio Fernandéz and cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, a follow-up to their wildly successful Maria Candelaria, remains one of the most popular Mexican films ever made. As Farran Smith Nehme has written, it was “one of the biggest hits of Fernández’s career and a high-water mark for nearly everyone involved.” The romance between between a revolutionary General (Pedro Armendariz) and the daughter of a nobleman (Maria Félix) set during the Mexican revolution (in which Fernandéz himself fought) was inspired by The Taming of the Shrew and, for the finale, by the end of Sternberg’s Morocco.

Restoration led by UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project in collaboration with Fundacion Televisa AC and the UNAM Filmoteca, funded by Material World Charitable Foundation.

Hyenas / Ramatou

Dir. Djibril Diop Mambéty, Senegal/Switzerland/France, 1992, 110m

“When a story ends—or ‘falls into the ocean,’ as we say—it creates dreams,” said the great Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty in an interview after the completion of his second film, Hyenas, a wildly freeform adaptation of Friedrich Dürrenmatt’s The Visit. A wealthy woman (Ami Diakhate) returns to her—and Mambéty’s—home village, and offers the inhabitants a vast sum in exchange for the murder of the local man who seduced and abandoned her when she was young. “I do not refuse the word didactic,” said Mambéty of his very special body of work, and of the particular plight of African cinema. “My task was to identify the enemy of humankind: money, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. I think my target is clear.” A Thelma Film AG release.

Restored over the course of 2017 by Eclair Digital in Vanves, France. Restoration was taken on by Thelma Film AG (Switzerland).

I Am Cuba

Dir. Mikhail Kalatozov, Cuba/USSR, 1964, 108m

Mikhail Kalatozov’s wildly mobile, hallucinatory film was initially rejected by both Cuban and Soviet officials for excessive naiveté and an insufficiently revolutionary spirit, and went largely disregarded and almost unknown for nearly 30 years. That all changed in the early nineties—a remarkable era in film culture, chock full of rediscoveries—when G. Cabrera Infante programmed it at the Telluride Film Festival, and Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola co-presented a Milestone Films release. I Am Cuba is a one-of-a-kind film experience, a visually mind-bending bolt from the historical blue.

Milestone Film & Video’s 4K restoration from the original Gosfilmofond 35mm interpositive and mag tracks was done at Metropolis Post with Jason Crump (colorist) and Ian Bostick (restoration artist). 4K scan by Colorlab, Rockville, MD.

Khrustalyov, My Car! / Khrustalyov, mashinu!

Dir. Alexei Guerman, USSR/France, 1998, 150m

The time is 1953, the place is Moscow; the Jewish purges are still on, and Stalin is on his deathbed. When General Yuri Glinsky, a military surgeon, tries to escape, he is abducted, taken to the lowest rungs of hell, and deposited at the heart of the enigma. Alexei Guerman’s deeply personal penultimate film is a work of solid and constant disorientation, masterfully orchestrated. Enigmatic phrases, sounds, gestures, and micro-events pass before our eyes and ears before we or the alternately jumpy and exhausted characters can make sense of them. Guerman’s lustrous black and white images and meticulously constructed soundscape are permeated with the feel of life in a totalitarian society, where something monumental is underway but no one knows precisely what or when or how it will break.

The original 35mm fine grain positive was scanned in 2K resolution on an Arriscan at Eclair, Paris. The film was graded and restored at Dragon DI, Wales. Restoration supervised by James White, Arrow Films; restoration produced by Daniel Bird.

Neapolitan Carousel

Dir. Ettore Giannini, Italy, 1954, 129m

One of the first color films made in Italy, Ettore Giannini’s 1954 film version of his stage musical begins in the present day, with sheet music hanging on a barrel organ blown through the streets of Naples: every individual song tells a story of the history of the city, from the Moorish invasion in the 14th century through the arrival of the Americans at the end of WWII. Giannini assembled an amazing roster of talent for his film, including one-time Ballets Russes principal dancer and Powell-Pressburger mainstay Léonide Massine (who also choreographed), the great comic actor Paolo Stoppa, and a young Sophia Loren.

