Each organization involved brings unique experiences and skills to a project that spans an entire continent and will take years to complete. It is a remarkable example of international cooperation between those who want to educate and celebrate Africa through its cinema.

For the last in our series of interviews with key figures of the African Film Heritage Project, I sat down with Margaret Bodde of The Film Foundation, Cecilia Cenciarelli of Cineteca di Bologna, and Aboubakar Sanogo of FEPACI to discuss in more detail the individual efforts of their respective organizations in this ambitious and much-needed project.

Scorsese gave us an overview of the ethos behind AFHP, Iye explained the historical context of this important initiative. Now, we speak with those who travel the world and deal with the day-to-day aspects of achieving the AFHP’s grand vision.

• • •

Aboubakar Sanogo. (Courtesy of Ottawa Life)

Aboubakar, what is your role within FEPACI? What exactly does being North American regional secretary entail?

Aboubakar Sanogo (AS): To defend and promote the interests of African filmmakers anywhere in the world. I personally represent this region because I live in North America—representing Mexico, Canada and the USA —and The Film Foundation also happens to be based here!

FEPACI develops initiatives towards the production, distribution, and preservation of African cinema. I have personally taken a lead role here, drafting the plan for an African Archival Project. We plan to bring together archivists from all 54 African countries and bring together our knowledge to answer anything we might not know [about the continent’s archival infrastructure and conditions of individual archives].

We hope the AFHP will help mobilize and raise awareness within Africa [for our other initiatives] of our past, which filmmakers have addressed. The timing is critical, as […] we hope to help Africans explore political and cultural [alternatives] during the advent of a better Africa (a recent example of this, which occurred after this interview was conducted, is the historic peace being brokered between Ethiopia and Eritrea, which would end Africa’s longest war).

Can you tell us how the African Film Heritage project started? Who was behind it and when did you come onboard?

AS: The advisory board [for the World Cinema Project (WCP)] included at least two African filmmakers, one of them I believe was Souleymane Cisse. That’s when the idea of also preserving African films was mentioned. So [the WCP] started restoring African films in an ad hoc manner. About three of four years ago, FEPACI got involved through my work of rediscovering African film pioneers that look me to Cineteca di Bologna, where Scorsese was also working on the idea of the AFHP. We had a conversation with Cecilia about this and as part of FEPACI, I suggested we do something more ambitious on a continental level.

We could then work towards restoring the patrimony of African films and [restart] that conversation of our relationship [towards] our own cinema. At the time, FEPACI was launching the African Archival Project, which is ambitious and not only about restoration but also the creation of infrastructure [for film preservation] on the continent, and preserving what was already there in Africa. When you travel this vast continent to see the organization of it all… it’s not very good! At the time, we were on the ground ourselves to stop the destruction of archives [and the elements contained within] through inclement weather, human negligence and political intervention… there are all kinds of difficulties facing African archives.

It was natural that we teamed up to see if we could cast new light on some of the major works of African filmmakers. This was a vehicle to raise awareness of cultural heritage on the continent and around the world […] and begin lobbying governments to do something about this.

Margaret Bodde. (Courtesy of Zimbio)

Margaret, could you tell us how you became involved in the African Film Heritage Project?

Margaret Bodde (MB): Marty (Martin Scorsese) created the Film Foundation in 1990 and I started working for him the following year, helping him with what he had envisioned for the foundation. [We were] trying to raise funds and awareness for film restoration projects, mainly in the beginning at the US archives like the Library of Congress, the UCLA film and television archive, MOMA and the George Eastman Museum. Then, over the years, as Marty has a global view, he began to look outside the US. We then started restoring films from Britain, India, Italy… before there was digital, we helped the Academy (of motion pictures arts and sciences) restore Satyajit Ray’s Apu trilogy.

Marty’s always been enriched by cinema from around the world—he really began to see the need, as we all do, to really help some of these regions with very little in the area of archival infrastructure […] there’s not really anywhere for people to go to preserve their film, there’s no cinematheques or archives in many of these countries, and they don’t have much support for their national film patrimony.

