News

Seven Films to be Preserved Through Avant-Garde Masters Grants

A portrait of a drag artist by Heather McAdams, a structural film by Lawrence Gottheim, two evocations of city/ landscapes by Paul Downs, and three works by Carolee Schneemann will be preserved and made available through the 2022 Avant-Garde Masters Grants, awarded by The Film Foundation and the National Film Preservation Foundation.

Chicago-based alternative cartoonist Heather McAdams assembled her films from found footage, viewing pop culture’s scraps through an anarchic feminist lens. While teaching in Lexington, Kentucky, McAdams befriended Bradley Harrison Picklesimer, owner of a drag bar/nightclub on Main Street. Assembled “like a crazy quilt,” to quote McAdams, Meet…Bradley Harrison Picklesimer (1988) scrambles found and direct footage to cover its subject’s personal ups and downs, along with his thoughts on gender-bending. The film, praised as a “hilarious collaboration with its eponymous star” by Manohla Dargis in the Village Voice, will be preserved by the Chicago Film Society.

Lawrence Gottheim’s Your Television Traveler (1991) will be preserved by Binghamton University, whose cinema department Gottheim founded and chaired. Its first part presents the image of a NASA rocket falling away from a spacecraft to reveal the earth. On the soundtrack are fragments from an interview Gottheim conducted with a Cuban woman in Havana. The film’s second part repeats the first but with superimpositions of a religious ceremony in Havana and sound from a record on early space travel, which features astronauts identifying with the stereotyped comedic character José Jiménez. Part three superimposes on the previous section the sounds and images from a “Television Traveler” TV show about St. Petersburg, Florida.

Electronic Arts Intermix, working with the Carolee Schneemann Foundation and Anthology Film Archives, will preserve three films by groundbreaking performance and multidisciplinary artist Carolee Schneeman. Viet-Flakes (1965) compiles a wide-ranging set of images of Vietnam War atrocities from foreign magazines and newspapers; within them Schneemann “travels” by using drugstore magnifying glasses. Red News (1966) was described by Schneemann as a found footage “compendium of disasters…one explosion after another,” including car crashes and war footage. Plumb Line (1968–71), the second part of what scholar Scott MacDonald called Schneemann’s “autobiographical trilogy,” is a portrait of the end of a romantic relationship, assembled from scrap diary footage, with a soundtrack of pop music, birds and cats, and a monologue by Schneemann lamenting the Vietnam War and lost love. She tinted, scratched, and collaged 8mm celluloid before using a step printer to reprint the frames onto 16mm.

The Walker Art Center will preserve two works by Minneapolis-based Allen Downs (d.1983). A professor of photography and film at the University of Minnesota from 1950 through 1977, he started the University’s film program in 1952 and its study-in-Mexico art program in 1972. His films emphasized rhythm, color, and movement; no less a figure than Bruce Baillie credited Downs with teaching him everything he knew about filmmaking. In The Color of the Day (1955), Downs journeys through St. Paul and the West Bank of Minneapolis, capturing urban landscapes through the moments of a summer’s day. Influenced by the street photographers of the era, the film makes use of window reflections and the bright colors of advertisements. Love Shots (1971), the only film by Downs screened nationwide, uses optical printing, time lapse photography, rapid editing, and direct animation to capture the colors and feel of the mountains of Mexico and springtime in Minnesota.

Over the course of 20 years the Avant-Garde Masters Grant program, created by The Film Foundation and the NFPF, has saved 214 films significant to the development of the avant-garde in America. Funding is provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. The grants have preserved works by 83 artists, including Kenneth Anger, Shirley Clarke, Bruce Conner, Joseph Cornell, Oskar Fischinger, Hollis Frampton, Barbara Hammer, Marjorie Keller, George and Mike Kuchar, and Stan VanDerBeek.

Olivia Harrison is Awarded the UNAM Film Library Medal at the 20th FICM

Gustavo R. Gallardo

At the 20th Morelia International Film Festival (FICM), the producer, writer, curator and philanthropist, Olivia Harrison, received the UNAM Film Library Medal for her support in restoring, among others, El (1953), by Luis Buñuel, thereby contributing to keeping Mexico’s filmographic memory alive.