Restored by the Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and The Film Foundation with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

None Shall Escape

Dir. André de Toth, USA, 1944, 85m

The Hungarian emigré André de Toth directed this unflinching look at the rise of Nazism right before the end of the war, the first Hollywood film to address Nazi genocide. Written by Lester Cole, soon to become a member of the Hollywood Ten, None Shall Escape is structured as a series of flashbacks that dramatize the testimony of witnesses in a near-future postwar tribunal. Alexander Knox is the German everyman, a WWI vet who slowly, gradually accepts National Socialism and becomes a mass murderer. With Marsha Hunt—her career and Knox’s would both be affected by the Red Scare. A Sony Pictures Repertory release.

4K digital restoration from original nitrate negative and original nitrate track negative.

The Red House

Dir. Delmer Daves, USA, 1947, 100m

This moody, visually potent film, directed by Delmer Daves and independently produced by star Edward G. Robinson with Sol Lesser, is something of an anomaly in late ’40s moviemaking, a piece of contemporary gothic Americana. Robinson plays Pete, a farmer who shares his home with his sister (Judith Anderson) and his adopted niece Meg (Allene Roberts). Meg becomes increasingly attached to a sweet local boy (Lon McAllister), and together they venture into the woods in search of a red house that Pete has forbidden them to enter. The emotional heart of The Red House can be found in the extraordinary close-ups of Roberts and McAllister, shot by the great DP (and frequent John Ford collaborator) Bert Glennon.

Restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the George Lucas Family Foundation.

Spring Night, Summer Night

Dir. J.L. Anderson, USA, 1967, 82m

J.L. Anderson’s haunted Appalachian romance occupies a proud place alongside such similarly hand-crafted, off-the-grid American independent films as Carnival of Souls, The Exiles, Night of the Living Dead, and Wanda. Made in coal-mining country in northeastern Ohio with local amateur actors, the film is carefully observed (Anderson and his producer Franklin Miller spent two years scouting locations becoming familiar with the place and the people) and beautifully and lovingly realized. Spring Night, Summer Night has had an extremely checkered history, including a release in a version crudely recut for the exploitation market with the title Miss Jessica Is Pregnant. It was invited to the 1968 New York Film Festival, only to be unceremoniously bumped to make way for John Cassavetes’s Faces. Fifty years later, we’re re-extending the invitation and promising that it’s solid.

A Restoration and Reconstruction Project of Cinema Preservation Alliance by Peter Conheim and Ross Lipman. Produced by Nicolas Winding Refn.

Tunes of Glory

Dir. Ronald Neame, UK, 1960, 106m

Ronald Neame’s adaptation of James Kennaway’s novel is a spare, dramatically potent war of nerves, about the power struggle between a tough lower-middle-class Scottish Major due to be replaced as Battalion commander of a Highland regiment and an aristocratic Colonel traumatized by captivity during the war. At its center are two breathtaking performances: John Mills as the Colonel and Alec Guinness, in a genuine tour de force, as the Major (apparently, after they had read the script, each actor had originally wanted to play the other’s role). With Dennis Price, Kay Walsh, Susannah York, and Gordon Jackson.

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation in collaboration with Janus Films and The Museum of Modern Art. Restoration funding provided by the George Lucas Family Foundation.

The War at Home

Dir. Glenn Silber and Barry Alexander Brown, USA, 1979, 100m

This meticulously constructed 1979 film recounts the development of the movement against the American war in Vietnam on the Madison campus of the University of Wisconsin, from 1963 to 1970. Using carefully assembled archival and news footage and thoughtful interviews with many of the participants, it culminates in the 1967 Dow Chemical sit-in and the bombing of the Army Math Research Center three years later. One of the great works of American documentary moviemaking, The War at Home has also become a time capsule of the moment of its own making, a welcome emanation from the era of analog editing, and a reminder of how much power people have when they take to the streets in protest. A Catalyst Media Productions release.

New 4K restoration by IndieCollect.

RETROSPECTIVE

Tribute to Dan Talbot

Before the Revolution

Dir. Bernardo Bertolucci, Italy, 1964, 105m

Dan Talbot began as an exhibitor, and he started his distribution company, New Yorker Films, for the best possible reason: he saw a film that he loved and he wanted to share it with as many people as possible. The film was Bernardo Bertolucci’s masterful second feature, a deeply personal portrait of a generation gripped by political uncertainty. Set in the director’s hometown of Parma, it follows the travails of a young student struggling to reconcile his militant views with his bourgeois lifestyle (and his fiancée), who drifts into a passionate affair with his radical aunt. One of the key films of the ’60s, Before the Revolution set many aspiring filmmakers on their own autobiographical courses. 35mm print from Istituto Luce Cinecittà.