What Marty does through the WCP, and what Cecilia is really spearheading, is this two-pronged effort to both preserve and restore films, [so[ that their survival in ensured, but also to distribute them and make them available for audiences who, in many cases, will be discovering these films [for the first time].

Cecilia Cenciarelli. (Courtesy of Festival Internacional del Nuevo Cine Latinoamericano)

Cecilia, how did you and Cineteca di Bologna become involved with the project?

Cecilia Cenciarelli (CC): We started developing a relationship with the Film Foundation in the early 2000s and we started with mostly restoring Italian cinema […] I’ve been working at the Cineteca for 18 years and I naturally became involved with [the world cinema project] in 2007. The AFHP is just another extension of the world cinema project. The peculiarities we [dealt with when we] were discovering and restoring with the WCP led us to understand [that], clearly, there were going to be specific dangers and issues and challenges linked to the African continent and diaspora that needed special attention.

What are your personal relationships with African cinema before this project began to take shape? had of either you ever seen African film or been aware of the issues were facing it before you collaborated together?

MB: Cecilia has a much deeper understanding of African Cinema in general, but through the WCP we had already restored a few of the seminal African films—Ousmane Sembene’s films Black Girl and Borom Sarret, and North African films like Al Momia and Alyam, Alyam. There was this realization, through our experiences with those films, of the great need for preservation [through Africa].

CC: When I started at the Cineteca, [they] were hosting the first significant festival of films from the Mediterranean countries, so to speak. It was mostly North Africa where the most legendary filmmakers [of that region], mostly Egyptian but also Algerian, came from. Because of [what] the collections [had amassed] over the years, through chances and opportunities, we were always encouraged, as a film archive, to look at the richness of African cinema. We programmed it with FESPACO twice [and[ I’ve traveled to Africa, mostly North Africa, a bit…

The thing with African Cinema that is hard to narrow down, is that every single time you are exposed to a film, you realize how you’re just scratching the surface—there’s an understanding that we can access whatever we want through the internet, but [also] a misunderstanding we can [just automatically] reach out to every culture [and immediately develop a relationship with it], which is not true at all! I think it’s hard to claim to know a lot about African cinema [right now], which is just one of the reasons this project is so important.

Cineteca di Bologna, (Courtesy of Bologna da Vivere).

So the Film Foundation and Cinetca di Bologna have a long-standing relationship, but since the AFHP began what has it been like for you both, collaborating with UNESCO and FEPACI?

MB: FEPACI already had preservation initiatives [underway], as this is a core mission for them, and we basically came together with [common] purpose.

CC: Yeah, the AFHP came together at a very good time. It’s my understanding, discussing with Aboubakar and FEPACI, we were developing this project and starting a conversation right at the moment when FEPACI launched an archival survey as a priority, for the first time in its history. They wanted to really start looking into the state of the archives [that might hold African films] and what could be done to improve infrastructure, and finding out what were the holdings of these archives.

It was important to us to let the african filmmakers, scholars and historians guide us through the project. I don’t think a project like the AFHP could have been done without such prominent presence and initiative of an African organization.

MB: Once we get to the distribution of these films, through their ‘General History of Africa’ project, UNESCO already has their own support, infrastructure and relationships with all [the] key people in those regions. FEPACI and the Film Foundation are [leading] the actual preservation and restoration work with the [various] archives and the filmmakers, but UNESCO will be particularly helpful when we complete the restorations and seek to get them exhibited and distributed widely in Africa.

Le Vent des Aures, one of the films being restored by the AFHP. (Courtesy of Festival de Cannes)

What are these four organizations doing to ensure that, once the 50 african films have been located and restored, they will be seen by African audiences as the priority? This is a continent with less movie theatres and less reliable internet for streaming options than you may have in Asia or the Western world.

CC: This is a very crucial point for us, this is a priority – getting the films back to the African audiences – and we are aware of that. We are still in the first steps of the project, at the restoration level. […] You’re right, there are very few movie theatres, but there are traveling theaters. It’s the reality that exists and we really rely on our African partners to know the best ways to reach out to everything that exists. UNESCO has different programs in place and we’re going to be relying on their experience, as well as FEPACI.

