News

Film Foundation launches 'Portraits of America' program to teach students visual literacy

Daniel Eagan

At a time when moving images dominate our lives, the idea of "visual literacy," the ability to read and understand images, has taken on a greater urgency. That's one of the impulses behind “Portraits of America: Democracy on Film,” a new program from The Film Foundation, in partnership with the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME).

Offered free of charge to elementary and high schools, “Democracy on Film” is made up of eight modules addressing different aspects of the democratic experience, including immigration, labor, civil rights and the press. Within each module, scholars, educators and filmmakers examine movies that reflect American democratic ideals.

The titles extend from 1917 to 2006, and include comedies, documentaries, drama, science fiction, horror, cartoons, historical fiction, independent films and Hollywood blockbusters. Accompanying the curriculum are a teacher's guide, a reader for students, PowerPoint presentations, and a DVD (which can also be streamed) that includes film excerpts and additional material.

Speaking on a panel at New York City's DGA Theater, award-winning director and Film Foundation founder Martin Scorsese noted, "We already teach our students to be critical thinkers, now we have to start teaching them to be critical viewers as well."

For Scorsese, it's crucial that young people "learn to sort the differences between art and pure commerce, between cinema and 'content,' between a sequence of individually crafted images and a sequence of factory-manufactured, mass-produced images engineered only to grab your attention and sell you something."

Other panelists included Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden; author, professor and film historian Jeanine Basinger; curriculum author Catherine Gourley; and Lee Saunders, president of AFSCME.

"This is an opportunity for my union to put forth the importance of labor history, in the context of American democracy," Saunders said. "Whether it's women's marches or civil-rights marches, things of that nature, struggle has always been a part of our history. We've got to understand that struggle, make that connection with young people so they understand their history. Improving our democracy is a duty we all share."

According to Basinger, "We are living in a world of moving images. Outside the classroom, the moving image is the major form of communication for these young people, a major source of their learning about what's going on in the world, a major source of the way the world speaks to them. It's also the way they communicate with each other.

"The young people of America are simply not educated if they cannot understand how to see moving images, how to interpret them, how to unlock their subtexts and messages, how to read them for an understanding of the country they live, warts and all."

Gourley, the author of more than 30 books, began working on the“Story of Movies” program in 2005. For her, one of the primary goals of “Democracy on Film” is to teach students "how to read a film on multiple levels. Most obviously, what is the story about, what is its narrative structure, what does it mean? But also how to read a film as a work of art. Equally important is learning to read a film as a historical and cultural document."

Dr. Hayden noted that the curriculum will be added to the “Teaching with Primary Sources” curriculum, which focuses on showing teachers and students how to work with original documents. Through the extensive holdings of the Library of Congress, Hayden and her staff were able to supplement film titles with contemporary reviews, political cartoons and interviews that help explain their times.

These materials will be especially useful with some of the titles in the program, like Salt of the Earth, a 1954 independent film about a strike in New Mexico.

"Whatever you may think of the film, Salt of the Earth is a really interesting example of making a picture outside the system," Scorsese said. "They made that film with no help at all because they needed to. What is it all about? It's about human dignity, freedom. This is what we have to fight for."

"One of the things we tried to do with a film like Salt of the Earth is provide primary source materials that explore the tenor of the time," Gourley added. "How people reacted to it at the time. Salt of the Earth was condemned on the floor of Congress, so we include that speech from that congressman, and we allow the students to read it and ask them, what do you think?"

"It's humanizing issues to make you think further than just slogans, and make you aware of things in your own life that you maybe haven't thought about," Basinger agreed. "And with a film like The Immigrant [made by Charlie Chaplin in 1917], there's no great political leveler like humor."

Salt of the Earthis one of five titles in a module on "The American Laborer." Others include Barbara Kopple's Harlan County U.S.A. (1976), about a coal strike in Kentucky, and Martin Ritt's Oscar-winning union drama Norma Rae (1979).

"I learned a lot about unions," Scorsese recalled. "My parents worked in the garment district, my mother was a seamstress. This was before the unions, the sign was: 'You don't come in Sunday, don't come in Monday.' That's not even about hardship, about treatment. Somebody's got to get organized. Then you go from there. A film I'm making now [The Irishman], one of the characters is Jimmy Hoffa. Whatever may have happened in the Hoffa story, he was still on those picket lines getting his head busted."

The next program from the Film Foundation's “Story of Movies” will cover one of the country's enduring themes: “The American West and the Western Film Genre.” It will be released later this year.

