News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

Live long enough and you’ll see so many truisms accreting from the ether of that they will come to seem like a wall of barnacles at the bottom of a boat in harbor. In the world of cinema, for instance. We have “slow = boring” (tell that to fans of the Godfather films, There Will Be Blood or Once Upon a Time in Hollywood). We have “people don’t like reading subtitles.” We have “people don’t like black and white.” Of more recent vintage, there’s “old movies are racist and sexist.”

And then there’s this one: “people don’t like to watch silent movies.”

A friend of mine told me that when he started showing silent movies to his daughter, her first reaction was: “What are they saying?” And then she got used to it. Which is unsurprising. But even when she was wondering what the people onscreen were saying, she was still interested.

My sons were entranced with silent films when they were boys. I remember my younger son asking me if we could see Metropolis again… the complete version! Their sister, almost two, is engrossed by Chaplin films. The only difference between my friend’s daughter and my children and anybody else is that we love the work, which means we know the work, and we want to introduce them to it.

Whenever anyone spouts any of the above truisms, always mindlessly (because they can’t really be spouted any other way), it’s because they haven’t had anyone in their life to introduce them to anything slow, subtitled, black and white, older than 2 years, or silent… or some combination thereof.

The Film Foundation has participated in or facilitated the restoration of somewhere in the neighborhood of 250 silent films. The fact that any of them has survived is a miracle. They are the source. They are vivid records of a world—many worlds—gone by. Many of them are astonishingly beautiful and spontaneously inventive, unencumbered by many of the conventions that solidified over the years. And when you really look at them, with your full attention, and maybe allow yourself to acclimate to them, you will enter a world of wonders.

- Kent Jones

2021 CANNES CLASSICS SELECTION

As every year, the Festival de Cannes presents a selection of the best restored prints and invites us to explore again the history of Cinema.

The curtain rises with Mark Cousins' pre-opening documentary; the rediscovery of director-actor Kinuyo Tanaka and Spanish director actress, screenwriter and producer Ana Mariscal; a tribute to director and actor Bill Duke; a close-up on the first African-American director Oscar Micheaux; the 1959 Palme d'Or; the 70th anniversary of Les Cahiers du cinéma; the modesty of Jacques Doillon; two wonders from Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger; Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation and the World Cinema Project; Tilda Swinton's first role; cinema from the Ivory Coast, former Yugoslavia, Italy and former Czechoslovakia; Alain Resnais's film at Cannes in 1966; Irène Jacob by Krzysztof Kieślowski and Jeanne Moreau by Philippe de Broca; some French thriller; “soviet” films welcomed in competition at Cannes; Orson Welles’s magic, the style of Max Ophüls; four outstanding documentaries on the great producer Jeremy Thomas, Satoshi Kon, Luis Buñuel and Yves Montand; a docudrama full of cinephile fury; and twenty years later, the unsolved mystery of Mulholland Drive...

Here is Cannes Classics 2021!

A Tribute to Bill Duke

The director, actor (for John McTiernan, Samuel Fuller, John Landis or Steven Soderbergh) and producer, in Competition at Cannes with A Rage in Harlem in 1991, returns to the Croisette with his first film as director, presented at the Semaine de la critique in 1985.

The Killing Floor by Bill Duke

(1985, 1h58, United States)

Presented by Made in U.S.A. Productions, Inc. The UCLA Film & Television Archive facilitated in-house 4K scanning of the film’s 16mm original picture negative, which is vaulted in the Archive’s Sundance Institute Collection. Under the supervision of film's executive producer/co-writer, Elsa Rassbach, Made in U.S.A. Productions completed the 4K restoration with color grading by Alpha-Omega digital in Munich and Planemo post-production in Berlin. In addition, the soundtrack was digitally restored by Deluxe Entertainment Services Group from the film’s original 35 mm audio mono mix mag track. The film was restored in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the 1919 Chicago Race Riot.

Director Bill Duke and executive producer and co-screenwriter Elsa Rassbach in attendance.

Kinuyo Tanaka, actress and filmmaker

Kinuyo Tanaka, one of the greatest Japanese actresses, made her first film in 1953, entering the Cannes Competition in 1954. She returned in 1961 and 1964 as a performer. She was the only active filmmaker of the golden age of Japanese cinema and her second feature film, presented here, is a reflection of her immense talent. This new version restored in 4k by Nikkatsu inaugurates the Tanaka event, a forthcoming retrospective of her 6 films.

Tsuki wa noborinu (La Lune s’est levée / The Moon Has Risen) by Kinuyo Tanaka

(1955, 1h42, Japan)

Presented by Nikkatsu and distributed in France by Carlotta Films.

