The World Cinema Project (WCP) preserves and restores neglected films from around the world. To date, 67 films from Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, Central America, South America, and the Middle East have been restored, preserved and exhibited for a global audience. The WCP also supports educational programs, including Restoration Film Schools; intensive, results-oriented workshops allowing students and professionals worldwide to learn the art and science of film restoration and preservation. All WCP titles are available for exhibition rental by clicking "Book This Film."

GHATASHRADDHA

Director: Girish Kasaravalli

WRITTEN BY: Girish Kasaravalli, K.V. Subanna

EDITING: Umesh Kulkarni

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: S. Ramachandra

STARRING: Narayan Bhatt, Ramaswamy Iyengar, Janganath, Ajith Kumar, Shanta Kumari, Meena Kuttappa, Ramakrishna, Suresh

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: India

LANGUAGE: Kannada

COLOR INFO: B&W

RUNNING TIME: 115 minutes

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Film Heritage Foundation at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Girish Kasaravalli. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Restored using the 35mm original camera negative preserved at the NFDC-National Film Archive of India and a 35mm print preserved at the Library of Congress.

HOUSEMAID, THE

HANYO

Director: Kim Ki-Young

WRITTEN BY: Kim Ki-Young

EDITING: Kim Ki-Young

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Kim Deok-jin

PRODUCER: Kim Young-chul

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Han Sang-Ki

ART DIRECTOR: Park Seok-in

STARRING: Lee Eunshim (Housemaid), Kim Jin-kyu (Dong-sik), Ju Jeung-nyeo (Dong-sik’s wife), Um Aeng-ran (Cho Kyung-hee)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: South Korea

LANGUAGE: Korean with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 110 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Korean Munye Films Co., Ltd.

PRODUCER: Kim Young-chul

Restored in 2008 by the Korean Film Archive (KOFA), in association with The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project and HFR-Digital Film laboratory. Additional restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

Kim Ki-young’s Hanyo, or The Housemaid, is one of the true classics of South Korean cinema, and when I finally had the opportunity to see the picture, I was startled. That this intensely, even passionately claustrophobic film is known only to the most devoted film lovers in the west is one of the great accidents of film history. I’m proud that the World Cinema Foundation is participating in the restoration and preservation of this remarkable picture. I am eager for more people to get to know and love The Housemaid.

–Martin Scorsese, February 2008

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Hanyo has been restored digitally by the Korean Film Archive (KOFA) with the support of the World Cinema Foundation. The original negative of the film was found in 1982 with two missing reels, 5 and 8. In 1990 an original release print with hand-written English subtitles was found and used to complete the copy. This surviving print was highly damaged, and the English subtitles occupied almost half of the frame area. The long and complex restoration process has involved the use of a special subtitle-removal software and included flicker and grain reduction, scratch and dust removal, color grading.

Image: © Courtesy of Korean Film Archive

IFE / 3ÈME FESTIVAL DES ARTS

Director: Paulin Soumanou Vieyra

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Senegal

LANGUAGE: French with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 13 minutes

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in collaboration with the Ministère de la Culture et du Patrimoine Historique de Sénégal – Direction du Cinéma. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO―in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna―to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The 4K restoration was completed using a 16mm print preserved by the Direction du Cinéma in Senegal. With special thanks to Tiziana Manfredi and Marco Lena.

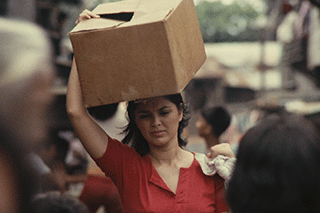

INSIANG

Director: Lino Brocka

WRITTEN BY: Mario O’Hara and Lamberto Antonio

EDITING: Augusto Salvado

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Conrado Baltazar

PRODUCER: Miguel De Leon Severino

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Max Jocson

SOUND: Luis Reyes, Ramon Reyes

STARRING: Hilda Koronel, Mona Lisa, Ruel Vernal, Rez Cortez, Marlon Ramirez

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Philippines

LANGUAGE: Tagalog with French and English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 124 minutes

PRODUCER: Miguel De Leon Severino

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/ L’Immagine Ritrovata. Restoration funded by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the Film Development Council of the Philippines.

