News

Guillermo del Toro and Martin Scorsese Celebrate the ‘Extraordinary Artistry’ of ‘The Greatest Story Ever Told’

Jim Hemphill

The directors paid tribute to George Stevens' 1965 biblical epic before the Academy Museum's premiere of a new restoration overseen by Amazon MGM Studios and Scorsese's Film Foundation.

On Saturday, the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles presented the world premiere of a new 4K restoration of George Stevens‘ “The Greatest Story Ever Told” (1965), one of the most ambitious and experimental of all Hollywood epics. Director Martin Scorsese, whose Film Foundation was instrumental in restoring the film (and whose “The Last Temptation of Christ” is the only biblical epic that rivals “The Greatest Story” in its audacity and complexity), provided a video introduction in which he celebrated Stevens’ masterpiece as the summation of his work.

“ The film was shot in Ultra Panavision 70 with lenses that yielded an aspect ratio of 2.76 to 1, and it was breathtaking,” Scorsese said. “But it wasn’t just the size of the image, it was the imprint of the man behind the camera who knew how to fill that frame, how to compose it. And composer seems like the right word to describe George Stevens and the extraordinary level of artistry he reached at that point in his life and career.”

Scorsese explained that when Stevens came back from World War II, his work took on a new sense of purpose and urgency in powerful works like “A Place in the Sun,” “Shane,” “Giant,” and “The Diary of Anne Frank.” “He began to pay very close attention to evil, to the greed and the hatred and the raw murderous violence that can overtake us all if we don’t all pay attention,” Scorsese said. “Those pictures are grand cinematic canvases, but they’re also urgent warnings to take care of our goodness and our love.”

Although Stevens was not a particularly religious man, he saw in Jesus Christ a way to explore those themes on their grandest scale. “‘The Greatest Story Ever Told’ is the summation,” Scorsese said. “It’s the final movement of Stevens’ multi-picture symphony. Stevens chose to enact the story on a scale of mythic grandeur and timeless immensity. This picture was years in the making at a cast of thousands.” It also felt of a piece with Stevens’ Westerns thanks to the unusual choices the director made when it came to locations.

“It was set against the backdrop of the American West in locations that we normally associate with Westerns,” Scorsese said. “Death Valley, Moab, Utah, Pyramid Lake in Nevada. It’s an extraordinary idea and it was really controversial because most biblical epics up to that time been shot somewhere near the Middle East or in the Middle East.” Scorsese noted that the film was part of a trend that included Nicolas Ray’s “King of Kings” and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “The Gospel According to St. Matthew” that brought a new immediacy to the story of Jesus Christ. “They turned away from the conventions of the period.”

Scorsese added that the production encountered “one calamity after another” and ultimately didn’t fully realize Stevens’ vision. “ Nevertheless, Stevens put everything he had into the telling of the story of Jesus and you could feel it from the first frame to the last,” Scorsese said. “He wanted to embody the tragedy and the redemption of humanity on every level. In a way, his ambitions were so grand that it wasn’t possible to realize them fully, but the sheer intensity and artistry of the picture is moving all on its own. There’s nothing else quite like it.”

Stevens’ son, filmmaker George Stevens Jr., worked on the restoration with Amazon MGM Studios and the Film Foundation and appeared in person at the Academy Museum to introduce Guillermo del Toro, a lifelong Stevens enthusiast and Film Foundation board member who was present to deliver a 20-minute lecture on “The Greatest Story Ever Told” before the film. As a Catholic raised in Mexico, del Toro estimated that he had seen “The Greatest Story” over 20 times — and he sat with the audience in the Academy Museum to watch it again in its exquisite new restoration.

Del Toro provided rich historical context for the film, describing Stevens’ path through several epochs of filmmaking. “He lived through every era of cinema,” del Toro said before exploring Stevens’ innovations during the silent period, his wartime documentary work, his seminal post-war American epics, and the influence he had on the New Hollywood. This last topic was where del Toro’s lecture was most revelatory, as he explained why the perception of Stevens as a staid classical filmmaker is dead wrong, and that in fact Stevens was a modernist who influenced one of the most groundbreaking films of the 1960s, “Bonnie and Clyde.”

“I want to make the case today that this man influenced the New American Cinema,” del Toro said. “He influenced Martin Ritt, Warren Beatty, Terrence Malick and many more.” Del Toro gave the example of Warren Beatty studying the sound mix of “Shane” and applying its principles to the climactic shoot-out in “Bonnie and Clyde.” “Beatty was the first man that noticed ‘Shane’ was a modern film by a modern master. Stevens insisted that the percussion, the brutality of a gunshot overpowers with its violence, and Beatty understands that this is a bold decision, a bold technique.”

