The festival’s fiction film highlights include Michael Tyburski’s “The Sound of Silence,” starring Peter Sarsgaard and Rashida Jones, Noble Jones’ “The Tomorrow Man,” starring John Lithgow and Blythe Danner; Mary Harron’s “Charlie Says” with Harron attending on May 4; Alex Thompson’s SXSW Audience Award winner “Saint Francis”; and Guy Nattiv’s “Skin,” starring Jamie Bell, Danielle Macdonald, and Vera Farmiga.

News

Announcing the FOCAL Awards 2019 Winners

FOCAL International are proud to announce the winners from last night’s FOCAL Awards ceremony, held at the Troxy in London. The trade association have given 14 awards to productions making bold and compelling use of archival footage, as well as three personnel awards recognising the work of practitioners, researchers and companies and two awards celebrating restoration and preservation. Julien Temple also received the Lifetime Achievement Award, which came with a few surprises in the form of a video message from Keith Richards, and Wilko Johnson handing Julien his award on stage. The acclaimed filmmaker went on to thank all the talented archive producers with whom he’s worked and advocated for the power of archival footage to tell immersive stories. Guests were entertained by the charming wit of comedian Zoe Lyons, as the FOCAL Awards 2019 ceremony host.

Here are the winners for each category;

Footage Person of the Year

Jane Fish, Imperial War Museums

Footage Company of the Year

Screenocean

Best Archive Restoration & Preservation Project

Joe 90

Best Archive Restoration & Preservation Title

Pixote

Best Use of Footage in a History Production

The Scientist, The Imposter and Stalin: How to Feed the People (Le savant, l’imposteur et Staline: Comment Nourrir le Peuple)

Best Use of Footage in an Entertainment Production

Mr. SOUL!

Best Use of Footage in a Sports Production - TIE

Bobby Robson: More Than a Manager & Momentum Generation

Best Use of Footage on Innovative Platforms

British Pathé TV

Best Use of Footage in an Arts Production

Kulenkampff’s Shoes

Best Use of Footage in a Factual or Natural World Production

Under the Wire

Best Use of Footage in a Music Production

John and Yoko: Above Us Only Sky

Best Use of Footage in a History Feature

Apollo 11

Best Use of Footage in Advertising or Branded Content

WWF – Fight For Your World

Best Use of Footage in a Short Film Production

A Night at the Garden

Best Use of Footage in a Cinematic Feature

They Shall Not Grow Old

Student Jury Award for Most Inspiring Use of Archive

Mr. SOUL!

Jane Mercer Researcher of the Year Award

Peter Scott for A Dangerous Dynasty: House of Assad

FOCAL International would like to extend their congratulations to all of the awardees, nominees and attendees of this year’s awards, as well as our many jurors and sponsors, without whom the delivery of such an important and vibrant competition.

The FOCAL Awards will return in 2020, and submissions will open later this year. Expressions of interest ahead of time are welcome and encouraged. The team can be contacted through awards@focalint.org

About FOCAL International Ltd

FOCAL International (Federation of Commercial Audiovisual Libraries) is a professional not-for-profit trade association formed in 1985. It is fully established as one of the leading voices in the industry which represents the footage and content libraries in over 30 countries, the archive producers, researchers, consultants and facility companies. The FOCAL International Awards are the organisation’s flagship event and exists to champion the use of archive footage in the creative industries as well as the work and contributions of many of its talented members.

www.focalint.org www.focalintawards.com

Cannes Classics 2019

The 25 years of La Cité de la peur, a Midnight Screening of The Shining presented by Alfonso Cuarón, the 50 years of the mythical Easy Rider in the company of Peter Fonda, Luis Buñuel in the spotlight with three films, the attendance of Lina Wertmüller, the Grand Prix of 1951 Vittorio De Sica's Miracle in Milan, a final salute to Milos Forman, the first Japanese animated film in color, the World Cinema Project and the Film Foundation of Martin Scorsese, documentaries about cinema and History, masterpieces known and rare films in restored version from countries rarely honored, this is the new edition of Cannes Classics—the first section dedicated to heritage cinema ever created in a major festival.

The majority of the films will be screened at Buñuel Theater, Salle du 60e or at the Cinéma de la Plage, all presented by major players in the film heritage: directors, artists or restoration managers.