Restored from the original 35mm positive preserved by Nikkatsu Corporation. 4K restoration by Nikkatsu Corporation and The Japan Foundation at Imagica Entertainment Media Services, Inc laboratory.

Ana Mariscal, Spain in the feminine form

Pioneer director of Iberian cinema, Spanish actress, screenwriter and producer Ana Mariscal directed ten rich films, as non-conformist as they are visually splendid. As a foretaste of her work, here is a nostalgic chronicle of a modest Spanish village in the 1960s.

El camino (Le Chemin / The Path) by Ana Mariscal

(1964, 1h31, Spain)

Presented by David García Rodríguez. 4K digitalization and restoration supervised by Ramón Lorenzo Sierra from the original edited negative and vintage dupe. Sound restoration from the original sound negative. Laboratory: Vivavision (Madrid). Theatrical distribution in France: Karmafilms Distribution. Release in France: October 2021. On video in France: UHD collector edition, November 2021.

Oscar Micheaux

The first African-American director in the history of American cinema is honored in a sublime restored copy of one of his greatest films accompanied by a fascinating documentary.

Murder in Harlem by Oscar Micheaux

(1935, 1h36, United States)

Presented by Cineteca di Bologna. Restored in 2021 by the George Eastman Museum and Cineteca di Bologna in association with The Film Foundation, Quoiat Films and Sky from a 35mm nitrate print in the SMU/Tyler Film Collection, SMU Libraries, deposited at the George Eastman Museum. Restoration performed at George Eastman Museum Film Preservation Services and L'Immagine Ritrovata laboratory

Followed by:

Oscar Micheaux - The Superhero of Black Filmmaking by Francesco Zippel

(1h20, Italy)

Presented by Quoiat Films, Sky.

Director Francesco Zippel in attendance

Orfeu Negro, Palme d’or in 1959

The Cannes Film Festival continues to explore the Palmes d'Or that have marked its history. This year, the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice will be revisited by Marcel Camus in Brazil and set to music by Antônio Carlos Jobim to bossa nova, samba and jazz. Dazzling.

Orfeu Negro (Black Orfeus) by Marcel Camus

(1959, 1h45, France / Brazil / Italy)

Presented by Solaris Distribution. Presented by Impex Films and Tigon Film Distributors. 4K digital restoration by Impex Films and Tigon Film Distributors with the help of the CNC, from the original 35mm negative. Original monophonic sound digitized from a viewing print which was also used as reference for color grading. Laboratory: Hiventy Classics. Theatrical distribution in France: Solaris Distribution, to be released in France by the second semester of 2021.

Rossellini and Les Cahiers du cinema

While the Cineteca di Bologna continues its visit to Rossellini's work, the Cahiers du cinéma celebrate their history in Cannes. André Bazin, the co-founder of the magazine was even a member of the Jury in 1954 and kept a diary recounting this experience.To celebrate the anniversary of the mythical monthly, what better way than to screen a film by Roberto Rossellini? He was assisted by François Truffaut, Bazin considered him a major figure in the same way as Renoir, Hitchcock or Hawks and this work signed by the Italian director was reviewed in the first issue in April 1951.

Francesco, giullare di Dio (Les onze fioretti de François d'Assise / The Flowers of St. Francis) by Roberto Rossellini

(1950, 1h27, Italy)

Presented by Cineteca di Bologna and The Film Foundation. Restored in 2021 by Cineteca di Bologna and The Film Foundation, in association with RTI-Mediaset and Infinity+, at L'Immagine Ritrovata laboratory. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

All the restored films of Cannes Classics 2021

La Drôlesse (The Hussy) by Jacques Doillon

(1978, 1h30, France)

Presented by Malavida. 2k scan and restoration made from the negative image, by Éclair Cinéma laboratory. Sound restored from the negative by L.E. Diapason. Restoration made by Gaumont with the support of the CNC. In preview of the retrospective « Jacques Doillon, jeune cinéaste » starting on November 3rd 2021.

Director Jacques Doillon in attendance

I Know Where I'm Going! (Je sais où je vais !) by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger

(1945, 1h32, United Kingdom)

Presented by The Film Foundation. Restored by the BFI National Archive and The Film Foundation in association with ITV and Park Circus. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. Additional support provided by Matt Spick.