Attended by the president, vice-president and director of the festival, Alejandro Ramírez, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Batel, and Daniela Michel, as well as the executive director of The Film Foundation, Margaret Bodde, the director of Distribution of the UNAM Film Library, Jorge Martínez Micher, and Hugo Villa Smythe, who was there on behalf of the director of the Film Library.

"Personally, it's my favorite movie in the history of cinema, so sharing with all of you is a very magical moment for me," said Daniela Michel.

"We also want to give a very special thanks to Guillermo del Toro, who was unable to join us, but has been instrumental in restoring this film," he added.

The Material World Foundation, headed by Olivia Harrison, has collaborated with The Film Foundation, an organization created by Martin Scorsese, in the restoration of invaluable classic Mexican films such as Enamorada (1946), by Emilio Fernández; Dos monjes (1934), by Juan Bustillo Oro; and Redes (1936), by Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel, which have been presented at past editions of FICM.

For this reason, Martínez Micher said, reading from the document delivered by the UNAM Film Library, that the UNAM Film Library Medal was awarded to Olivia Harrison for her contribution "to enriching the world's film heritage and keeping it alive in our collective memory," and added: "Olivia, my dear, with this medal you take a little piece of Mexican cinema with you."

Olivia Harrison thanked FICM and the UNAM Film Library for the award, and said that Mexican cinema "brings back great memories of my family."

“My family loved the classic movies so much that they were always playing in the background. We always had a Mexican movie or soap opera on TV. For us, this was very important,” she said, also sharing that George Harrison loved the cinema and that she encouraged him to watch Mexican films “even without subtitles”.

In Él, Francisco Galván de Montemayor is a wealthy man with a serene appearance; a religious conservative and a virgin. He meets Gloria at the Holy Thursday foot-washing ceremony. Later on, at a party in his mansion, he woos her and then marries her. But from the wedding night on, his jealousy transforms him into an obsessive and paranoid being who sees murder and mutilation as a solution to his madness

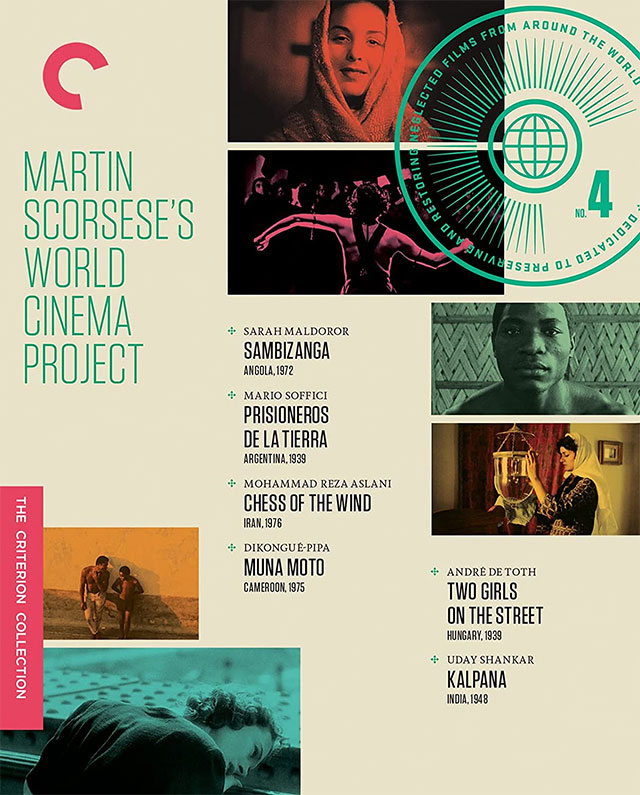

DIFFERENT COUNTRIES, SAME TROUBLED PLANET: MARTIN SCORSESE’S WORLD CINEMA PROJECT, NO. 4

Michael Barrett

Criterion’s fourth box set of Martin Scorsese‘s World Cinema Project is part of the ongoing initiative of The Film Foundation to finance and coordinate restorations of important films from countries with little or no self-funded resources. Packaged as a DVD/Blu-ray combo, the box set contains six features and a booklet. Although these films come from different countries, decades, and languages, they reveal similarities in social conscience and film experiment.

