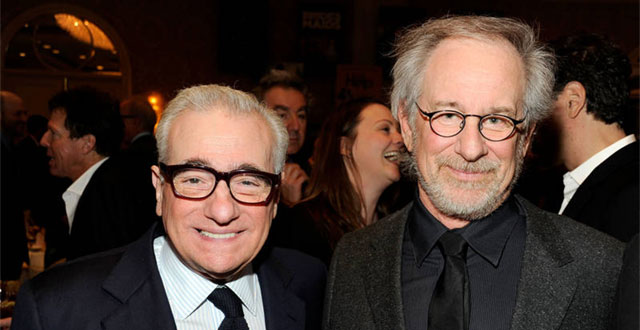

UNIVERSAL CITY, Calif., May 1, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- Universal Pictures and The Film Foundation announce a multi-year partnership to restore a handpicked selection of the Studios' classic titles. With this collaboration, Universal will fund the restorations as well as provide research and technical services. Through The Film Foundation, Martin Scorsese and Steven Spielberg will be personally involved in the process contributing their unique artistic expertise and historical knowledge throughout the restoration process. The restored versions will be screened at film festivals and archives around the world. The 2018 restoration slate includes the following:

- DESTRY RIDES AGAIN (1939, d. George Marshall)

- KILLERS, THE (1946, d. Robert Siodmak)

- KILLERS, THE (1964, d. Don Siegel)

- MY LITTLE CHICKADEE (1940, d. Edward Cline)

- WINCHESTER '73 (1950, d. Anthony Mann)

Additional titles will be announced in the coming months.

"I'm so excited by this partnership with Universal and the chance to continue what we started with the restoration of ONE-EYED JACKS," said Martin Scorsese. "Steven and I grew up with these pictures. We didn't just watch them—we absorbed them, they became part of our DNA. Neither of us can wait to get to work on WINCHESTER '73, the first of Anthony Mann's eight pictures with James Stewart, and on both versions of Hemingway's THE KILLERS: two different pictures from two different eras, both of them classics. And there's so much more to choose from in the Universal library. We're all thrilled to be making these treasures of American cinema available to audiences once again."

"I'm delighted to be working with Marty, The Film Foundation and Universal on this project," said Steven Spielberg. "It's a great opportunity to not only restore a remarkable selection of films, but also to make them available to audiences the way they were meant to be seen. The focus and scope of this project will result in valuable contributions to the preservation of our film history."

"We are very happy to deepen our long relationship with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg and The Film Foundation," said Michael Daruty, Senior Vice President, Global Media Operations Management for NBCUniversal. "These films represent some of the landmark titles in Universal's rich history and library."

This restoration partnership marks another step in Universal's film restoration initiative announced during the company's Centennial in 2012. More than 70 titles have been fully restored including All Quiet on the Western Front,The Birds, Buck Privates, Dracula (1931), Drácula Spanish (1931), Frankenstein, Jaws, Schindler's List, Out of Africa,Pillow Talk, Bride of Frankenstein, The Sting, To Kill a Mockingbird, Touch of Evil, Double Indemnity, High Plains Drifter, Holiday Inn, Spartacus, King of Jazz, Cleopatra (1934), Duck Soup, and One-Eyed Jacks. In 2015, Universal launched their silent film initiative. Since then, the company has restored 15 titles such as Outside the Law, Sensation Seekers, The Last Warning, Straight Shooting, and The Man Who Laughs.

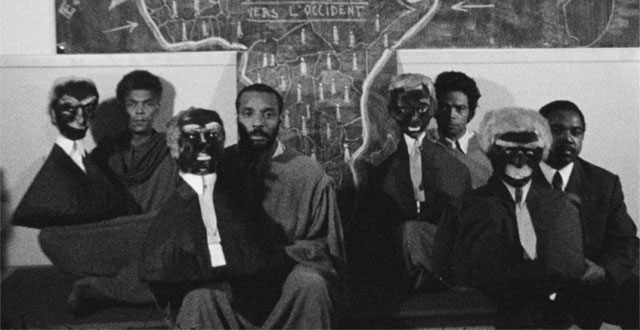

The Film Foundation is a nonprofit organization established in 1990 dedicated to protecting and preserving motion picture history. By working in partnership with archives and studios, the foundation has helped to restore over 800 films, which are made accessible to the public through programming at festivals, museums, and educational institutions around the world. The Film Foundation's World Cinema Project has restored 31 films from 21 different countries representing the rich diversity of world cinema. The foundation's free educational curriculum, The Story of Movies, teaches young people - over 10 million to date - about film language and history.

Universal Pictures is a unit of NBCUniversal, one of the world's leading media and entertainment companies in the development, production, and marketing of entertainment, news, and information to a global audience. NBCUniversal owns and operates a valuable portfolio of news and entertainment television networks, a premier motion picture company, significant television production operations, a leading television stations group, world-renowned theme parks, and a suite of leading Internet-based businesses. NBCUniversal is a subsidiary of Comcast Corporation.