Straub-Huillet Program:

Machorka-Muff

Dir. Jean-Marie Straub, Danièle Huillet; West Germany; 1963; 18m

The Bridegroom, the Comedienne and the Pimp

Dir. Jean-Marie Straub, Danièle Huillet; West Germany; 1968; 23m

Not Reconciled

Dir. Jean-Marie Straub, Danièle Huillet; West Germany; 1965; 55m

In 1966, Dan and Toby Talbot went to a party thrown by Bertolucci and his friend and co-writer Gianni Amico in Rome. Suddenly, the bell rang. “Shh-sh,” said Bertolucci. “Get rid of the pot! Put the drinks away. The Straubs are here!” That someone would pick up any single film directed by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet is utterly unthinkable in the context of the present moment, but for decades New Yorker Films handled all of them. These three films, often shown together, are among their very best: an idiosyncratic adaptation of Heinrich Böll’s short story “Bonn Diary,” about a former Nazi colonel cynically reflecting on the sheer stupidity of the bourgeoisie; a three-part short comprised of a nocturnal tour of Munich, a high-speed stage production of Bruckner’s Sickness of Youth, and the marriage of James and Lilith, who guns down her pimp (played by Rainer Werner Fassbinder); and their stunning, thrillingly compressed adaptation of Böll’s novel Billiards at Half-Past. A Grasshopper Film release.

The Ceremony

Dir. Nagisa Oshima, Japan, 1971, 123m

New Yorker developed a close relationship with the filmmaker once known as “the Japanese Godard,” Nagisa Oshima, and they programmed a groundbreaking retrospective of his early films during their brief tenure at the Metro on 100th Street. This disarmingly atmospheric portrait of a family’s collective psychopathology recounts the saga of the Sakurada clan, whose decline plays out over the course of 25 years and multiple funerals and weddings. Operating at the height of his iconoclastic powers, Oshima renders the family’s unraveling with an arresting sense of foreboding and an air of gothic fatalism, enriched by Tôru Takemitsu’s quintessentially modernist score.

Every Man for Himself / Sauve qui peut (la vie)

Dir. Jean-Luc Godard, France/Austria/West Germany/Switzerland, 1980, 87m

“Dan jumped straight to the point,” wrote Toby in her book The New Yorker Theater and Other Scenes from a Life at the Movies. “‘I love your work and would like to distribute anything you make.’” Over the years, New Yorker handled many of Godard’s films, including his return to 35mm character-based storytelling after a decade of experimentation in video. What Godard called his “second first film” is a moving portrait of restless, intertwining lives, and the myriad forms of self-debasement and survival in a capitalist state, with Jacques Dutronc (as “Paul Godard”), Nathalie Baye, Isabelle Huppert, and, in an unforgettable anti-cameo, the voice of Marguerite Duras. An NYFF18 selection.

The American Friend

Dir. Wim Wenders, West Germany/France, 1977, 125m

Dan Talbot and New Yorker Films put the New German Cinema of the 1970s on the map in this country, and one of their key titles was Wim Wenders’s spellbinding adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley’s Game (and a little bit of Ripley Underground). Dennis Hopper is the sociopathic charmer Tom Ripley, transformed by Wenders into an urban cowboy peddler of forged paintings who ensnares Bruno Ganz’s gravely ill Swiss-born art framer into a plot to assassinate a Mafioso. Shot in multiple New York and European locations in low-lit, cool blue and gold tones by the great Robby Müller, this brooding, dreamlike thriller conjures a world ruled by chaos and indiscriminate American dominance. It also features a stunning array of performances and guest appearances by filmmakers, including Nick Ray, Gérard Blain, Sam Fuller, Jean Eustache, Daniel Schmid, and Peter Lilienthal. An NYFF15 selection.