I’m so pleased that Insiang, the second of the great Lino Brocka’s films that we’ve managed to restore, has been selected for this year’s Cannes Classics: back in 1976, this extraordinary family melodrama was the first picture from the Philippines ever selected for Cannes. Brocka was like a force of nature in world cinema, and Insiang was among his greatest achievements. - Martin Scorsese, May 2015

Insiang is, first and foremost a character analysis: a young woman raised in a miserable neighborhood. I need this character to recreate the ‘violence’ stemming from urban overpopulation, to show the annihilation of a human being, the loss of human dignity caused by the physical and social environment and to stress the need for changes to these life conditions […] My characters always react through fighting. I have conceived Insiang like an immoral story: two women share the same man, the daughter avenges herself and, in the end, she reveals herself: she had conspired to kill her mother’s lover without having ever loved him, so that the murder was, in fact, unnecessary. Censorship refused this ending.” - Lino Brocka

In 1977 I was in Sydney for the film festival. Before going home, I zigzagged my way back through Jakarta, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Hong-Kong, Manila and Seoul, to discover a new filmmaker and an unknown film: Insiang by Lino Brocka. When Insiang was released on December 17, 1976, it did not do well, and led to the collapse of CineManila, the company founded by Brocka in 1974 after the extraordinary success of Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang. The shooting of Insiang began on December 1 and lasted 11 days. Knowing these dates is important as they reveal the extreme urgency he felt, and his unique, authentic desire to make this film. Insiang also presents an unusual, brilliant mise-en-scène which shows the characters being torn apart by passion, by a sort of ardent energy. I am very pleased that, two years after Manila in the Claws of Light, Cannes Classics is showcasing another restoration of a Brocka film. I still remember the excitement, along rue Antibes, surrounding the screening of Insiang at the Quinzaine de Réalisateurs, in 1978. That was a very fulfilling and emotional experience, and I’m sure the same will be true today. - Pierre Rissient

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Insiang was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negatives deposited at LTC laboratories by producer Ruby Tiong Tan.

The negative was wet-scanned at 4K resolution and digital restoration was very time-consuming. Some portions of the film, where the negative was intercut to the internegative were extremely damaged and two shots were replaced by use of a 35mm positive print preserved at the BFI National Archive.

Despite an overall acceptable state of preservation, the original optical sound negative presented critical recording issues. The sound restoration required considerable effort to try and solve or minimize the severe metallic hiss and distortions. Several acquisition methods were tested, leaving, however, very little room for improvement.

KALPANA

Director: Uday Shankar

WRITTEN BY: Uday Shankar, Amritlal Nagar

EDITING: N.K. Gopal

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: K. Ramnoth

FROM: National Film Archive of India

STARRING: Uday Shankar (Udayan & Writer), Amala Uday Shankar (Uma), Lakhmt Kanta (Kamini), Dr. G.V. Subbarao (Drawing Master), Brijo Behari Banerji (Uma’s Father)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: India

LANGUAGE: Hindi

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 155 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Uday Shankar Production

SET DESIGNER: K.R. Sharma

Restored in 2008 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the family of Uday Shankar, the National Film Archive of India, and Dungarpur Films. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

A great work of hallucinatory, homemade expressionism and ecstatic beauty, Uday Shankar’s Kalpana (Imagination) is one of the enduring classics of Indian cinema. Shankar, the brother of the great Ravi Shankar, was one of the central figures in the history of Indian dance, fusing Indian classical forms with western techniques. In the late 30s, he established his own dance academy in the Himalayas, whose students included his brother Ravi and future filmmaker Guru Dutt (who worked as an assistant on Kalpana). After the closure of the academy in the early 40s, Shankar started preparations on his one and only film, many years in the making.

Kalpana, with an autobiographical narrative of a dancer who dreams of establishing his own academy (starring Uday Shankar and his wife, the great Amala Shankar – the film also marks the debut of Padmini, who was 17 years old at the time), is one of the few real “dance films” – in other words, a film that doesn’t just include dance sequences, but whose primary physical vocabulary is dance. A commercial failure when it was released, the film is now regarded, justifiably, as a creative peak in the history of independent Indian filmmaking.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Kalpana has been digitally restored by the World Cinema Foundation at Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory using a combined dupe negative and a positive print held at the National Film Archive of India.