In discussing “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” del Toro insightfully drew parallels between Stevens’ age and our own, both in terms of world politics and upheaval in the film industry. “ His canvas became Ultra Panavision 70, with a spherical system that gave him extra space,” del Toro said. “When he shot this movie, there was a battle between TV and cinema — we’re there again — and the battle was how to get people into theaters. One of the things was spectacle. The larger formats were getting people into theaters, but very few directors really knew how to use it and how to use it expressively.”

Del Toro added that Stevens used the vast potential of the Ultra Panavision 70 frame as a tool to examine his themes with sweep and intensity. “You can find out more about an artist by their art than by sharing space and time with them,” del Toro said when explaining that “The Greatest Story Ever Told” expressed Stevens’ profoundly humanistic point of view. “This is a time and a generation that didn’t signal virtue, they practiced it. They didn’t tell you who they were, they demonstrated who they were.”

“The Greatest Story Ever Told” represented a demonstration of all that Stevens had learned and felt about good and evil since liberating Dachau concentration camp during his time in the service, an experience that informed the film he made right before “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” “The Diary of Anne Frank.” “One of the questions he was trying to grapple with was that no one group crucified Jesus,” del Toro said. “We all crucified Jesus. Stevens said there was no them, it was us.”

Yet for del Toro, what stands out about “The Greatest Story Ever Told” and the rest of Stevens’ body of work is its hopefulness and faith. “He realized that art and narrative have such a high calling to tell us what we are and who we are, and that compassion and decency are our superpowers,” del Toro said. “Don’t let them lie to you that hatred is our superpower. It diminishes us, and Stevens understood this.”

Stevens only made one film after “The Greatest Story Ever Told,” the Warren Beatty vehicle “The Only Game in Town,” which got made due to Beatty’s reverence for the master director. “What would George Stevens have done after this film if given another chance at the canvas he was grappling with?” del Toro asked before closing his lecture with the memory of watching “The Greatest Story Ever Told.” “If you grow up Mexican, every Easter you saw this movie. It’s Saturday, but let’s have Easter together.”

“The Greatest Story Ever Told” premiered at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, where Guillermo del Toro presented this year’s “George Stevens Lecture on Directing”— the museum’s ongoing lecture series about the art of filmmaking. For information on future museum events, visit their website.

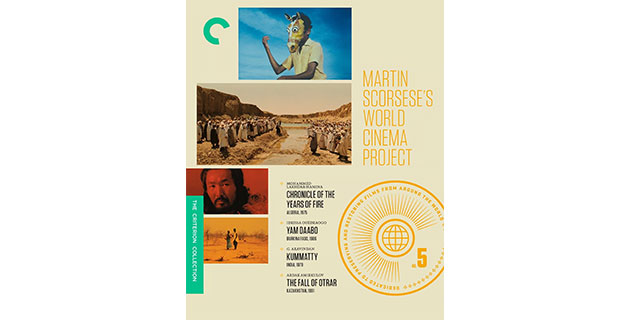

Blu-ray Review: ‘Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 5’ on the Criterion Collection

Jake Cole

Criterion offers another slew of neglected classics their much-deserved moment in the sun.

The Criterion Collection’s latest bundle of films restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project is bookended by two of the largest spectacles in the series to date: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina’s Palme d’or-winning Chronicle of the Years of Fire, which reorients the visual language of a David Lean epic around the perspective of a colonized people, and Ardak Amirkulov’s The Fall of Otrar, which was made off and on for a period of years during the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Beginning in the lead-up to the Second World War and carrying through to the period of the postwar Algerian independence movement and eventual war, Chronicle of the Years of Fire centers its vast canvas on Ahmed (Yorgo Voyagis), who uproots his family from a drought-ravaged village to Algiers, where he becomes radicalized by the exploitation he suffers at the hands of French colonists. Lakhdar-Hamina arranges gorgeous but bleak vistas of arid landscapes before slowly shifting into staged recreations of guerilla warfare or French reprisals that focus less on the action itself than the aftermath of bodies littering streets. Galvanizing in its depiction of tribal conflict giving way to solidarity against a common enemy, the 1975 film nonetheless never loses sight of the immense cost of gaining one’s freedom.

The Fall of Otrar details the story of one of Genghis Khan’s most brutal conquests: the eradication of the Khwarazmian Empire after its shah recklessly executed the Mongol’s envoys. Co-written by maverick Russian filmmaker Aleksei German and his wife and frequent collaborator, Svetlana Karmalita, Amirkulov’s 1991 film shares many of that director’s stylistic and thematic preoccupations, as evidenced by the swooning, dreamy long takes and garishly sensual evocation of the filth and fury of pre-modern life.