The Marriage of Maria Braun

Dir. Rainer Werner Fassbinder, West Germany, 1979, 120m

“I bought 11 Fassbinders in one shot, like rugs,” Dan told Anthony Kaufman in a 2009 interview. As was the case with every New Yorker acquisition, the motive was not financial. So one can imagine the surprise at their offices when this 1979 film about a poor German soldier’s wife (Hanna Schygulla) who uses her wiles and savvy to rise as a businesswoman and take part in the “wirtschaftwunder” or postwar economic miracle, became an arthouse hit—per François Truffaut, this was the movie that broke Fassbinder “out of the ivory tower of the cinephiles” and earned him the acclaim he had always sought. The Marriage of Maria Braun was also the Closing Night selection of the 17th New York Film Festival.

My Dinner with André

Dir. Louis Malle, USA, 1981, 110m

When Dan read Wallace Shawn and André Gregory’s script for My Dinner with André, he was so excited that he helped Louis Malle procure production funding from Gaumont. The film, an encounter between the two writers playing themselves discussing mortality, money, despair, and love over a meal at an upper west side restaurant (according to Gregory, Malle’s one direction was “Talk faster”), becoming a sensation at the art house, playing to packed houses for a solid year, and a favorite on the brand-new home video circuit. My Dinner with André is entertaining, confessional, funny, moving, and suffused with melancholy and joy…like life.

Tribute to Pierre Rissient

Manila in the Claws of Light / Maynila: Sa mga kuko ng liwanag

Dir. Lino Brocka, Philippines, 1975, 124m

Pierre Rissient championed the work of countless filmmakers—as a programmer of the MacMahon Theatre in Paris, as a publicist in partnership with his lifelong friend Bertrand Tavernier, as a scout for Cannes, as a distributor and producer, and always as a lover of cinema with an avid desire to always learn and see more. As Todd McCarthy wrote, it was Pierre who “single-handedly brought the work of the late Filipino director Lino Brocka to the world’s attention.” This searing melodrama, with Bembel Roco and Hilda Koronel as doomed lovers, is one of Brocka’s greatest. “Lino knew all the arteries of this swarming city,” wrote Pierre, “and he penetrated them just as he penetrated the veins of the outcasts in his films. Sometimes a vein would crack open and bleed. And that blood oozed onto the screen.”

A Touch of Zen

Dir. King Hu, Hong Kong, 1971/1975, 200m

Pierre developed a special love for Asia and its many cinemas, and he was the one who properly introduced the great wuxia master King Hu to the west, bringing the uncut version of his masterpiece, A Touch of Zen, to the 1975 Cannes Film Festival. Supreme fantasist, Ming dynasty scholar, and incomparable artist, Hu elevated the martial-arts genre to unparalleled heights. Three years in the making and his greatest film, A Touch of Zen was released in truncated form in Hong Kong in 1971 and yanked from theaters after a week. Four years later, after Rissient saved the film from oblivion and it won a grand prize for technical achievement, the unthinkable occurred: King Hu received an apology from his studio heads.

Time Without Pity

Dir. Joseph Losey, UK, 1957, 85m

Pierre was close to many of the American writers and directors who had been through the blacklist, including Jules Dassin, Abraham Polonsky, John Berry, and Cy Endfield, and he was a great admirer of the films of Joseph Losey (his feelings about the man himself were another matter). Rissient was crucial in bringing attention to this consummately tense noir, one of Losey’s greatest films. The narrative, unfurling at a breakneck pace, chronicles the plight of a recovering alcoholic (Michael Redgrave) with a mere 24 hours to prove the innocence of his son, accused of murdering his girlfriend. The first film that Losey signed with his own name after his flight to Europe in the early ’50s, Time Without Pity established him as an essential auteur in the eyes of French cinephiles.

Play Misty for Me

Dir. Clint Eastwood, USA, 1971, 102m

When Clint Eastwood won his first Oscar, in 1992 for Unforgiven, he thanked “the French” for their support. But it was one French citizen in particular who was there from the start of his career as a filmmaker. Eastwood’s first film, about a casual romantic encounter between a Northern California DJ (played by the director) and a woman named Evelyn (Jessica Walter) that turns harrowingly obsessive, is an essential film from an essential moment in cinema known as Hollywood in the ’70s. While the film was well-received, it was Pierre who recognized that Play Misty for Me marked the debut of a truly distinctive talent. From there, a close and abiding friendship bloomed.