Lumumba : la mort du prophète (Lumumba: Death of a Prophet) by Raoul Peck

(1990, 1h09, France / Germany / Switzerland / Belgium / Haiti)

Presented by The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project. Restored by the The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata/L’Image Retrouvée in collaboration with Velvet Film and supervised by Raoul Peck. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO – in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna – to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

Friendship's Death by Peter Wollen

(1987, 1h18, United Kingdom)

Presented by the British Film Institute (BFI). The 4K remastering by the BFI National Archive was from the original Standard 16mm colour negative. The soundtrack was digitised directly from the original 35mm final mix magnetic master track. The remastering was undertaken in collaboration with the film's producer, Rebecca O'Brien and cinematographer, Witold Stok.

Actress Tilda Swinton in attendance

Bal poussière by Henri Duparc

(1989, 1h33, Ivory Coast)

Presented by the CNC and the Henri Duparc Foundation. Restoration of the original 16mm negative image by the CNC laboratory. 2K scan. Color grading: Hiventy. Sound restoration from the original 16mm magnetic: L’Image retrouvée.

La Double vie de Véronique (The Double Life of Véronique) by Krzysztof Kieślowski

(1991, 1h38, France / Poland)

Presented by MK2. Restoration carried out by Hiventy from the original negative in 4K, supervised by director of photography Sławomir Idziak. Theatrical distribution in France by Potemkine.

Actress Irène Jacob in attendance

F for Fake (Vérités et Mensonges) by Orson Welles

(1973, 1h25, France/ Iran / Germany)

Presented by Les Films de L’Astrophore and La Cinémathèque française in collaboration with Documentaire sur grand écran. Restored by Les Films de L’Astrophore and La Cinémathèque française in collaboration with Documentaire sur grand écran, the Cinémathèque suisse and the Audiovisual institute of Monaco, with the support of Hiventy and the company foundation Neuflize OBC. Restoration work, image and sound made by the Hiventy laboratory, from the original negative and at L.E. Diapason Studio from the 35mm magnetic track.

Yashagaike (L'Étang du démon / Demon Pond) by Masahiro Shinoda

(1979, 2h04, Japan)

Presented by Shochiku. Digital remaster by Shochiku Co., Ltd. For the 4K remaster, the original 35mm negative was provided by Shochiku, sound remastered by Shochiku MediaWorX Inc. and the image remaster conducted by Imagica Entertainment Media Services, Inc. French distribution in theaters: Carlotta Films.

La guerre est finie (The War is Over) by Alain Resnais

(1966, 2h01, France)

Presented by Gaumont. First digital restoration in 4K presented by

Gaumont with the support of the CNC. Restoration made by Éclair Classics laboratory.

Échec au porteur (Not Delivered) by Gilles Grangier

(1957, 1h27, France)

Presented by Pathé. 4K scan and 2K restoration from the original safety negative (negative image, a standard dupe, a negative optical sound). Work made by L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory (Paris-Bologne). Restoration with the support of the Centre national du cinéma et de l'image animée (CNC).

Chère Louise (Louise) by Philippe de Broca

(1972, 1h45, France / Italy)

Presented by TF1 Studio. New 4K restored version by TF1 Studio and Warner Bros. from the original negative image. Digital work made by Vdm laboratory in 2021. Theatrical release to come: Les Acacias. Blu-ray collector release: Coin de Mire.

Napló gyermekeimnek (Journal intime / Diary for my children) by Márta Mészáros

(1983, 1h49, Hungary)

Presented by National Film Institute Hungary – Film Archive. The 4K digital restoration was carried out as part of ‘The long-term restoration program of Hungarian film heritage” of the National Film Institute – Film Archive. The restoration was made using the original image negatives and magnetic tape sound, it was carried out at the National Film Institute- Filmlab. The Digital grading was supervised by Nyika Jancsó, DOP of the film.

Director Márta Mészáros and DOP Nyika Jancsó in attendance

Až přijde kocour (Un jour, un chat / The Cassandra Cat) by Vojtech Jasný

(1963, 1h45, Czech Republic)

Presented by the Národní filmový archiv, Prague. 4K digital restoration based on the intermediate positive was done by L'Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in Bologna, 2021. The donors of this project were Mrs. Milada Kučerová and Mr. Eduard Kučera. Restored in partnership with the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival. French distribution: Malavida Films.

Actress Emília Vašáryová in attendance

Monanieba (Le Repentir / Repentance) by Tenguiz Abouladzé

(1984, 2h33, Georgia)

Presented by Georgian National Film Center. Interpositive: goskinofond. 4K scan and color grading: UPP Prague. Digital restoration, sound work and DCP: Studio Phonographe, Tbilissi. Funding: Georgian National Film Center.

Actor Avtandil Makharadze and screenwriter Nana Janelidze in attendance

Dan četrnaesti (Le Quatorzième jour / The Fourteenth Day) by Zdravko Velimirovic

(1960, 1h41, Montenegro / Serbia)

Presented by Crnogorska kinoteka, Podgorica & Jugoslovenska kinoteka, Belgrade. Digitally restored film from a 2K scan of the original black & white negative.