The 50 years of the mythical Easy Rider

Presented half a century ago on the Croisette, in Competition at the Festival de Cannes, the film won the Prize for a first work. Co-writer, co-producer and lead actor, Peter Fonda will be in Cannes at the invitation of the Festival to celebrate this anniversary.

Easy Rider (1969, 1h35, USA) by Dennis Hopper

Restored in 4K by Sony Pictures Entertainment in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna. Restored from the 35mm Original Picture Negative and 35mm Black and White Separation Masters. 4K scanning and digital image restoration by Immagine Ritrovata. Audio restoration from the 35mm Original 3-track Magnetic Master by Chace Audio and Deluxe Audio. Color grading, picture conform, additional image restoration and DCP by Roundabout Entertainment. Colorist: Sheri Eisenberg. Restoration supervised by Grover Crisp.

Midnight Screening of The Shining

The ultimate horror film for an event screening presented by Mexican director Alfonso Cuarón.

The Shining by Stanley Kubrick (1980, 2h26, UK / USA)

A Presentation of Warner Bros. The 4K remastering was done using a new 4K scan of the original 35mm camera negative. The mastering was done at Warner Bros. Motion Picture Imaging, and the color grading was done by Janet Wilson, with supervision from Stanley Kubrick’s former personal assistant Leon Vitali.

The 50 years of La Cité de la peur

The cult comedy of comic group Les Nuls will be screened at Cannes Classics au Cinéma de la Plage upon the occasion of the 4K restoration of the film for its 25th anniversary with Alain Chabat, Chantal Lauby and Dominique Farrugia in attendance.

La Cité de la peur, une comédie familiale (1994, 1h39, France) by Alain Berbérian

Presented by Studiocanal. A restoration by Studiocanal and TF1 Studio . 4K scanning 16bits from the original negative 35mm on Lasergraphics director. The pre-calibration was done in a projection room equipped by a 4k projector 4k Christie Laser by Pascal Bousquet and additional work of filtering, dusting was done to compensate the imperfection due to the age of the film. Optical illusion composited on DI on Flame to remain close to the quality of the original negative. Calibration validated by Laurent Dailland, director of photography. Original digital sound was used without modification. Work of remastering done by VDM Laboratory.

Luis Buñuel in the spotlight with three films

Three films by Mexican director and screenwriter, with Spanish origin, will be shown this year.

Los Olvidados (The Young and the Damned) (1950, 1h20, Mexico) by Luis Buñuel

Presented by the World Cinema Project. Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project at L’Immagine Ritrovata in collaboration with Fundación Televisa, Cineteca Nacional Mexico, and Filmoteca de la UNAM. Restoration funding provided by The Material World Foundation.

Nazarín (1958, 1h34, Mexico) by Luis Buñuel

Presented by Cineteca Nacional Mexico. 3K Scan and 3K Digital Restoration from the original 35mm image negative (preserved by Televisa) and prints positive materials from Cineteca Nacional. Restoration made and financed by Cineteca Nacional Mexico. Mastered in 2K for Digital Projection.

L'Âge d'or (The Golden Age) (1930, 1h, France) by Luis Buñuel

Presented by La Cinemathèque française. A 4K restoration of The Golden Age was done by la Cinemathèque française and le Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Experimental cinema’s department, at Hiventy Laboratory for the image and at L.E. Diapason’s studio for the sound, using the original nitrate negative, original sound and safety elements.

Tribute to Lina Wertmüller

The first woman director ever nominated as a director at the Academy Awards in 1977 for Pasqualino Settebellezze, Lina Wertmüller will introduce the film with lead actor Giancarlo Giannini in attendance.

Pasqualino Settebellezze (Seven Beauties) (1975, 1h56, Italy) by Lina Wertmüller

Presented by Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia - Cineteca Nazionale. Restored by Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia - Cineteca Nazionale with the support of Genoma Films and Deisa Ebano from the original 35mm picture and optical soundtrack negative made available by RTI S.p.A. Digital scanning and restoration work carried out by Cinema Communications in Rome.

The 1951 “Palme d'or”

The Palme d'or was created in 1955 but the Grand Prix awarded to Miracle in Milan by Vittorio De Sica was the equivalent.

Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan) (1951, 1h40, Italy) by Vittorio De Sica

Presented by Cineteca di Bologna. Restored by Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and Compass Film, in collaboration with Mediaset, Infinity TV, Artur Cohn, Films sans frontières and Variety Communications at L'Immagine Ritrovata laboratory. 4K Scan and Digital Restoration from the original 35mm camera negative and a vintage dupe positive. Colour grading supervised by DoP Luca Bigazzi.