Aboubakar, What do you feel are the primary problems that African Cinema currently faces? a lack of readily available education and resources for audiences and future filmmakers? or is the lazy preconceptions that global audiences have about africa, which possibly feeds into financial support of african films?

AS: Everything you’ve just mentioned, and many more! [laughs] Education helps! There are initiatives […] striving towards the professionalization of the African film sector, that train Africans across the world. We need Africans to go and be trained abroad, like I was.

Part of the problem, maybe the biggest problem, is funding. Those who made films in the 1970s and ’80s have stopped making films because they’re not able to find funding. People like Souleymane Cisse and Med Hondo, for Christ’s sake! Many filmmakers cannot get [the] resources they need because they’re too ambitious! They have to scale down those ambitions. Things are extremely difficult for the new generation, too, who have new ideas and want to revolutionize cinema.

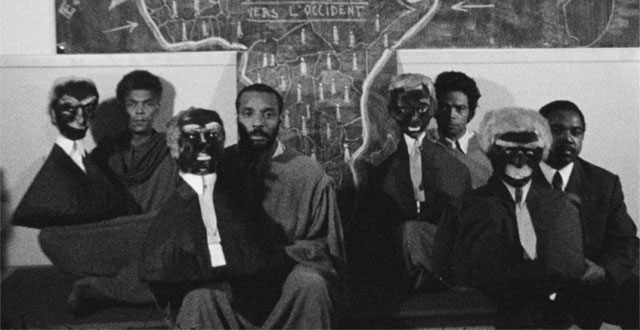

Med Hondo’s Soleil O [1969]. (Courtesy of CNN)

Can you give us an idea of the scale of what the African Film Heritage Project is undertaking? Finding films from 54 different countries, which haven’t necessarily been protected and preserved…

MB: [For the Film Foundation,] Cecilia is really “Our Man in Havana”! (laughs)

CC: (laughs) that’s so kind! [We encounter] quite a specific issue when [we] go to the locations. This is why, in the mission statement published in the press release, the location of the elements is [mentioned] – it’s very complex when we [have, in the past,] restored films from countries like Armenia, Turkey, Sudan, or Brazil [as opposed to from countries like the US] – there’s always that element of not being absolutely sure of where you’re going to find the best negatives.

[With Africa] it’s a very different situation, which can be traced back to how [many of] these films were produced, with a lack of infrastructure, leading African filmmakers to Europe to develop their prints! These elements (original negatives) are never found in Africa, they’re always in European archives and laboratories. If it’s in a public archive, you have a better chance of locating it quicker, [but] archives like Cineteca di Bologna [don’t] often have enough funds to catalog everything we have. Often there are gray areas in the catalogs of every single archive. When it’s a private laboratory, things get even more complicated because they shut down, the collections pass into different hands, they’re auctioned sometimes, sold or acquired [by other people]. The information about a lot of these obscure films, that haven’t been enquired about for a long time, is a lot harder to find […] than one might expect.

The first thing we want to do—which is very ambitious‚—if we’re investigating a particular film by a particular filmmaker, [is] try and gather as much information as we can not only about the film, but also the other films by that filmmaker that might be in the same [archive or laboratory]. What we would like to have is a very open, shared database […] These [films] are part of African culture and history, and they should be stored in Africa. But all this relevant information [about the filmmakers and the location of their films] is scattered all around the world [so it’s tricky trying to achieve this goal, but having a global database is going to help].