Four of the six features in this box sex present explicit critiques of their government’s policies and forces of oppression, which is probably a great way to become obscure and overlooked. The other two, Chess of the Wind and Two Girls on the Street, are also at least highly critical of social conventions, male supremacy, and industrialization. These films might hail from different countries, but they were all made on the same troubled planet.

Prisonieros de la Tierra (1939) Director: Mario Soffici

The opening credits in Prisonieros de la Tierra declare that all is peaceful and harmonious today in the northern Argentine region where the story takes place, but that the events date from an earlier pioneer era of blood and alcohol. Then the first scene announces its date as 1915, which isn’t that long ago for a film of 1939. Here the filmmakers try to pacify cultural critics (or so we guess) by implying that we can speak of such exploitations and depravities because they belong to a distant past before today’s enlightened era. This is a common strategy when films point out unpleasant legacies that might upset those who benefited from them.

Prisonieros de la Tierra‘s quickly introduces its characters, most of whom are referred to as “Mensú” and who sometimes speak Guarani, indicating indigenous status. Spanish Wikipedia informs us that Mensú is a Guarani word derived from the Spanish word for “monthly” and refers to workers recruited to work on yerba mate plantations. As Sofici’s film depicts, the workers were often recruited forcibly and kept in permanent debt to “the company store”, frequently while dying of malaria and other diseases. Their conditions were akin to slavery and worse than sharecropping since they had no share in the crop.

Several Latin American writers called attention to this exploitation. Among these was Horacio Quiroga, whose stories inspired Soffici’s Prisonieros de la Tierra (or Prisoners of the Land or Prisoners of the Earth) a couple of years after Quiroga’s death in 1937. One of the screenwriters is Dario Quiroga, the author’s son. His co-writer is poet and playwright Ulyses Petit de Murat, who here launches his career as Argentina’s most prolific screenwriter.

Melodramas about serious issues commonly dramatize them through emblematic characters in confused romantic relationships, so Prisonieros de la Tierra presents its hero, Esteban Podeley (Ángel Magaña), as an enlightened peón who reads books about his exploitation. Such education is disapproved as dangerous by foreign gringo boss Köhner (Francisco Petrone), who has an unscrupulous job whipping all those workers into line for the plantation. Among the film’s strong points is that Köhner remains an understandable human while being the villain.

The third point in their triangle is the lovely Andrea (Elisa Galvé). She’s the daughter of the self-hating doctor (Raúl De Lange), who has passed from youthful idealism to alcoholic nihilism. She considers herself spiritually with the workers because her mother was half-native. She commits herself to the love of Podeley while the lonely Köhner fumes with jealousy and hates his life.

In this way, personal issues lead to political rebellion in a climax – an angry call to revolution mixed with star-crossed tragedy. The most striking scene is possibly inspired by Eliza’s whipping of Simon Legree in the ubiquitous stage productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. However, this scene goes beyond our initial animal pleasure at the payback. More than one scene and character in Prisonieros de la Tierra harness Christlike imagery. Also notable is the symbolism of falling trees in the Amazon jungle.

One amazing moment of blurred, drunken subjectivity involves hallucination and horror that reminds us of Quiroga’s reputed affinity with Edgar Allan Poe. These tales are adapted from Quiroga’s story collection called Stories of Love, Madness, and Death (Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte, 1917). That tells you plenty.

Prisonieros de la Tierra is probably the first Argentine film to address such a subject. During the ’50s, the industry made at least two melodramas about the Mensú based on literary sources written years after Quiroga died. Hugo del Carril’s Las Aguas Bajan Turbias (1952) is based on Afredo Varela’s Dark River (El río oscuro, 1943). Armando Bó’s El trueno entre las hojas (1958) is based on the same-titled 1953 book by Augusto Roa Bastos. There’s a trilogy waiting to be gathered.