Milos Forman

A devotee of the Festival de Cannes, a former President of the Jury, a director with several lives, Milos Forman passed away one year ago. The restoration of his second film and a documentary will give us the opportunity to pay our tribute and remember him.

Lásky jedné plavovlásky (Loves of a Blonde) (1965, 1h21, Czech Republic) by Milos Forman

A presentation of the Národní filmový archiv, Prague. 4K digital restoration based on the original camera done by the Universal Production Partners and Soundsquare in Prague, 2019. The donors of this project were Mrs. Milada Kučerová and Mr. Eduard Kučera. Restored in partnership with the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival and the Czech Film Fund. French distribution: Carlotta Films.

Forman vs. Forman (Czech Republic / France, 1h17) by Helena Trestikova and Jakub Hejna

Presented by Negativ Film Productions, Alegria Productions, Czech Television, ARTE. A powerful documentary that recounts with emotion the career of director Milos Forman, from the Czech New Wave to Hollywood. Oscars, politics and political upheavals for a life in the service of cinema.

All the restored films of Cannes Classics 2019

Toni by Jean Renoir (1934, 1h22, France)

Presented by Gaumont. First digital restoration in 4K presented by Gaumont with the support of the CNC. Restoration done by L’image retrouvée in Bologna and Paris.

Le Ciel est à vous (1943, 1h45, France) by Jean Grémillon

Presented by TF1 Studio. Restaured version in 4K using two intermediate and a duplicate done by TF1 studio, with the support of the CNC and Coin de Mire cinéma. Digital and photochimical work done by L21 laboratory.

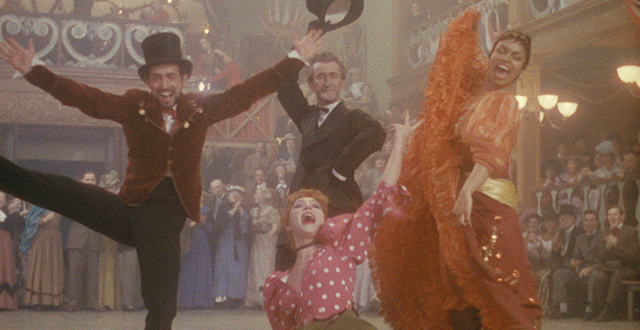

Moulin Rouge (1952, 1h59, UK) by John Huston

Presented and restored by The Film Foundation in collaboration with Park Circus, Romulus Films and MGM with additional funding provided by the Franco-American Cultural Fund, a unique partnership between the Directors Guild of America (DGA), the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), the Société des Auteurs, Compositeurs et Editeurs de Musique (SACEM), and the Writers Guild of America, West (WGAW). Restored from the 35mm Original Nitrate 3-Strip Technicolor Negative. 4K scanning, color grading, digital image restoration and film recording by Cineric, Inc., New York. Colorist: Daniel DeVincent. Audio restoration by Chace Audio. Restoration Consultant: Grover Crisp.

Kanal (They Loved Life) (1957, 1h34, Poland) by Andrzej Wajda

Presented by Malavida, in association with Kdr. Scanned, calibrated and restored in 4K under the artistic supervision of Andrzej Wajda and Jerzy Wójcik, second DOP, and regular collaborator of Wajda (Ashes and Diamonds) and one of the greatest Polish DOP. Technical supervision: Waldermar Makula. 4k Scan from the original negative, image and sound. Producted by Studio Filmowe Kadr with the participation of Filmoteka Narodowa. French distribution: Malavida. International Sales: Studio Filmowe Kadr.

Hu shi ri ji (Diary of a Nurse) (1957, 1h37, China) by Tao Jin

Presented by IQIYI et New Ipicture Media co., ltd (NIPM). 4K Scan and 3K Digital Restoration from the original 35mm print positive materials mastered in 2K. Restoration financed by IQIYI & NIPM, and made by L’Immagine Ritrovata (Italy) and Laser Digital Film SRL (Italy).

Hakujaden (The White Snake Enchantress) (1958, 1h18, Japan) by Taiji Yabushita

Presented by Toei Animation Company, ltd., Toei company, ltd. et and National Archive of Japan. The project celebrates the 100th year anniversary for the birth of Japan animation and 60th anniversary for the original theatrical release in 1958.