Il cammino della speranza (Le Chemin de l’espérance / The Path of Hope) de Pietro Germi

(1950, 1h45, Italy)

Presented by the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia – Cineteca Nazionale. Restored by Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia - Cineteca Nazionale from the original 35mm negative made available by

CristaldiFilm, completed by a dupe of the Cineteca Nazionale and optical sound of a positive by the Cineteca Nazionale.

Letter from an Unknown Woman (Lettre d'une inconnue) de Max Ophüls (1948, 1h27, United-States)

4k restoration from the original negative image and a 35mm positive. Sound restoration from the original negative. Work done by Technicolor for the image and Chace Audio by Deluxe for the sound, under the supervision of Paramount Pictures Preservation.

Theatrical release by La Rabbia, february 2022.

Mulholland Drive by David Lynch

(2001, 2h25, United-States)

Presented by Studiocanal. Restoration made by Criterion and Studiocanal from the original negative, scan in 4K at Fotokem, sound remastering from the original 5.1 sound. Sound and image were validated by David Lynch, in Cinéma and HDR format. French distribution by Studiocanal, with a theatrical release and a collector Blu-Ray UHD box set.

Cannes Classics 2021 : the documentaries

The Storms of Jeremy Thomas (Les Tempêtes de Jeremy Thomas) by Mark Cousins

(1h29, United Kingdom)

A yearly drive with the famous British producer Jeremy Thomas from London to Cannes, on his way to the... Festival de Cannes. A life in the service of cinema, a journey towards the discovery of new films and talents in the company of the cinephile director and author Mark Cousins.

Presented by David P. Kelly Films. Produced by David P. Kelly with Creative Scotland, Tim Macready and Visit Films.

Jeremy Thomas and Mark Cousins in attendance.

Satoshi Kon, l'illusionniste by Pascal-Alex Vincent

(1h21, France/Japan)

A subtle portrait of Japanese director Satoshi Kon by the specialist of Japanese cinema Pascal-Alex Vincent and a dive into a rich work. With interviews of the greatest Japanese, French and American directors inspired by his work.

Presented by Eurospace and Genco (Tokyo) in collaboration with Carlotta Films et Allerton Films (Paris).

Director Pascal-Alex Vincent in attendance

Buñuel, un cineasta surrealista by Javier Espada

(1h23, Spain)

Luis Buñuel and the Festival de Cannes is a great love story - the theater where the films of Cannes Classics are screened is called Buñuel itself. The documentary is filled with culture and is dedicated to the screenwriter, who was so close to the Spanish filmmaker and wrote many films with him, Jean-Claude Carrière. The documentary brilliantly explores the themes of the genius filmmaker.

Presented by Tolocha producciones.

Director Javier Espada in attendance

Montand est à nous (All About Yves Montand) by Yves Jeuland

(1h40, France.)

As an actor in Le Salaire de la peur (Grand Prix in 1953) or in La Guerre est finie presented this year, President of the Jury in 1987 (Maurice Pialat received the Palme d’or), Yves Montand has left a mark on the Festival de Cannes. Yves Montand has left a mark as strong in cinema as in music hall. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his birth and the 30th anniversary of his death, Montand est à nous is an exceptional documentary.

Written by Yves Jeuland and Vincent Josse.

Presented by Zadig Productions. Film produced by Zadig Productions, in coproduction with Diaphana Films, with the participation of France Télévisions.

Director Yves Jeuland and co-writer Vincent Josse in attendance,

The Story of Film: a New Generation by Mark Cousins

(2h40, United-Kingdom)

A major cinematic journey into pre-pandemic cinema. It all starts again with this magical, ambitious odyssey of unparalleled abundance in today's cinematic world. As a pre-opening of the Cannes Film Festival and announcing the edition full of surprises that is coming up.

Presented and produced by Hopscotch Films. Sales : Dogwoof.

Director Mark Cousins in attendance

Et j’aime à la fureur (Flickering Ghosts of Love Gone By) by André Bonzel

(1h50, France)

A very personal self-portrait of André Bonzel, co-director of the cult film C'est arrivé près de chez vous, based on images from amateur films that he has always collected, including some shot by his great-great-grandfather, a familiar face of the Lumière brothers. A unique, moving film that tells the story of a family cinephilia over several generations, set to music by Benjamin Biolay.

Produced by Les films du Poisson.