"Division, conflict and anger seem to be defining this moment in culture," Scorsese summed up. "I learned a lot about citizenship and American ideals from the movies I saw. Movies that look squarely at the struggles, violent disagreements and the tragedies in history, not to mention hypocrisies, false promises. But they also embody the best in America, our great hopes and ideals."

Martin Scorsese’s New Film Course: ‘Portraits of America’ Teaches Democracy Through Chaplin, Coppola, and More

Zack Sharf

"We have to teach our students to be critical viewers," Scorsese said during a press conference announcing the new film curriculum.

Martin Scorsese and his nonprofit organization The Film Foundation have announced their brand-new film curriculum, “Portraits of America: Democracy on Film.” The curriculum is the latest addition to the group’s ongoing film course “The Story of Movies,” which aims to teach students how to read the language of film and place motion pictures in the context of history, art, and society. Both “Democracy on Film” and the course are completely free for schools and universities.

“Portraits of America: Democracy on Film” is broken down into eight different sections, all of which include in-depth looks at some of the most important American films ever made, from Chaplin to Ford, Coppola, Spielberg, and ultimately Scorsese himself. The program is presented in partnership with AFSCME. Scorsese announced the curriculum at a March 27 press conference in New York City.

Per Scorsese, the “Portraits of America” course features eight modules, and within each are four to five chapters focusing on specific films for in-depth study. “The American Woman” module, for instance, suggests Ridley Scott’s “Alien” for conversation, while “The Immigrant Experience” includes” The Godfather.”

An outline of the latest curriculum is below. Visit “The Story of Movies” official website for more information.

Module 1: The Immigrant Experience

Introductory Lesson: From Penny Claptrap to Movie Palaces—the First Three Decades

Chapter 1: “The Immigrant” (1917, d. Charlie Chaplin)

Chapter 2: “The Godfather, Part II” (1974, d. Francis Ford Coppola)

Chapter 3: “America, America” (1963, d. Elia Kazan)

Chapter 4: “El Norte” (1983, d. Gregory Nava)

Chapter 5: “The Namesake” (2006, d. Mira Nair)

Module 2: The American Laborer

Introductory Lesson: The Common Good

Chapter 1: “Black Fury” (1935, d. Michael Curtiz)

Chapter 2: “Harlan County U.S.A.” (1976, d. Barbara Kopple)

Chapter 3: “At the River I Stand” (1993, d. David Appleby, Allison Graham and Steven Ross)

Chapter 4: “Salt of the Earth” (1954, d. Herbert J. Biberman)

Chapter 5: “Norma Rae” (1979, d. Martin Ritt)

Module 3: Civil Rights

Introductory Lesson: The Camera as Witness

Chapter 1: King: A Filmed Record…Montgomery to Memphis (1970, conceived & created by

Ely Landau; guest appearances filmed by Sidney Lumet and Joseph L.

Mankiewicz)

Chapter 2: “Intruder in the Dust” (1949, d. Clarence Brown)

Chapter 3: “The Times of Harvey Milk” (1984, d. Robert Epstein)

Chapter 4: “Smoke Signals” (1998, d. Chris Eyre)

Module 4: The American Woman

Introductory Lesson: Waysof Seeing Women

Chapter 1: Through a Woman’s Lens: Directors Lois Weber (focusing on “Suspense,” 1913 and

“Where Are My Children,” 1916) and Dorothy Arzner (“Dance, Girl, Dance,” 1940)

Chapter 2: “Imitation of Life” (1934, d. John M. Stahl)

Chapter 3: “Woman of the Year” (1942, d. George Stevens)

Chapter 4: “Alien” (1979, d. Ridley Scott)

Chapter 5: “The Age of Innocence” (1993, d. Martin Scorsese)

Module 5: Politicians and Demagogues

Introductory Lesson: Checks and Balances

Chapter 1: “Gabriel Over the White House” (1933, d. Gregory La Cava)

Chapter 2: “A Lion is in the Streets” (1953, d. Raoul Walsh)

Chapter 3: “Advise and Consent” (1962, d. Otto Preminger)

Chapter 4: “A Face in the Crowd” (1957, d. Elia Kazan)

Module 6: Soldiers and Patriots

Introductory Lesson: Movies and Homefront Morale

Chapter 1: “Sergeant York (1941, d. Howard Hawks)

Chapter 2: Private Snafu’s Private War—three Snafu Shorts from WWII

Chapter 3: “Three Came Home” (1950, d. Jean Negulesco)

Chapter 4: “Glory” (1989, Edward Zwick)

Chapter 5: “Saving Private Ryan” (1998, d. Steven Spielberg)

Module 7: The Press

Introductory Lesson: Degrees of Truth

Chapter 1: “Meet John Doe” (1941, d. Frank Capra)