4K scan and restoration from the original negative, 35mm print, tape materials, and animation cels by Toei lab tech co., ltd. et Toei digital center are carried out. The restored data is stored in 2K.

125 Rue Montmartre (1959, 1h25, France) by Gilles Grangier

Presented by Pathé. 4K Scan and 2k restoration, using the original safety negative (negative image, intermediate and negative optique sound) Work done by Eclair laboratory for the image and L.E Diapason (Léon Rousseau) for the sound part. Restored with the support of the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC).

A tanú (The Witness) (1969, 1h52, Hongrie) by Péter Bacsó

The original uncensored version presented by the Hungarian National Film Fund – Film Archive. The film was restored in 4K using the original camera negative and outtakes, the only existing uncensored positive print and the original magnetic sound. The restoration was carried out at the Hungarian Filmlab. The digital colour grading was supervised by Tamás Andor (HSC, Hungarian Society of Cinematographers).

Tetri karavani (The White Caravan) (1964, 1h37, Georgia) by Eldar Shengelaia and Tamaz Meliava

Presented by Georgian National Film Center. 4K Scan from 35mm, digital restoration (color, grading, stabilization). Restoration financed by the Georgian National Film Center, the restoration made by National Archives of Georgia.

Director Eldar Shengelaia in attendance.

Plogoff, des pierres contre des fusils by Nicole Le Garrec (1980, 1h48, France)

Presented by Ciaofilm. Restored in 2k from the original negative 16mm image. Sound restoration from the 16mm magnetic. Work done by Hiventy laboratory under the supervision of Ciaofilm and Pascale Le Garrec, with the help of the CNC, Région Bretagne and the Cinemathèque de Bretagne. Distributed by Next Film Distribution.

Director Nicole Le Garrec in attendance.

Caméra d’Afrique (20 Years of African Cinema) by Férid Boughedir (1983, 1h38, Tunisia / France)

Presented by the CNC. Restoration: Laboratory of the CNC. 2K scan from the original 16mm image negative. Sound restoration : Hiventy. This movie fits into the restoration scheme initiated by L’Institut français and the CNC, supervised by the commitee for the African cinematographic heritage. Right-holders: Marsa film. French Distribution: Les Films du Losange.

Director Férid Boughedir in attendance.

Dao ma zei (The Horse Thief ) (1986, 1h28, China) by Tian Zhuangzhuang and Peicheng Pan

Presented by Xi’An Film Studio. 4K Scan and 4K 48 fps digital restoration from the 35mm original camera negative. Restoration financed and made by China Film Archive.

Director Tian Zhuangzhuang and Cinematographer Hou Yong in attendance.

The Doors (Les Doors) (1991, 2h20, USA) by Oliver Stone

Presented by Studiocanal, in partnership with Paramount, Lionsgate and Imagine Ritrovatta. Restored in 4k, initiated and supervised by Oliver Stone from the original negative, scanned in 4k 16 bits on ARRISCAN at Fotokem US. Restoration managed by Imagine Ritrovatta in Italy. Calibrated work supervised by Oliver Stone. Immersive soundtrack thanks to the Atmos mix created by Formosa Group, Hollywood, under the supervision of Dolby and original mixers of the film Wylie Stateman and Lon Bender. The movie can be seen in 7.1 and 5.1. Remastered 4K now available in 4K Cinema, UHD Dolby Vision and Atmos.

Documentaries

Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound (USA, 1h34) by Midge Costin

Presented by Dogwoof and Cinetic Media.

The biggest directors and artists make us immerse in the history and impact of sound in cinema: Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Barbra Streisand, John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Patty Jenkins, Robert Redford, Ryan Coogler, David Lynch, Sofia Coppola, Christopher Nolan, Ang Lee, Walter Murch. A rich, fascinating and essential documentary.

Les Silences de Johnny (55mn, France) by Pierre-William Glenn

Presented by les films du Phœnix in coproduction with Ciné+.

A personal and moving portrait of actor Johnny Hallyday by great cinematographer, director and friend of Johnny's Pierre-William Glenn.

La Passione di Anna Magnani (1h, Italy / France) by Enrico Cerasuolo

Presented by les Films du Poisson and Zenit Arti Audiovisive.

The destiny of legendary actress Anna Magnani through archive footage, often unpublished. To dive into the history of Italian cinema.