The combined dupe negative was badly damaged and marked by lines, tears, dirt, dust, white marks and poor definition. The restoration required a considerable amount of both physical and digital repair in order to recover the beauty of faces, movements and costumes, and to reduce the aforementioned issues. The original sound was digitally transferred from the combined dupe negative. Digital cleaning and background noise reduction was applied.

The restoration has generated a duplicate negative, new optical soundtrack negative for preservation as well as a complete back-up of all the files produced by the digital restoration.

Image: © Courtesy of National Film Archive of India

KUMMATTY

Director: Aravindan Govindan

WRITTEN BY: Aravindan Govindan

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Shaji N. Karun

STARRING: Ramunni, Master Ashokan, Vilasini Reema, Kothara Gopalkrishnan, Sivasankaran Divakaran, Vakkil, Mothassi, Shankar

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: India

LANGUAGE: Malayalam with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Color

RUNNING TIME: 90 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: General Pictures Corporation

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna in association with General Pictures Corporation and the Film Heritage Foundation at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory.

Funding provided by the Material World Foundation.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Restored in 4K using the best surviving element: a vintage 35mm print struck from the original camera negative and preserved at the National Film Archive of India. A second 35mm print with English subtitles was used as a reference.

Color grading was supervised by the film’s cinematographer Shaji N. Karun.

Special thanks to Ramu Aravindan.

LA FEMME AU COUTEAU

WOMAN WITH THE KNIFE, THE

Director: Timité Bassori

WRITTEN BY: Timité Bassori

EDITING: Guy Ferrant

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Ivan Baguinoff

STARRING: Timité Bassori, Danielle Alloh, Emmanuel Diaman, Tim Sory, Marie Vieyra

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Côte d'Ivoire

LANGUAGE: French with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 77 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Société Ivoirienne de Cinéma

Restored in 2019 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, created by The Film Foundation, FEPACI and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The 4K restoration of La femme au couteau was made from the 35mm original camera and sound negatives. The original camera negative was damaged by mold, dirt, and scratches, and therefore required an extensive amount of digital restoration. Director Timité Bassori supervised the picture grading.

LAW OF THE BORDER

HUDUTLARIN KANUNU

Director: Lüfti Ö. Akad

WRITTEN BY: Lüfti Akad, Yilmaz G Üney

EDITING: Ali Ün

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Ali Uğur

PRODUCER: Dadaş Film, shot in Yildiz Film Studios

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Ali Uğur

FROM: Dadaş Film

STARRING: Yilmaz Güney (Hidir), Pervin Par (Ayse, the teacher), Hikmet Olgun (Yusuf), Erol Taş (Ali Cello), Tuncel Kurtiz (Bekir), Osman Alyanak (Dervis Aga), Aydemir Akbas (Abuzer), Atilla Erg ün (Zeki, first lieutenant)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Turkey

LANGUAGE: Turkish with French and English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 74 minutes

PRODUCER: Dadaş Film, shot in Yildiz Film Studios

Restored in 2013 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, Dadaş Films, and the Turkish Ministry of Culture. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

Turkish cinema in sixties took place in a dream world. The movies of that era refused to look directly at Turkish society. Hudutların Kanunu, on which Yılmaz Güney met director Lütfi Ömer Akad, is one of the movies that changed this state of affairs. Akad’s genuine creative vision influenced Güney’s style as an actor: one can easily see the difference in Güney’s acting before and after Hudutların Kanunu. Akad’s influence was a positive one. . .

Güney’s natural performance marked a change in Turkish Cinema. This was the beginning of what would later be called “New Cinema” in Turkey. With its powerful cinematography and its direct and realistic depiction of social problems, Hudutların Kanunu is one of the early milestones of Turkish cinema. Given the manner of storytelling and the style of photography, one might almost say that Akad’s film is a Western.

Hudutların Kanunu depicts vital problems in the society of South East Turkey. Lack of education, no agriculture, and unemployment compelled people to live by the “law of the border” (Hudutların Kanunu) – in other words, smuggling. Hudutların Kanunu underlines the importance of education, which is the crucial element of socio-economical progress in third world countries. It also helps us to understand the reasons behind the ongoing, veiled war along Turkey’s South East border. Forty five years ago, Lütfi Ömer Akad was alerting Turkish society of the likely consequences if preventive measures are not taken in time. He alerted us with a great and lasting film, Hudutların Kanunu.