Chapter 2: “All the President’s Men” (1976, d. Alan J. Pakula)

Chapter 3: “Good Night, and Good Luck” (2005, d. George Clooney)

Chapter 4: “An Inconvenient Truth” (2006, d. Davis Guggenheim)

Chapter 5: “Ace in the Hole” (1951, d. Billy Wilder)

Module 8: The Auteurs

Introductory Lesson: Film as an Art Form

Chapter 1: “Modern Times” (1936, Charlie Chaplin)

Chapter 2: “The Grapes of Wrath”(1940, d. John Ford)

Chapter 3: “Citizen Kane” (1941, d. Orson Welles)

Chapter 4: “An American in Paris” (1951, d. Vincente Minnelli)

Chapter 5: “The Aviator” (2004, d. Martin Scorsese)

Additional reporting by Eric Kohn.

‘Night of the Living Dead’: Zombies Restored to Their Full Beauty

Glenn Kenny

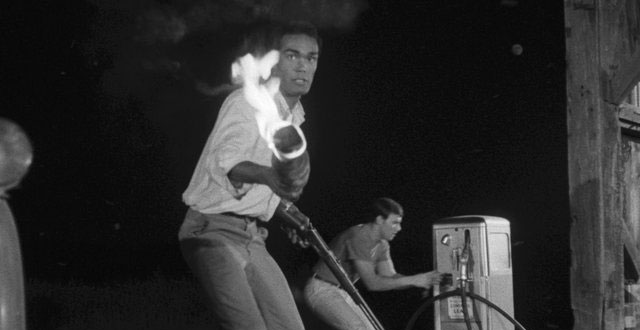

On Feb. 13, just in time for Valentine’s Day, the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck debuted “Night of the Living Dead,” George A. Romero’s 1968 horror classic. The posting is notable for several reasons.

For one thing, if you stream a lot of video, you know that “Night of the Living Dead” is everywhere. There are three versions, including a colorized one, free to Amazon Prime members. So you may well ask why the FilmStruck/Criterion Channel offering is a big deal. It’s because the version appearing on the site is a new restoration from the film’s original negative, produced by the Film Foundation (the preservation nonprofit founded by the director Martin Scorsese) and the Museum of Modern Art, which put “Night of the Living Dead” in its permanent collection. The restored film was shown in November 2016 at MoMA and later in repertory and art house theaters all over the country.

For another, this is the second time Criterion has put up a film on the site the same day as its release on physical media, in this case a two-disc Blu-ray on the Criterion Collection label. (The first time this happened was with “Desert Hearts,” released and posted last November.)

Some skeptics online who haven’t seen the restoration ask “how good can the new version look?” After all, “Living Dead” is one of the original low-budget horror movies that morphed into a classic. The answer lies in part with just how bad the versions you can watch on Amazon Prime look. There’s one with a “Fisher Klingenstein Films” logo before the opening shot. The image is blurry, with the whites far too bright, washed-out and lacking in detail. A “50th Anniversary” edition, touting the movie as “Now Available in 1080p High-Definition-2K HD transfer from a rare film print” may well be as advertised. Yet however “rare” the print from which the version was scanned, it wasn’t in very good shape. A lot of scratches and blotches, and overly high contrasts that deepen the blacks into nothingness while distorting the whites. We shall not even speak of the colorized version.

These various iterations exist because the movie’s original distributor failed to copyright it. Once it went into the public domain, anyone with a print of the movie could distribute it anywhere, produce video versions, and more, free. The creators of the movie didn’t make any money. The Film Foundation and MoMA allowed Image Ten, the original company behind the film, founded by the director, Mr. Romero, the producing brothers Gary and Russell Streiner, and the writer John Russo, among others, to register a copyright for this restoration. And Janus Films and its sister company Criterion licensed the movie from Image Ten. So this is the only edition of the film that yields revenue to all its original creators.

And it does, in fact, look amazing. “Night of the Living Dead” broke new horror ground with its story of a group of strangers trying to work together to fend off a mysterious attack by risen corpses determined to feast on the living. Its influence is felt on just about every zombie movie since. Yes, it was a low-budget picture, but it was made by artists who knew what they were doing.

The restoration doesn’t make the movie look slick, but it gets the true, sharp contrasts of the cinematography. This imbues much of the movie with what was then recognized as a documentary-style realism, which bolsters the emotional power of the tale. When I interviewed Mr. Romero about the restoration, he said, with affection in his voice: “The movie’s pimples do show. There’s a copy of the script visible in one of the frames! I won’t tell where. It will be a little challenge for the fans to spot it.”