Cinecittà - I mestieri del cinema Bernardo Bertolucci (Italy, 55mn) by Mario Sesti

Presented by Erma Pictures in collaboration with Cinecittà Luce.

A presentation of Erma Pictures in collaboration with Cinecittà Luce.

The last interview of the Master Bertolucci who recalls his work with precision, delicacy and philosophy. A movie lesson.

EXCLUSIVE: Nina Menkes' QUEEN OF DIAMONDS Restoration Gets A New Trailer From Arbelos

J Hurtado

A new distributor on the block is making big waves with their acquisition and restorations of classic film from around the world. From the ashes of Cinelicious Pics has risen Arbelos, who've already worked on stunning restorations of Dennis Hopper's The Last Movie and Bela Tarr's Satantango, and among their many exciting upcoming projects we now have Nina Menkes' '90s feminist touchstone, Queen of Diamonds to look forward to.

Queen of Diamonds will open with a run at BAM in New York on April 26th, followed by an LA opening on June 15th. Both locations will have opportunities to engage with Menkes in the form of Q&A's as well as the chance to attend Menkes' Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression talk on select dates. This is a unique opportunity that anyone within driving distance of these events should definitely put on their calendar.

Arbelos has given us an exclusive first look at the restoration trailer, you will find it below along with a couple of sample stills from the film.

Nina Menkes' QUEEN OF DIAMONDS New 4K Restoration

Opens NYC on 4/26 at BAM

Opens LA on 6/15 at UCLA Film & Television Archive

An Arbelos release and co-presented with the Eos World Fund. New restoration by the The Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the George Lucas Family Foundation.

From Friday, April 26 through Thursday, May 2, BAM presents a brand new restoration of Nina Menkes’ radical, feminist feature, Queen of Diamonds (1991). Menkes will appear in person following the 7pm screening on April 26; she will also present her celebrated talk Sex and Power: The Visual Language of Oppression, followed by a Q&A, on April 27.

In one of the most jarringly original independent films of the 1990s, a disaffected blackjack dealer, (played by the director’s sister Tinka Menkes), drifts through a neon-soaked dream vision of Las Vegas and experiences a series of encounters alternately mundane, surreal, and menacing, while death and violence hover ever-present in the margins. Awash in lush, hallucinatory images, Queen of Diamonds is a haunting study of female alienation with intellectual heft and formal rigor, from a filmmaker whose work can be compared to Akerman, Fassbinder, and Lynch, but with a unique, singular vision all her own.

Queen of Diamonds will also be presented, along with Menkes’s nightmarish true-crime feature The Bloody Child, by the UCLA Film & Television Archive at the Billy Wilder Theater in Los Angeles on June 15th.

Based on her viral Filmmaker Magazine article “The Visual Language of Oppression: Harvey Weinstein Wasn’t Working in a Vacuum,” Menkes’ Sex and Power examines the ways formal shot design is gendered. Analyzing a series of film clips by major filmmakers—including Scorsese, Welles, Spike Lee, and many others—Menkes shows how traditional cinematic language underlies and supports sexual assault, harassment, and employment discrimination against women. The presentation has appeared at Sundance, Cannes, and the AFI International Film Festival, and is currently being made into a feature length documentary. Maria Giese, who instigated the historic ACLU and EEOC investigations against the Hollywood studios’ Title VII violations, will moderate a discussion following the talk.

Nina Menkes is the writer, director, and cinematographer of six feature films, including Magdalena Viraga (1986), Phantom Love (2007) and Dissolution (2012). Her films have shown widely at major festivals, including Sundance, Locarno, the Berlinale and she has had retrospectives internationally. Menkes has received American Film Institute and Guggenheim Fellowships, and was an artist-in-residence under the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Program. She is currently a faculty member at California Institute of the Arts, and developing two new projects: Minotaur Rex, a horror-drama about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, (produced by Eos World Fund), and Heatstroke a psychological thriller about two sisters set in Cairo and LA (produced by Marginalia Pictures).

"Nina Menkes is one of the most provocative and challenging artists in film today.”

Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times

“Queen of Diamonds may become for America in the 90’s what Jeanne Dielman was for Europe in the 70’s: a cult classic using rigorous visual composition to penetrate the innermost recesses of the soul.”