Mother India

Dir. Mehboob Khan, India, 1957, 172m

When we gave this film a run at the Walter Reade Theater in 2002, Pierre was only too happy to provide a simple but eloquent quote: “Air…space…light—that’s Mother India.” This seminal Bollywood film, a remake of Khan’s earlier Aurat (1940), is about the trials and tribulations of Radha (Nargis), a poor villager caught in the historic whirlwind of the struggles endured in her country after gaining its independence from Britain. Striving to raise her sons and make ends meet in the face of poverty and natural disasters alike, Radha endures through the strength of her convictions and her unflappable sense of morality. Mother India is a powerful experience, for both its place in film history and its incarnation of human resilience.

House by the River

Dir. Fritz Lang, USA, 1950, 89m

There were few filmmakers whose work Pierre revered more than Fritz Lang, whom he counted among his friends. When Lang came to the Cinémathèque Française for a retrospective of his work in the late 1950s, Pierre and Claude Chabrol asked him about this wild gothic period melodrama, made at Republic Pictures, starring Louis Hayward and Jane Wyatt, a print of which could not be found and which was still unseen in France. Lang, said Pierre, “could describe shot by shot the first ten, twelve minutes of the film. It was almost as if we were seeing the film.” Pierre not only found a way of seeing House by the River, he acquired the rights and distributed the film himself.

The Man I Love

Dir. Raoul Walsh, USA, 1947, 96m

Raoul Walsh was another honored figure in Pierre’s pantheon. On one occasion, when the subject of one of Walsh’s films came up, Pierre simply whistled in admiration. This 1947 film, somewhere between noir, musical, and melodrama, is one of Walsh’s least recognized and most moving, rich in the “daily human pathetique” that Manny Farber identified as the director’s richest vein. Ida Lupino is the Manhattan lounge singer who heads to Los Angeles to live with her family and start a new life. Bruce Bennett is the musician she falls for, and Robert Alda is the brash club owner who won’t take no for an answer. If one were pressed for a single word to describe this movie, it would be “soulful.”

Three Documentaries on Cinema

In this year’s retrospective section, we also include three special and very different documentaries about the movies: a lament for Viennese film critic and festival director Hans Hurch, a portrait of the great cinema pioneer Alice Guy-Blaché, and a tribute to Ingmar Bergman.

Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché

Dir. Pamela B. Green, USA, 2018, 103m

Alice Guy-Blaché was a true pioneer who got into the movie business at the very beginning—in 1894, at the age of 21. Two years later, she was made head of production at Gaumont and started directing films. She and her husband moved to the United States, and she founded her own company, Solax, in 1910—they started in Flushing and moved to a bigger facility in Fort Lee, New Jersey. But by 1919, Guy-Blaché’s career came to an abrupt end, and she and the 1000 films that bore her name were largely forgotten. Pamela B. Green’s energetic film is both a tribute and a detective story, tracing the circumstances by which this extraordinary artist faded from memory and the path toward her reclamation. Narration by Jodie Foster.

Preceded by:

Falling Leaves (1912)

One of Alice Guy-Blaché’s most beautiful films, this two-reeler concerns a girl who tries to keep her consumptive sister alive by magical means.

Music composed and performed by Makia Matsumura. A collaborative restoration for the Alice Guy-Blaché retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Mastered from a 2K scan of a surviving nitrate print received by the Library of Congress in 1983 from the Public Archives of Canada/Jerome House Collection. 2018 Digital restoration produced by Bret Wood for Kino Lorber, Inc.

Introduzione all’Oscuro

Dir. Gastón Solnicki, Argentina/Austria, 2018, 71m

North American Premiere

The new film from Gastón Solnicki (Kékszakállú, NYFF54) is a tribute to his great friend Hans Hurch, one-time film critic and assistant to Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, and director of the Vienna International Film Festival from 1997 to his unexpected death from a heart attack last July at the age of 64. Solnicki pays tribute to Hurch by creating a cinematic form for his own mourning. He doesn’t simply visit his friend’s old haunts, he responds rhythmically, in images and sounds, to Hurch’s recorded voice delivering admonitions and gentle warnings during the editing of an earlier film. Introduzione all’Oscuro is truly a work of the cinema, and a moving communion with a friend whose presence is felt in the memory of the places, the people, the coffee, and the films he loved.