(Fatih Akin, May 2011)

Ömer Lüfti Akad’s Hudutların Kanunu comes as a revelation to first-time viewers – a work of great visual and dramatic force, of terrific purity and ferocity. It was made during the year that its star and co-screenwriter, Yilmaz Güney, made his own directing debut. And it’s not surprising for first time viewers to learn that this stunning collaboration marked a shift in Turkish cinema, and ushered in what became known as “the director generation.” Once again, the World Cinema Foundation’s advisory board member Fatih Akin has brought us a great and inspirational film.

(Kent Jones, May 2011)

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Hudutlarin Kanunu was made possible through the use a positive print provided by Nil Gurpinar, daughter of the film’s producer, and held by the Turkish Ministry of Culture.

As this print is the only known copy to survive the Turkish Coup d’Etat in 1980 – all other film sources were seized and destroyed – the restoration required a considerable amount of both physical and digital repair. The surviving print was extremely dirty, scratched, filled with mid-frame splices and sadly missing several frames. Although the film was shot in black and white, it was also printed on color stock resulting in significant decay. The restoration work produced a new 35mm dupe negative.

The World Cinema Foundation would like to specially thank Fatih Akin for recommending this title, and Ali Akdeniz and Nurhan Sekerci for facilitating the restoration process.

Image: © Courtesy of Nil Gurpinar - Dadaş Films

LE SÉNÉGAL ET LE FESTIVAL MONDIAL DES ARTS NÈGRES

Director: Paulin Soumanou Vieyra

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Senegal

LANGUAGE: French with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 28 minutes

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in collaboration with the Ministère de la Culture et du Patrimoine Historique de Sénégal – Direction du Cinéma. Restoration funded by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO―in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna―to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The 4K restoration was completed using a 16mm print preserved by the Direction du Cinéma in Senegal. With special thanks to Tiziana Manfredi and Marco Lena.

LIMITE

Director: Mário Peixoto

WRITTEN BY: Mário Peixoto

EDITING: Mário Peixoto

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Edgar Brazil

PRODUCER: Mário Peixoto

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Brutus Pedreira (themes from Satie, Debussy, Borodin, Stravinsky, Prokofiev)

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR: Rui Costa

FROM: Cinemateca Brasileira, São Paulo

STARRING: Olga Breno (Woman #1); Taciana Rei (Woman #2); Carmen Santos (The Whore); Mario Peixoto (The Man at the cemetery); Brutus Pedreira (Man #2 and the pianist); Edgar Brazil (The Man asleep at the cinema); Faciana Rei; Raul Schnoor

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Brazil

LANGUAGE: Silent

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 120 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Cinédia

PRODUCER: Mário Peixoto

Restored in 2010 by the Cinemateca Brasileira and Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, Arquivo Mario Peixoto, Saulo Pereira de Mello, and Walter Salles. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

Limite does not intend to analyse. It shows. It projects itself as a tuning fork, a pitch, a resonance of time itself. –Mário Peixoto

Then came the revelation of Limite, the first and only film by 21-year-old director Mário Peixoto. This was a film of transcendent poetry and boundless imagination. Once again, I found myself in a state of shock, not only because of the film itself, which was made in 1931 and forgotten for many years, but also for the evidence it bore, that of our creative diversity. –Walter Salles

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

Restored by the World Cinema Foundation at Cineteca di Bologna / L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory in collaboration with the Cinemateca Brasileira and Walter Salles.

Image: © Courtesy of Mário Peixoto Archive/ Cinemateca Brasileira

LOS OLVIDADOS

Director: Luis Buñuel

WRITTEN BY: Luis Buñuel, Luis Alcorira

EDITING: Carlos Savage

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Gabriel Figueroa

PRODUCER: Óscar Dancigers, Sergio Kogan, Jaime A. Menasce

MUSICAL DIRECTOR: Rodolfo Halffter

STARRING: Estela Inda, Miguel Inclán, Alfonso Mejía, Roberto Cobo, Alma Delia Fuentes

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Mexico

LANGUAGE: Spanish with English subtitles

COLOR INFO: B&W

RUNNING TIME: 80 minutes

PRODUCER: Óscar Dancigers, Sergio Kogan, Jaime A. Menasce

Restored by The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project in collaboration with Fundacion Televisa, Televisa, Cineteca Nacional Mexico, and Filmoteca de la UNAM.