We’re doing this with [the] full respect that is due to the filmmakers. We don’t just locate and restore these films without informing the filmmakers and getting their authorization. This is something FEPACI is leading the way in, and can put us in contact with the filmmakers and introduce us. Some do not have access to the internet, so we have to go and explain exactly what we are going to do in a technical sense – there may be multiple cuts of one film, some of them censored, or re-dubbed, so we always try as much as possible to find out everything we can about a film, and who among those involved is still alive, who has the most expertise regarding each individual film, who has worked on this film the most before us… it’s important to bring all these people together [to make the best restoration possible that is true to the original vision of the films]. I could talk about just this part of process for hours! [laughs]

Morocco’s Trances [1982], a personal favorite of Scorsese’s. (Courtesy of Criterion)

Who exactly is deciding which films should be located and restored? Are there certain criteria for determining which films will be preserved? Why is one film more deserving than another in the eyes of your organizations?

MB: The list is being vetted and put together by FEPACI, a consortium of scholars and filmmakers and producers. They really are the best-equipped to assess the cultural, historic and artistic importance of these films. The goal is to be as Pan African as possible, to be drawing films from every region because most of the African cinema that the west is familiar with is usually north or western.

As they put this list [of fifty films] together, they want to be as representative of the continent’s fifty-four countries as possible. That’s a shifting process- we have a database, and currently have five or six films we’re actively pursuing right now. The list is continually being updated and vetted with information that FEPACI is coming across in discussions with people from different African countries.

AS: This is really being led by FEPACI. We have a committee of archivists and historians who have a profound knowledge of African Cinema. We are a Pan African federation, which of course means trying to involve all five regions of the continent, and of course the diaspora- the sixth region! So there is the geographic criteria to consider.

Then there is the historiographic criteria – we are interested in the hundred-year period of 1889 to 1989, from the very first Edison experiments onwards. We are looking at films made by Africans within this period. Most people know the post-independence era, and filmmakers like Sembene, but we are also interested in the colonial period. Africans were making films even during this time, from Tunisia and Morocco to Guinea and beyond.

Part of the project for us is to be able to have a comprehensive history of African cinema in the Braudelian sense. (Editor’s note: Fernand Braudel was a French historian who developed the idea of the longue durée, which looked at historical events and how long-standing institutions were far more responsible than immediate effects. For example, this theory attests that a conflict isn’t caused primarily by recent catalytic events, but by deep-seated attitudes. So approaching a history of African cinema would not just look at how it was shaped following independence, but how centuries of colonial oppression informed the motivations of African filmmakers and their ancestors)

These filmmaker’s works may be hidden away in archives, and many would not have heard of them, but they have played a major role in our history and in world cinema in general [and through the AFHP, we hope to correct that lack of awareness].

One of my trips to Cineteca di Bologna centred around a Tunisian filmmaker (Albert Samama Chikly) who was active from 1903! He captured World War One, earthquakes in Italy… he was an immense figure in early cinema but he is hardly mentioned. That is the kind of filmmaker we talk about, and hosted a small retrospective of his works, which was a revelation to film historians! This is just one example of Africa’s contributions to film history.

Ousmane Sembene’s Borom Sarret [1963], one of the earliest examples of post-independence African cinema. The AFHP aims to look well beyond this era of film. (Courtesy of Festival de Cannes)

CC: A question we get asked a lot is, “why fifty films?”. It could be five hundred, or five thousand! In no way will the fifty films summarize the richness of African film. It was a [starting point], and underlines the need for this kind of project—something mammoth and ambitious that will probably take a [long time] to accomplish. The list [of films] is being revised according to several strands—we’re trying to trace back to the pioneer [African] filmmakers, as well as the Masters and Genre films. We’re trying to find the right balance [of] good representation of all the voices of Africa. We always come across information we didn’t know when we started this—if we find out about a particular film that’s in danger because of weather conditions or preservation issues, we can take immediate action and restore them quickly, otherwise, we lose films. They joke in the film labs that they are very much like the ER!

MB: With the WCP titles and AFHP titles, most of these films were made independently. [There’s] not quite a clear-cut path to get access to the negatives. Cecilia and her team face a years-long process of researching where these elements are located, negotiating with those who have them to let us preserve and restore the films… it’s a time-consuming process. We look at the list of fifty films, but it’s not like we’re trying to scale Everest in one go—we’re taking it a little bit at a time, but when we know it’s going to take many years because we need to raise funds to do this properly, we feel [OK with that because] the project warrants such investment of time and resources to accomplish.