As a child, Soffici emigrated from Italy to Argentina and eventually became a fixture in the national cinema, directing more than 40 films from the ’30s to the ’60s. In his Dictionary of Film Makers (1972, University of California Press), the French historian Georges Sadoul pronounces Soffici the best Argentinian filmmaker of the 1935-45 period for “portraying Argentinian realities with an authenticity and a particular social sense unusual in his country.”

In Prisonieros de la Tierra, we see that authenticity in the frequent use of outdoor locations and in the excellent high-contrast black and white photography of Pablo Tabernero, which goes in a heartbeat from documentary-like to grim to lyrical. This may have been the first film shot in the Amazonian region where the story takes place, very remote from Buenos Aires. The actor who originated the project died of appendicitis there, far from medical attention, and had to be replaced.

The restoration shows why Jorge Luis Borges hailed the film as a landmark and why it was popular with audiences and critics. In a bonus discussion about the film’s history, we learn that only one wretched and battered 16mm print of Prisonieros de la Tierra existed in its own country. The restorers were able to locate 35mm prints in Paris and Prague.

Sambizanga (1972) Director: Sarah Maldoror

Sambizanga, named for a community outside Angola’s capital of Luanda, bears a few similarities to Prisioneros de la Tierra. While both have documentary elements, Sambizanga goes farther in that direction and feels especially indebted to Neorealism. Both films are about colonization and resistance, showing characters who speak the dominant European language and their language.

In Sambizanga, the setting is the Portuguese colony of Angola in Africa, and the events take place in early 1961, just before the long war that was still going on during filming. The film had to be shot next door in the Congo with Angolan non-professionals involved in the revolutionary movement.

Sambizanga‘s adapts a novella by a Portuguese anti-colonial author, José Luandino Vieira, called A vida verdadeira de Domingos Xavier (The Real Life of Domingos Xavier). That title implies that Xavier dominates the narrative, but the strategy of filmmaker Sarah Maldoror is to emphasize everyone around Xavier (Domingos de Oliveira), especially the struggles of his wife Maria (Elisa Andrade).

Sambizanga opens with the type of everyday documentation that will fill the narrative. Xavier is working at his construction job. After a curious encounter with his white boss, who asks him to stop by that evening, Xavier tells a colleague in confidence that this man is a friend. As we will put together later, the boss is distributing revolutionary leaflets. Xavier is arrested and taken to prison in Luanda for his part in those leaflets, and he refuses to name his associates.

From the beginning, whole communities of Africans observe his fate, passing information by word of mouth and offering consolation to Maria, who makes long journeys with her baby trying to see Xavier. Occasionally we see him in prison, but the doings of Maria and others dominate Sambizanga in accordance with Maldoror’s belief that revolution cannot happen without women and children and communal cooperation is at least as vital as individual actions. This makes the film a collection of often lyrical, almost digressive scenes that linger on intense close-ups or wide shots of the community and landscapes.

At one point, a revolutionary leader is educating men in a sewing factory. He declares with a classic Marxist bluntness that “There are no white people, there are no mulattoes, there are no black people. There are only the rich and the poor, and the rich are enemies of the poor.” Sambizanga promotes the activities of the Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), whose first president was Maldoror’s husband Mário de Andrade. He co-wrote the film with French poet Maurice Pons.

Maldoror was the daughter of a Frenchwoman and a father from Guadeloupe, and she dedicated her life to pan-African topics. She adopted her surname from the unconventional anti-hero of Comte de Lautréamont’s novel The Songs of Maldoror (Les Chants de Maldoror, 1869), so beloved by the Surrealists. Sambizanga was her only completed feature, though she’d made a short based on a similar story by Luandino Vieira. It would have been nice to see that short here.

Maldoror spent the rest of her career making many documentaries for French television. She died in 2020. A bonus segment interviews her and her daughter Annouchka de Andrade. They explain that some “miserabilist” critics found fault with Sambizanga for its physically beautiful characters and rich color photography. Maldoror rejected the idea that poor people aren’t entitled to beauty.