Director André Bonzel in attendance

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

Curtis Harrington was one of the few directors who began in the avant-garde and made the transition to feature narrative moviemaking. Like his friend Kenneth Anger, Harrington began by just picking up a camera and making movies, and both artists came out of the extremely particular world of the west coast art/poetry/cinema/music/occult world of the 40s and 50s. The last of Harrington’s non-narrative shorts, which had a life on the college 16mm circuit and in film societies, was The Wormwood Star (1956), a cinematic portrait of artist Marjorie Cameron, the widow of the rocket engineer and Aleister Crowley adept Jack Parsons. Cameron, who appeared with Harrington in Anger’s 1954 Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (along with Anaïs Nin and Anger himself), was called upon by Harrington to play the Water Witch in his first narrative film, Night Tide (1961, restored by the Academy with the help of The Film Foundation in 2007), about a sailor (Dennis Hopper) who falls in love with a boardwalk carnival performer (Linda Lawson) who he comes to realize is a real mermaid. I remember turning on a little black and white portable TV when I was young and being entranced by this homemade film, which seemed to emanate from its own planetary signal: related to a very particular strain of Hollywood cinema (under the sign of Josef Von Sternberg, on whose work Harrington had written a small book) but not quite of it, similar in spirit to the freshness of the French New Wave and Cassavetes’ Shadows but vastly different from both, Night Tide had its own trancelike, twilit magic. As was the case with so much in American cinema at the time, Roger Corman played a crucial role in getting Night Tide distributed.

Harrington went on to make many films in the very particular sub-genre spawned by the success of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? before he was drawn into what he called the vortex of episodic television. He was a key figure in American movies, a great raconteur and chronicler, and he worked and lived at the crossroads of multiple dynamic creative energies that exploded from the 50s through the 70s like a supernova. It still lights our way.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

Night Tide (1961, d. Curtis Harrington)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive with support from The Film Foundation and Curtis Harrington.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

“Cinema must be reinvented each time, and whoever ventures into cinema must also share in its reinvention.” I love this statement.

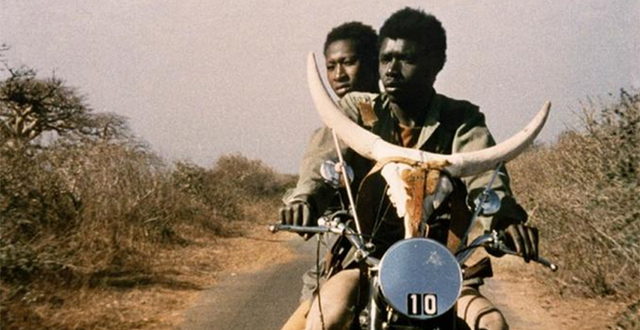

It was made in an interview by the Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty. Consider the statement in relation to Mambéty’s own cinema and to his Touki Bouki in particular (the film was restored by the World Cinema Project in 2008). On first viewing, his classic 1973 film—about a young couple from Dakar trying to make their way to a supposedly better life in France—might seem unorthodox in the extreme and even disconcertingly fragmented. But like all real artists, Mambéty had no interest in creating work that would go down easily.

The tools for moviemaking are now more easily accessible and much cheaper than they were when Mambéty started. But that means many things. Here in the United States, we are in a period where lots of stuff gets commonly and carelessly labeled as “movies.” It is now lazily expected that absolutely everything will go down easily, that moviemaking will bend like a reed to the demands of every new political program or trend, that the past can be ignored because somebody else will pay attention to it. Moviemaking is now like the internet—“democratized” without any actual investment in or discussion of the idea of democratization. This is a laissez-faire attitude that often amounts to a resigned belief in the technology itself, which will presumably chart its own course, which harmonizes perfectly with the interests of every CEO everyone loves to hate. In moviemaking as it stands, pretty much everything is being thrown against the wall and almost nothing is sticking. And that’s because there’s a lack of investment in the very idea of cinema itself, which means an investment in its past as well as its present. It’s a state of affairs that can’t go on forever, and the way forward can only be a rediscovery of the cinema’s past, through new eyes.

Mambéty is now a part of that past. He died far too soon, in 1998 at the age of 53. It was extremely difficult to get a film made in Africa during Mambéty’s lifetime, and it still is. Like Rossellini and Godard and Cassavetes, he pulled back the curtain and showed the world that moviemaking didn’t have to be a daunting and wildly expensive endeavor made only by trained craftsmen and artists. It could be made in a spirit of freedom with minimal elements. But, it had to be made, with a commitment to the cinema itself. Otherwise, it’s just more content.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

TOUKI BOUKI (Senegal, 1973, d. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Restored in 2008 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the family of Djibril Diop Mambéty. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.