On a recent viewing of the restoration, I was able to spot it — although for a while I didn’t think I would, so engrossed was I, even after probably dozens of viewings. I won’t reveal its exact whereabouts, except to say it’s after the movie’s 75-minute mark.

And the FilmStruck/Criterion Channel presentation also offers some supplements that are on the Blu-ray package. There’s a nearly half-hour video featuring the filmmakers Frank Darabont, Guillermo del Toro and Robert Rodriguez,

expounding on the movie’s influence. You can also watch “Night of Anubis,” a 16-millimeter “work print” of “Living Dead” under a different title. It’s raggedy looking and only minimally different in content to the finished film, but it’s of interest to fans who want to peer into the filmmakers’ process; Russell Streiner, one of the film’s producers, who also plays the memorable role of Johnny, who has the car keys, gives a thorough introduction to the supplement.

So yes — the FilmStruck/Criterion Channel “Night of the Living Dead” is the one to see. And it is, in the parlance of Criterion, “director approved” — Mr. Romero, who died in July 2017, did sign off on this version. You will not be disappointed to see the movie as he intended.

A version of this article appears in print on February 18, 2018, on Page AR14 of the New York edition with the headline: George Romero’s Vintage Zombies Are Resurrected.

Interview: Gina Telaroli on Republic Rediscovered

Caroline Golum

The Museum of Modern Art's hotly anticipated series Martin Scorsese Presents Republic Rediscovered: New Restorations from Paramount Pictures begins this week with a lineup designed to enrapture and entice! These long-unavailable titles will make their triumphant return to the big screen in handsome new restorations, the product of a years-long effort spearheaded by Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation and Paramount Studios.

Unfamiliar with Republic Studios? To bring you up to speed, Screen Slate chewed the fat with Gina Telaroli, filmmaker, woman-about-town, and video archivist of Scorsese's Sikelia Productions. Her handiwork can be seen in the series trailer and its accompanying photo essay.

Screen Slate: I think it's safe to assume that Screen Slate readers are familiar with the concept of "Poverty Row" in general, but they might not know where studios like Republic Pictures fit into the larger Hollywood ecosystem. For the uninitiated, can you tell us a little bit about where Republic Pictures stood in relation to other, bigger studios like MGM, Warner Brothers, and Paramount?

Gina Telaroli: In 1935, Herbert J. Yates, a former Tobacco employee who was born of a bible salesman, combined six smaller poverty row studios—Monogram, Mascot, Majestic, Liberty, Chesterfield, and Invincible—and thus, Republic Pictures was born. The kind of content they produced was largely based on what the six studios had already been doing. At first there was a lot of independence and more resources for all of the players, but Yates eventually began to increase his authority, and as time went on it really started to become one studio that yielded to Yates’s vision. Monogram pulled out pretty quickly, and eventually the previous owners of the smaller studios, who had stayed on to work for Republic, pretty much all left, too. I think what sets them apart from the larger studios is possibility. Every time I watch a new Republic film, it just feels like there is a larger chance to see something different or weird or to discover something or someone new. When you’re making smaller genre films, directors can often work in new ideas or try new things, because the formula still remains intact and makes the film viable. The history of the studio is fascinating though, and for anyone who is interested, I recommend tracking down Jack Mathis’s masterwork Republic Confidential: Volume 1: The Studio , an insanely in-depth book about every possible aspect of the studio. Regardless of one’s interest in Republic, it’s an amazing book about what it takes to make movies, then or now. It might just be the best guide to filmmaking out there.

I've Always Loved You (Frank Borzage, 1946)

Within the Poverty Row tier, Republic held a unique distinction—the quality of the films seemed to be a bit higher than the "competition," and they routinely nabbed well-known names: directors like Lewis Milestone and Frank Borzage, and actors like Myrna Loy, Joan Crawford, and John Wayne, to name a few. How did they manage to secure this kind of talent, and what do you think made Republic such an attractive studio to work for?

In the 50s you started to have a lot of big stars who were starting to get older, past their Hollywood prime, acting in B movies, genre fare, etcetera. They weren't young enough for a lot of roles at the major studios, and the smaller studios and independent producers saw an opportunity to have an impressive name attached to their project. In August we’ll be screening a great Ray Milland movie called A Man Alone that he not only stars in, but it was also his first directorial effort. (He also directed Lisbon for the studio.) Beyond Republic, you had someone like Benedict Bogeaus basically building an entire output around this concept with the series of films he made with Allan Dwan, who went straight from making films at Republic to making them with Bogeaus.