Aboubakar and Scorsese. (Courtesy of YouTube)

There hasn’t been any attempt of this kind, on this scale, before. Why do you think organizations haven’t stood up for African cinema in this way until now?

AS: There isn’t a model like [the one for the AFHP] anywhere on the planet! Martin has his team in New York, another in Los Angeles, another in Bologna, our team at FEPACI, and UNESCO, of course… all the main stakeholders brought together to create a structure for advocating for African cultural heritage.

Martin really is one of the blessings of cinema, a film historian himself, a cinephile and one of the most open-minded filmmakers I’ve ever met, taking influences regardless of where they come from. he has a desire for what is not firmly part of the Euro-American canon. I really admire him for this, and […] this makes him indispensable for us.

MB: It’s a little bit mad to think can do this! It’s very inspiring to work with Scorsese. One of the things I most admire about him is that the word “no” is not in his vocabulary! He the kind of person where if he feels something, he wills it to happen. This initiative, the WCP… they needed to be done, so he just did it! There’s no business plan with him- [he says] “figure out how to get it done, let’s get to work and everything else will follow!”. In the short span of ten years, thirty-two films have already been restored, preserved and distributed through the World Cinema Project. The Film Foundation has done this with over eight hundred films, helping others in many ways. He’s not just a brilliant filmmaker but a passionate advocate. With him, it all comes from the heart. He inspires our work, so we don’t want to go back to him and say “it can’t be done”.

CC: Lots of people ask whether Scorsese’s involvement is just being a name behind this, but I’ve been astonished to see how he could find the time and interest to be constantly involved with all of this work. It’s an incredible privilege to encounter such a spirit and such a vision.

Ivorian film La Femme au Couteau [1969], one of the films being restored by the AFHP. (Courtesy of Mubi)

This project is very much about the past, but regarding the future, do you believe there are any filmmakers we should be keeping an eye on within the continent? What is improving? What needs to be addressed within this new generation?

AS: It would be a mistake to consider this a project about the past. In fact, it’s about a future that is aware of its past. Part of the problem is there is still a kind of rupture [concerning] intergenerational transmission. For example, no film school worthy of its name in Europe or America would train filmmakers without bringing up Eisenstein or Griffith or Orson Welles or German expressionism…

That very fundamental education that every filmmaker should know!

AS: Right! The foundation from which new ideas can come. But today in Africa, it’s possible to go to a film school and not see [a film by] Sembene or Med Hondo!

It’s unbelievable!

AS: It is. This project is about allowing the new generation to re-appropriate that. Cinema belongs to all of us—regardless of where you come from, you can be touched by the films of others, but should be exposed to that which was created domestically. You should be able to have it as part of your vocabulary – we want to reinsert African films into the vocabulary of those African filmmakers, and filmmakers from around the world. It’s the heart of the AFHP.

Who are some figures within African Cinema you hope will become part of the popular conscience as the restoration rolls out? Who should audiences really know about?

AS: So many – [to name a few,] Sarah Maldoror, Ahmed Bouanani, Jean-Pierre Dikongué Pipa, John Akomfrah, Flora Gomes, Timite Bassori… Of course, we shouldn’t forget the women filmmakers! Safi Faye and many others! The pantheon is broad, but we have a narrow view right now, and need to expand it.

As someone who loves African Cinema, thank you all for your continued efforts. I speak for a lot of people when I say that we’re grateful that this project even exists.

MB: We’re glad you’re shining a light on it! The more we can get the word out, the more people will reach out and help us.

• • •

Aboubakar Sanogo is FEPACI’s North America Regional Secretary. You can find out more about FEPACI’s work here.

Magaret Bodde is executive director for The Film Foundation. You can find out more about their work here.

Cecilia Cenciarelli is Head of Research at Cineteca di Bologna. You can find out more about their work here.

You can read the rest of the interviews from this series of interviews focused on the African Film Heritage Project, in which we spoke with Martin Scorsese and UNESCO’s Ali Moussa Iye.