Muna Moto (1975) Director: Dikongué-Pipa

Shot in Cameroon in black and white, Muna Moto (or A Child of Another) is perhaps the most avant-garde film in this set. As befits films with a complex structure, the story is very simple. As in Prisioneros de la Tierra, the hero’s marriage ambitions are thwarted by a personal triangle and social conditions, and once again, a falling tree becomes a metaphor.

Ngando (David Endene) and Ndome (Arlette Din Bell) wish to marry but first come many hoops. Ngando must pay an exorbitant bride price he can’t afford. His family is dominated by his uncle Mbongo (Abia Moukoko), who, upon the death of Ngando’s father, has inherited and married Ngando’s mother, just like Hamlet’s Claudius, and also her daughters.

This familial polygamy is sanctified by tradition, and the boorish uncle blames his wives for the fact that he has no children. The obvious conclusion, which nobody spells out, is that Mbongo is the sterile one. He thinks he can solve his problem by marrying Ndome.

Muna Moto‘s story will interrogate this tradition harshly by personalizing it through the tyrannical Mbongo, who can be seen as symbolizing all oppressive patriarchal traditions and the general powers that be. A few passages link Ngando’s problems to the economic policies of the newly independent post-colonial government, though Dikongué-Pipa was obliged to tread lightly on political criticism.

Muna Moto‘s basic story is presented in fragments of memory after Ngando has created a stir at a family celebration. Scenes will float around this confrontation. There are moments of fantasy, such as when the uncle imagines Ndome’s future pregnancy and even a theatrical dream sequence in which Ngando hears his father. Dikongué-Pipa uses editing and sound mixing imaginatively to string ideas together and explain events. The ending uses a beautiful melancholy song by Georges Anderson.

In a bonus interview, Dikongué-Pipa declares that his spiritual mentors are Luis Buñuel, Ingmar Bergman, and the Italian Neorealists.

Chess of the Wind (Shatranj-e Baad, 1976) Director: Mohammad Reza Aslani

As in Muna Moto, a hated patriarchal tyrant dominates the proceedings, at least for Chess of the Wind’s first half. Haji Amou (Mohamad Ali Keshavarz) throws his weight around the fancy Iranian mansion of an earlier era, being especially cruel to the wheelchair-bound Lady Aghdas (Fakhri Khorvash), who’s introduced smashing bottles with a little swinging flail.

After behaving like one of those obnoxious figures in an episode of Perry Mason or Murder She Wrote who anger everyone until the inevitable murder, the patriarch gets dispatched. Sheyda Gharachedaghi scores this scene and others in a hooting modernist dissonance with traditional instruments. For the record, the composer is a woman, as is production designer Houri Etesam, and these aren’t traditional choices in Iran’s cinema or anybody’s.

Despite the murder, Chess of the Wind is no whodunit because we see clearly who engages in the conspiracy to knock him off and hide the body. Then the plot goes in a direction strongly reminiscent of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Diabolique (1955).

At various points, for punctuation, the action shifts to a wide shot of women washing clothes at a fountain while commenting and gossiping about the action. These scenes are presented without cuts but with the camera sometimes gliding in slowly. This “Greek chorus” or “vox populi” element indicates that the working classes are always paying attention and judging the activities of their “betters”. Since this chorus is all female, it carries a whiff of Susan Glaspell’s story “A Jury of Her Peers” (1917), which might have been known to Aslani through its incarnation as a 1961 episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Let’s ask him.

A crucial role belongs to Shohreh Aghdashlou, making her film debut as the servant girl or handmaiden Kanizak. She serves her Lady Aghdas even to the point of a startling implication of lesbian passion, presented distantly but noisily. We can imagine this scene raising Persian eyebrows in 1976. Since being Oscar-nominated for House of Sand and Fog (Vadim Perelman, 2003), Aghdashlou has a thriving Hollywood career that includes the X-Men and Star Trek franchises and the sci-fi television series The Expanse. Today she sounds like Leonard Cohen, and that’s not a knock.

Houshang Barlou’s photography frequently curves with catlike prowl around the characters in this claustrophobic setting. In one hair-raising sequence, it even tracks someone down the stairs. These sequences cast an orange-yellow light, perhaps to increase a sense of fevered delirium. In the making-of, Arslani makes visual references to Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) and innovative Iranian painter Kamal-ol-Molk.