Searching for Ingmar Bergman

Dir. Margarethe von Trotta, Germany/France, 2018, 99m

U.S. Premiere

On the occasion of Ingmar Bergman’s centenary comes this lovely, personal film from one of his greatest admirers, Margarethe von Trotta. This is a tribute from an artist with a such a deep affinity for the subject that it opens to genuine and sometimes disquieting inquiry. In his writings and in his films, Bergman himself strove for an honest accounting and true self-revelation, but it is fascinating to hear and see the observations of loved ones and collaborators (often one and the same), particularly his son Daniel, whose relationship with his father was multi-layered. A rich and quietly absorbing portrait of an immense artist. An Oscilloscope Laboratories release.

Passes for the 56th NYFF, taking place from September 28-October 14 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, are now on sale. Single tickets go on sale on September 9.

We have lost about 70 per cent of our films

Jaybrota Das

Award-winning Indian filmmaker, producer, film archivist and restorer Shivendra Singh Dungarpur will organise his next Film Preservation and Restoration Workshop India (FPRWI-2018) in Calcutta from November 15 to 22.

“The reason we are doing it in Calcutta this year is that while Bengal is the home of legendary filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak, Ajoy Kar, Tapan Sinha, Tarum Majumdar and so many more, sadly very little has been preserved of this great heritage. This is particularly ironic as Bengal is celebrating 100 years of Bengali cinema this year. We hope that the workshop will wake people up to the urgent need to save their films as our goal is to make a real difference,” said Dungarpur.

FPRWI-2018 is an intensive week-long workshop that covers both lectures and practical classes in the best practices of the preservation and restoration of both filmic and non-filmic material that is taught by a faculty of international experts from leading institutions around the world. The workshop usually has about 50 participants and about 25 international faculty and is certified by FIAF. Applications are open to India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia.

In the run-up to the workshop The Telegraph had a chat with Dungarpur, who had hosted distinguished filmmaker Christopher Nolan during his visit to India last year on a similar platform to preserve rare cinematic gems.

TT: How widely does such restoration workshops help? Does it only help the film fraternity and films in general or does it allow participation from film enthusiasts?

Dungarpur: When Film Heritage Foundation conducted our first film preservation and restoration workshop in Mumbai in 2015, people were not aware that films needed to be preserved. And we’re not talking just about the common man, but also the film industry. When we started the foundation in 2014, we realised that saving our film heritage had to be taken up on a war-footing. Not only had we lost about 70 per cent of our film heritage by the 1950s, we continue to lose films, even contemporary films, every day. We have seen a remarkable change in just a few years. The film industry has begun to comprehend the importance of preserving their films - both photochemical and digital ones. For instance, our foundation preserves the films of Amitabh Bachchan, Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Mani Ratnam, Farhan Akhtar, N.N. Sippy, Vishal Bhardwaj and many others and by this I mean storing their 35mm prints in temperature-controlled conditions and maintaining them. In just three years we have introduced 150 individuals to film preservation and restoration. We are building a movement to save our film heritage.

• How much change has you been able to bring in the mindset of producers who have not been able to maintain their assets?

• If we have not preserved our films, we will have nothing to restore. The loss of India’s film heritage has been colossal. Around 1,700 silent films were made in India of which the National Film Archive of India (NFAI) have only five to six complete films and 15 to 20 films in fragments. The film industry in Madras made 124 films and 38 documentaries in the silent era. Only one film survives, Marthanda Verma (1931). By 1950, India had lost 70 to 80 per cent of our films. And we don’t have to go so far back. Gulzar Saheb could not find the original negative of Maachis, a 1995 film. Mani Ratnam has lost many of his original negatives, which people do not realise, still need to be preserved even if you have a digital copy. The only world-class restoration of Indian films have been the restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy that was done by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and the Criterion Collection, Uday Shankar’s Kalpana and Ritwik Ghatak’s Titas by Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

• What are the procedures involved in restoring a film?

• The approach is the same as restoring a work of art or a manuscript. You don’t work on a photocopy, you restore the original. For instance in the case of the Apu Trilogy, the original negatives were burnt in a studio fire, and months were spent on the repair of these negatives before getting into the process of digital restoration. The task of restoration involves studying the film and its production history, understanding the filmmaker’s vision or his limitations, knowing the work of the cinematographer, the art director, the costume designer, etc.