-Berenice Reynaud, The Chicago Reader

Montclair Film Festival Premiering Restored ‘The Diary of Anne Frank’

Dave McNary

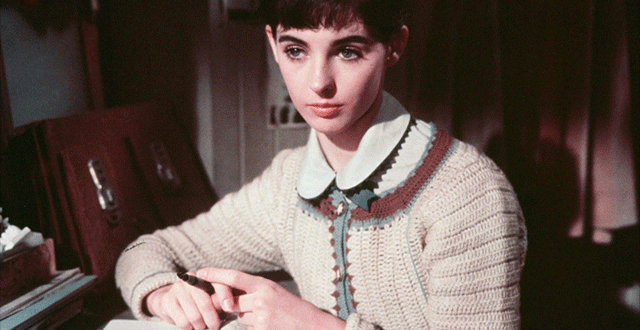

The Montclair Film Festival will hold the world premiere of the restoration of the 1959 movie “The Diary of Anne Frank,” Variety has learned exclusively.

The black-and-white film, directed by George Stevens, has been restored by Twentieth Century Fox and the Film Foundation. The holocaust drama was nominated for eight Academy Awards and won three, including best supporting actress for Shelly Winters. It will be screened May 5 at the Clairidge 2.

The festival, now in its eighth year, will take place May 3-12 in Montclair, N.J., and features more than 150 films, events, discussions and parties. The festival had previously announced that it would open with a screening of Tom Harper’s “Wild Rose,” with star Jessie Buckley attending for a post-screening Q&A at the Wellmont Theater.

This year’s Storyteller Series will include A Conversation with Mindy Kaling, moderated by Stephen Colbert, taking place May 4 at the Wellmont and A Conversation with Ben Stiller, moderated by Colbert, on May 5 at MKA Upper School. Olympia Dukakis will attend for a Q&A following the May 5 screening of Harry Mavromichalis’ documentary “Olympia” at MKA Upper School.

Documentary highlights include Roger Ross Williams “The Apollo,” which will screen May 4; Don Argott and Sheena M. Joyce’s “Framing John Delorean,” portions of which were shot in Montclair; Montclair’s own Erin Lee Carr with true crime thriller “I Love You, Now Die: The Commonwealth Vs. Michelle Carter”; and the premiere of Ken Spooner and Mike Mee’s “Life With Layla,” which examines the opioid epidemic through the experiences of a New Jersey family.

The festival is also screening its first Family Centerpiece film, Mark Deeble and Victoria Stone’s “The Elephant Queen,” presented by The Nature Conservancy. The Documentary Centerpiece will be “Miles Davis: Birth of the Cool” on May 10, with director Stanley Nelson attending for a Q&A.

“This year’s festival program reflects a wide range of concerns and points of view that speak to the

current state of our cinematic world,” said Montclair Film Executive Director Tom Hall. “Film is a global community, held together by our collective passion for the power of cinema. We look forward to our artists and audiences coming together to share that passion at the festival.”

Here are the titles in competition:

DOCUMENTARY FEATURE COMPETITION

AMERICAN FACTORY, directed by Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert

HONEYLAND, directed by Tamara Kovetska and Ljubomir Stefanov

THE HOTTEST AUGUST, directed by Brett Story

MIDNIGHT FAMILY, directed by Luke Lorentzen

PAHOKEE, directed by Ivete Lucas and Patrick Bresnan

FICTION FEATURE COMPETITION

DIVINE LOVE, directed by Gabriel Mascarano

A FAMILY SUBMERGED, directed by Maria Alche

MANTA RAY, directed by Phuttiphong Aroonpheng

MONOS, directed by Alejandro Landes

ONE MAN DIES A MILLION TIMES, directed by Jessica Oreck

FUTURE/NOW COMPETITION

JULES OF LIGHT AND DARK, directed by Daniel Laabs

LIGHT FROM LIGHT, directed by Paul Harrill

MICKEY AND THE BEAR, directed by Annabelle Attanasio

PREMATURE, directed by Rashaad Ernesto Green

THE WORLD IS FULL OF SECRETS, directed by Graham Swon

NEW JERSEY FILMS COMPETITION

FOR THEY KNOW NOT WHAT THEY DO, directed by Daniel Karslake

THE INFILTRATORS, directed by Cristina Ibarra and Alex Rivera

LIFE WITH LAYLA, directed by Ken Spooner and Mike Mee

MOSSVILLE: WHEN THE GREAT TREES FALL, directed by Alexander Glustrom

WHAT SHE SAID: THE ART OF PAULINE KAEL, directed by Rob Garver