Chess of the Wind premiered badly at a Tehran festival in 1976 and soon joined the legacy of pre-Islamic Revolution cinema being banned in 1979. Recently rediscovered by an accident that can fairly be called miraculous, it’s been revelatory at festivals.

Two Girls on the Street (Két lány az utcán, 1939) Director: André de Toth

Director André de Toth is known as a Hollywood guy, the only director in this whole set who worked there. Among the many cinematic emigres who landed in Hollywood during WWII, he built a reputation as a reliable craftsman in B films, mostly thrillers and westerns. Dark Waters (1944), Ramrod (1947), and Pitfall (1948) are worthy examples. Despite being blind in one eye, he directed the 3-D horror House of Wax (1953).

The third of his five Hungarian films, Two Girls on the Street follows the perspective of two women of different classes who become roommates in the big city. The slightly older and wiser Gyöngyi (Mária Tasnádi Fekete) – who begins the story by being tossed out of her comfortable home with an unwed pregnancy and loses the baby in childbirth – takes pity upon the naïve and somewhat tiresome Vica (Bella Bordy).

While these characters bewail the fate of women and laborers and bemoan men in general and rich men in particular, de Toth’s script is savvy enough to present its women as flawed, multi-faceted humans. Vica comes across as a clumsy schemer who tries to manipulate people without showing finesse, which often ends badly. However, one of her ploys succeeds in landing the women in a snazzy apartment under the patronage of Gyöngyi’s father.

Gyöngyi also gets manipulative under the guise of being protective, as though Vica is her lost daughter or little sister. Gyöngyi shows jealousy of Vica and resents her attention from a rich architect (Andor Ajtay), and this behavior may imply a submerged erotic attraction between the women. In case you think that’s a stretch for any 1939 film, their all-girl nightclub band shows that one of its members is an effeminate man in drag who mingles freely in the dressing room.

After some narrowly averted melodrama, both women move on to new phases. The final scene shows Vica, now literally on top of everyone else in a new highrise, oblivious to the struggling female laborers who have replaced her in the working-class chain. It’s a cynical little note to strike in the middle of a happy ending. The film’s booklet points out that this cynicism matches the recurring theme song, which is about “saving your breath” because everybody lies.

Shot in the streets of Budapest full of urban bustle and modern construction, Two Girls on the Street mixes realism with a few moments of subjective expressionism. The story is brisk and beady-eyed, with commentary and observation from various side characters. As we’ve hinted, some language and sexual elements are franker than concurrent Hollywood films.

Kalpana (1948) Director: Uday Shankar

Among India’s most important 20th Century artists is dancer and choreographer Uday Shankar, a pioneer in mixing modern with traditional elements into a hybrid of his invention. The highly personal Kalpana is his only film. We said earlier that Muna Moto may be the most avant-garde film in Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 4, but Kalpana runs neck and neck with it.

Kalpana opens with a movie pitch between Shankar and a money-minded mogul whose motto is “Box office!” Shankar pitches the script as dramatized before our eyes. It’s his tale of founding a modern dance troupe and school in the Himalayas (as he did in real life), as tricked up with Hindi melodrama about the artist’s struggle between a Good Girl (symbolizing art) and a temptress (symbolizing the commercial world). Shankar’s wife, Amala Uday Shankar, plays the good Uma, and Lakshmi Kanta plays Kamini, the jealous vamp.

There’s much strife and digression, but that’s not the point. The point is that much of this is conveyed via modern dance numbers that take full advantage of cinematic language by doing things you can’t show on a stage. Visual devices include the editing and superimposition of multiple images on different planes of perspective. Some pieces are presented more theatrically, yet with sweeping camera moves and much elaborate design and lighting.

By coincidence, another film from this year used similar devices: Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger’s The Red Shoes. Kalpana is shot in black and white by K. Ramnoth rather than glorious color, but much of it looks as striking as a Busby Berkeley film on a smaller budget. Workers are instructed to become machines in one number that evokes Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927).