Other cases are a little more individual, though it often came down to Yates wanting to raise the profile of the studio beyond their serials and other standard genre fare. Borzage was likely swayed by a deal that would allow him a large amount of creative freedom, which resulted in two of his strangest and most “Borzage” films: the obsessive I’ve Always Loved You (February 10 and 14) and the bizarre Moonrise(screening in August). The Red Pony (February 4 and 12) gave Milestone another chance to work with John Steinbeck and Aaron Copland and was actually pretty early in Mitchum’s career. Likewise, when John Wayne started acting for Republic, he wasn’t the big star we know him as today. In the end, not unlike today, I think a lot of it simply came down to going where the work was, whether it was any work, or simply the opportunity to do a more specific kind of work.

Hellfire (R.G. Springsteen, 1949)

Republic Pictures was based in Studio City, and they had a ranch in Encino. (Disclosure: both of these places are in the San Fernando Valley, where I am from!). With this in mind, it's not surprising that their filmography features a wagon-load of Westerns. Other than the real estate, why do you think Republic made so many oaters? And, as an aside, how does their output in this genre stack up against the other studios—both in Hollywood proper and on Poverty Row?

I've never been a good numbers person in terms of quantity, and I’m sure some wonderful person out there has already done that math, but to look at a different aspect of the word, I do think Westerns used to be a known quantity and have a kind of built in audience, which studios like Republic, who are producing small movies quickly, really rely on. What I've noticed watching so many of the Republic Westerns over the past few months is that often the Republic directors used genre to allow them to make some pretty interesting pictures. When people are wearing cowboy hats and there are gun battles, you can do a lot with the characters’ interpersonal relationships, because there's always a level of remove. You can go a little deeper and darker with explorations of human behavior, because on the surface, it’s always a fun cowboy movie with a woman who sings in a saloon, etcetera. The Plunderers(February 5 and 11) and Hellfire (February 2, 6, and 13), two of my favorites in the series, are two prime examples of this.

The Plunderers (Joseph Kane, 1948)

Can you tell us about the series—how it came about, and what the process has been like restoring and programming these titles? I know it's the product of an extensive effort, spearheaded by the Film Foundation. Why dedicate the time and resources to restoring these films? What about them makes them so special?

It's been a labor of love between all the parties involved: Paramount Pictures, MoMA, The Film Foundation, and, of course, Marty. Paramount owns the Republic catalog, and the work they’ve done on these preservations is nothing short of incredible. So many of these films have only been available to the public in extremely subpar conditions and mostly illegally (YouTube or taped off of television years ago), and to see these new transfers has truly been a revelation to me. I kind of can’t get over how lucky we all are to have a studio putting so much care into this kind of catalog: one of B-movies, westerns, noirs, serials, and so on.

We’re also so lucky to have a film program at MoMA that remembers that films from the 30s, 40s, 50s and earlier are the very definition of modern art. So often they are cast aside as old and outdated and out of touch in the public consciousness, but in the context of art, they are extremely modern, and that is especially true of these Republic films—from the special two-strip color process they used for five years to the kind of plots the were dealing with. I think if people approached them in this context they’d be really wowed by everything that is going on in them.

Then there is the heroic work of The Film Foundation and Marty. Along with their World Cinema Project, they do such tireless work to restore such a vast variety of films, from well-known classics to Edgar Ulmer rarities to things like their most recent partnership on the African Film Heritage Project to something like Juan Bustillo Oro’s Dos monjes that is currently screening in To Save And Project. And then there’s Marty. What’s so special about this series is that it isn’t just a random assortment of films or an academic look at an old Hollywood studio, but it’s a selection of films that have been a part of his life, that he has watched again and again over the years. The selection is definitely representative of the studio, but they’re also coming from the specific point of view of someone who really knows and cares about the films and that kind of filmmaking in general. There are some real treasures in the series, and I can’t wait for more people to be able to see them!

Accused of Murder (Joseph Kane, 1956)

BONUS QUESTION: What are you favorite titles in this series? Screen Slate readers face a glut of options on any given night, so what should our readers prioritize when staring down such a comprehensive line-up?

Honestly, everything is pretty great. I know there’s a ton of stuff screening in February, so I would say just go whenever you can! But the real discoveries for me have been house director Joseph Kane’s The Plunderers (February 5 and 11) and Accused of Murder (February 5 and 7); John H. Auer’s Angel on the Amazon (February 3 and 7) and The Flame (February 3 and 6); and the religious trilogy of Driftwood (February 2 and 8), Hellfire (February 2, 6, and 13), and Stranger at My Door (February 10 and 12). Basically, all of the films I did a series of image essays on, which can be seen at http://republicpictures.tumblr.com.