Restoration funding provided by The Material World Foundation.

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

LOS OLVIDADOS was restored in 4K from the camera and soundtrack nitrate negatives preserved at Filmoteca de la UNAM. The film reels were scanned at UNAM laboratory and the soundtrack was digitized by Cineteca Nacional de México.

Special thanks to Gabriel Figueroa Flores for his supervision of the grading process.

The restoration work was carried out by L'Immagine Ritrovata in 2019.

LUCIA

Director: Humberto Solás

WRITTEN BY: Humberto Solás, Julio Garcia Espinosa, Nelson Rodríguez

EDITING: Nelson Rodríguez

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY: Jorge Herrera

PRODUCER: Raúl Canosa, Camilo Vives

PRODUCTION DESIGN: Pedro Garcia Espinosa, Roberto Miqueli

STARRING: 1895: Raquel Revuelta (Lucía); Eduardo Moure (Rafael); Idalia Anreus (Fernandina); 1932: Eslinda Nuñez (Lucía); Ramón Brito (Aldo); Flora Lautén (Flora); 196..: Adela Legrá (Lucía); Adolfo Llauradó (Tomás); Teté Vergara (Angelina)

COUNTRY OF PRODUCTION: Cuba

LANGUAGE: Spanish

COLOR INFO: Black and White

RUNNING TIME: 160 minutes

PRODUCTION COMPANY: Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC)

PRODUCER: Raúl Canosa, Camilo Vives

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC). Restoration funded by Turner Classic Movies and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project.

One of the abilities of cinema is to portray what a country is going through… it is about putting the country’s face on the screen, but it’s also about enlarging one’s vision of that specific place.

-- Walter Salles

ICAIC was born out of the victory of the Revolution. Those of us who were about to attempt to found a national film industry from scratch faced a set of problems that we had to resolve immediately. Our problem was a basic cultural dichotomy, as in Lenin’s thesis on national cultures. We had an elitist cultural tradition that represented the interests of the dominant class, and a more clandestine culture that had already received wide exposure; however, at some point, all artistic expression started to be converted into products of a consumer-oriented culture.

Because the elitist and the popular were so intimately tied, because petit bourgeois consciousness and influences from Europe and North America were so dominant, our general cultural panorama at the time of the Revolution was in fact a pretty desolate one. This was during the sixties, when the most important film movement was the French New Wave. Films like Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour (1959) or Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (1960) marked most of the subsequent decade. These influences alienated us from our indigenous cultural forms and from a more serious search for a kind of cultural expression consistent with national life and with the explosive dynamism of the Revolution. Yet this was a path we clearly had to travel. Anyone who picks up the tools of artistic activity for the first time is going to be vulnerable to outside influences.

With Lucía, I wanted to view our history in phases, to show how apparent frustrations and setbacks –such as the decade of the ’30s–led us to a higher stage of national life. Whenever you make a historical film, whether it’s set two decades or two centuries ago, you are referring to the present.

Lucía is not a film about women, it’s a film about society. But within society, I chose the most vulnerable character, the one who is more transcendentally affected at any given moment by contradictions and change.

-- Humberto Solás

NOTES ON THE RESTORATION:

The restoration of Lucía was made possible through the use of the original camera and sound negative and a third generation dupe negative provided by and preserved at the ICAIC.

The state of conservation of the negative was critical, due to advanced vinegar syndrome causing portions of the film stock to colliquate (melt) or stick together; the negative also appeared heavily warped and buckled, causing the image to lose focus throughout the film. Despite undergoing several weeks of drying and softening treatments, large portions of 8 (out of 18) reels could not be used. These sections were replaced with a second generation duplicate preserved by the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv since

the film had been distributed in East Germany in the late 1960s.

All the elements were wet-scanned at a 4K resolution to eliminate or reduce heavy scratches and halos. Additional documentation was used to confirm that the film had been shot on two different film stocks–Orwo and Ilford–and graded according to the time-period depicted in the film. A previously unscreened vintage print preserved at the BFI National Archive was used as a reference.

The original soundtrack was in fairly good condition, with the exception of uneven and inconsistent background noise detected in

the mix which required careful dynamic noise reduction.