The emphasis on dance and symbolism makes the storyline almost an abstract concept, although there are many moments of social criticism via direct lectures. Mr. Gandhi and Mr. Nehru are mentioned by name as Shankar implores that India move forward into the modern world by forsaking caste and regional division, the oppression of women, and the lure of the commercial. Early scenes convey an abusive childhood full of beatings, while gaps in this section’s narrative strongly imply that footage may be missing.

One detail that modern viewers will notice is that we first meet the hero as a boy being punished for dressing as a girl to dance on a homemade stage. Cross-dressing isn’t singled out for blame, only the desire to dance. In a later dance, female and male figures superimpose on each other to imply an internal sexual collaboration.

In the bonus discussion, scholars trace Kalpana‘s influence on the Bollywood cinema of Guru Dutt (a student of Shankar), Raj Kapoor and V. Shantaram, and the fact that Satyajit Ray watched it many times. Some of the participants went on to big film careers. For the record, Shankar’s younger brother is an equally major figure in music, Ravi Shankar.

Each film in Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 4 comes with a brief intro by Scorsese and a bonus segment of appreciation. My only complaint about this fine and noble series is that new volumes emerge too slowly. We must remember to be grateful that they emerge at all. Each box is an illuminating treasure of film history far from Hollywood, so this is possibly the single most important ongoing series in home video.

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project Returns with Fourth Criterion Box Set

Brian Tallerico

Usually, this feature would offer mini-reviews of the six films in the latest “World Cinema Project,” an essential release from the Criterion Collection. However, life got hectic enough (including three Covid diagnoses in my house) that I haven’t been able to sample the set like I wanted to but didn’t want to let its release go by. Therefore, consider this post more informative than critical, a detailed look at what’s in the latest box set instead of an opinion of their quality.

I have a feeling that quality isn’t really a concern here, but mostly wanted to make sure people knew that there’s a fourth box set from Martin Scorsese’s The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, a group that restores and preserves films that could have otherwise been lost to history. In this case, they have highlighted films from multiple eras (as old as 1939 and as new as 1976) and countries, including Cameroon, Argentina, Iran, and Angola. Criterion has been accused of being too Euro-centric in the past, and these “World Cinema Project” sets go a long way to correcting that impression. Each film has been delicately remastered, and the entire box set is accompanied by a fantastic booklet of essays about the six works assembled. Below, you will find descriptions of all six films, courtesy of Criterion, along with a list of the special features. Buy it here. You won’t regret it. (Also don’t miss Godfrey Cheshire’s four-star review of one of the titles, “Chess of the Wind,” linked here.)

“Sambizanga” (1972)

A bombshell by the first woman to direct a film in Africa, Sarah Maldoror's chronicle of the awakening of Angola's independence movement is a stirring hymn to those who risk everything in the fight for freedom. Based on a true story, "Sambizanga" follows a young woman (Elisa Andrade) as she makes her way from the outskirts of Luanda toward the city's center looking for her husband (Domingos Oliveira) after his arrest by the Portuguese authorities—an incident that ultimately helps to ignite an uprising. Scored by the language of revolution and the spiritual songs of the colonized Angolan people, and featuring a cast of nonprofessional actors—many of whom were themselves involved in anticolonial resistance—this landmark work of political cinema honors the essential roles of women, as well as the hardships they endure, in the global struggle for liberation.

“Prisioneros de la Tierra” (1939)

The most acclaimed film by one of classic Argentine cinema's foremost directors, Mario Soffici's gut-punching work of social realism, shot on location in the dense, sweltering jungle of the Misiones region, simmers with rage against the oppression of workers. A group of desperate men are conscripted into indentured labor on a treacherous, disease-ridden yerba maté plantation under the control of the brutal foreman Köhner (Francisco Petrone)—a situation that boils over in an explosive act of rebellion led by the defiant Podeley (Ángel Magaña), and made all the more tense by the fact that Köhner and Podeley love the same woman: Andrea (Elisa Galvé), the sweet-spirited daughter of the camp's doctor. The expressionistic, shadow-sculpted cinematography of Pablo Tabernero evokes the feverish dread of a place where suffocating heat, economic exploitation, and unremitting cruelty lead inexorably to madness and violence.

“Chess of the Wind” (1976)

Lost for decades after screening at the 1976 Tehran International Film Festival, this rediscovered jewel of Iranian cinema reemerges to take its place as one of the most singular and astonishing works of the country's prerevolutionary New Wave. A hypnotically stylized murder mystery awash in shivery period atmosphere, Chess of the Wind unfolds inside an ornate, candlelit mansion where a web of greed, violence, and betrayal ensnares the potential heirs to a family fortune as they vie for control of their recently deceased matriarch's estate. Melding the influences of European modernism, gothic horror, and classical Persian art, director Mohammad Reza Aslani crafts an exquisitely restrained mood piece that erupts into a subversive final act in which class conventions, gender roles, and even time itself are upended with shocking ferocity.

“Muna Moto” (1975)

Director Dikongué-Pipa forged a new African cinematic language with "Muna Moto," a delicate love story with profound emotional resonance. In a close-knit village in Cameroon, the rigid customs governing courtship and marriage mean that a deeply in love betrothed couple (David Endéné and Arlette Din Belle) can be torn apart by the lack of a dowry and by another man's claiming of the young woman as his own wife—a rupture that sets the stage for a clash between a patriarchal society and a modern generation's determination to chart its own course. Luminous black-and-white cinematography and stylistic flourishes yield images of haunting power in this potent depiction, told via flashback, of the challenges of postcolonialism and the devastating consequences of a community's refusal to deviate from tradition.

“Two Girls on the Street” (1939)

The maverick Hollywood stylist André de Toth sharpened his craft in his native Hungary, where he directed five films, including this chic, dynamically paced melodrama studded with deco decor and jazzy musical interludes. Mária Tasnádi Fekete and Bella Bordy sparkle as upwardly mobile working women—one a musician in an all-girl band, the other a bricklayer—who join forces as they both try to make it in Budapest, supporting each other through changing economic fortunes, the advances of lecherous men, and the highs and heartbreaks of love. Kinetic camera work, brisk editing, and avant-garde imagery abound in "Two Girls on the Street," an often strikingly modern ode to the power of working-class female solidarity.

“Kalpana” (1948)

A riot of ecstatic imagery, performance, and set design, the only film by the visionary dancer and choreographer Uday Shankar is a revolutionary celebration of Indian dance in its myriad varieties and a utopian vision of cultural renewal. Unfolding as an epic film within a film, "Kalpana" tells the story of an ambitious dancer (Shankar) determined to open a cultural center devoted to breathing new life into India's traditional artistic forms; meanwhile, the obvious adoration between him and his lead dancer (Shankar's wife and collaborator, Amala Uday Shankar) arouses the jealousy of his enterprising companion (Lakshmi Kanta). Swirling surrealist dance spectacles—featuring dance masters and young performers, many of whom would become stars in their own right—are interwoven with anticolonial, anticapitalist commentary for a radical, proto-Bollywood milestone that is one of the most influential works in Indian cinema.

New introductions to the films by World Cinema Project founder Martin Scorsese

New and archival interviews featuring Indian film historian Suresh Chabria and filmmaker Kumar Shahani (on "Kalpana"); Argentine film historians Paula Félix-Didier and Andrés Levinson (on "Prisioneros de la tierra"); "Two Girls on the Street" director André de Toth; and "Sambizanga" director Sarah Maldoror and Annouchka de Andrade, Maldoror’s daughter

New program by filmmaker Mohamed Challouf featuring interviews with "Muna moto" director Dikongué-Pipa and African film historian Férid Boughedir

"The Majnoun and the Wind" (2022), a documentary by Gita Aslani Shahrestani, daughter of "Chess of the Wind" director Mohammad Reza Aslani, featuring Aslani, members of the film’s cast and crew, and others

PLUS: A foreword and essays on the films by critics and scholars Yasmina Price, Matthew Karush, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Aboubakar Sanogo, Chris Fujiwara, and Shai Heredia