For all the immensity of its production design and its impressively mounted battle scenes, the film often conveys an intense claustrophobia befitting the siege campaign that brought the walled city of Otrar to its knees. It’s also one of the greatest movies ever made about irreconcilable culture clash, of what happens when two civilizations have such radically different values that neither can comprehend the other and sees annihilation as the only logical response.

Sandwiched between these colossal works are two comparatively shorter features: Idrissa Ouédraogo’s 1987 debut, Yam Daabo, and G. Aravindan’s Kummatty, from 1979. Yam Daabo’s title translates to “The Choice,” a brutal and multivalent irony considering the hardships on display, which range from economic desperation to the false promise of urban prosperity for rural transplants to the violently possessive tug of war by two suitors for the same woman.

Ouédraogo is anti-lyrical in his approach, presenting this harsh land in stark cuts and minimally moving shots and filling the soundtrack with the sounds of hoes tilling rocky soil and the occasional snap of gunfire. And yet, the film also takes care to point out the grace that people extend to each other even at the height of conflict. A handshake between fathers dissipates the tensions raised by their competing teenage sons, and elsewhere, a show of humanity from a seemingly lost soul toward an old friend inspires the latter to return to a home he abandoned.

The fabulistic Kummatty follows a Pied Piper-esque magician (Ambalappuzha Ravunni) who charms local children into obedience and devotion. Against expansive landscape shots of the mountainous, tropical southern Indian state of Kerala, Aravindan’s film gradually induces a sense of the uncanny using in-camera techniques. Opening the aperture a few extra stops in daytime scenes, Aravindan and cinematographer Shaji N. Karun overexpose the images to make the sky appear almost blindingly bright and hyperreal. And when the sorcerer starts weaving his magic, quick edits are used to convey the effect of his transfiguring spellcraft. Sidestepping any simple moral for the sake of a more ambiguous, folkloric tale of a radical journey back to where one started, the film is as beguiling and relaxing as it is unnerving.

Despite their lack of relation to one another, the films in Criterion’s box set share certain thematic and stylistic parallels. All four boast stellar vistas, while the magic-realist tone of Kummatty makes for easy programming alongside the almost alien atmosphere of The Fall of Otrar. The more intimate drama of perseverance and struggle seen in Yam Daabo mirrors much of the same motivating hardship besetting the central family of Chronicle of the Years of Fire before that film expands into something much larger.

Image/Sound

All four films receive transfers from new 4K restorations (overseen by the World Cinema Project in collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna), and given the sorry state of preservation that some of these movies were in previously, the results are astounding. The streaks of verdant color in Kummatty and Yam Daabo pop against the swaths of brown and yellow soil and sand. Both the sepia-tinted monochrome and full-color scenes of The Fall of Otrar look crisp with stable contrast and clarity well into the background of deep-focus compositions. Chronicle of the Years of Fire looks best of all, with the image depth so clear that you can make out the sand cakes into the lines of faces and the stained browns and yellows on well-worn desert clothing.

The soundtracks are of more variable quality, all seemingly endemic to the conditions in which they were recorded. (A tinniness can be heard in The Fall of Otrar when characters’ voices echo in cavernous rooms.) Still, there are no discernible issues with the discs’ reproduction of these tracks, and in all cases dialogue, music, and sound effects are well balanced.

Extras

Each of the films comes with an introduction from Martin Scorsese, who recounts his memories of seeing them for the first time and of the World Cinema Project’s often fraught efforts to restore them. A documentary about the making of The Fall of Otrar amid the collapse of the Soviet Union features interviews with director Ardak Amirkulov, actor Tungyshbai Dzhamankulov, production designer Umirzak Shmano, and film journalist Gulnara Abikeyeva, while the other films are supplemented with interviews with film scholars (and, in the case of Kummatty, its filmmaker’s son, Ramu Aravindan). These interviews all provide helpful social context for the times and places in which the movies were made, as well as deeper dives into the oeuvres of their respective filmmakers. An accompanying booklet contains essays on the films by critics and historians Joseph Fahim, Chrystel Oloukoï, Ratik Asokan, and Kent Jones.

Overall

The Criterion Collection offers four neglected classics their much-deserved moment in the sun with the latest iteration of its World Cinema Project series.

Cast: Yorgo Voyagis, Larbi Zekkal, Cheikh Nourredine, Hassan El-Hassani, Leila Shenna, Aoua Guiraud, Moussa Bologo, Ousmane Sawadogo, Fatimata Ouédraogo, Assita Ouédraogo, Ambalappuzha Ramunni, Ashok Unnikrishnan, Sivasankaran, Kothara Gopalkrishnan, Vilasini, Dokhdurbek Kydyraliyev, Tungyshbai Dzhamankulov, Bolot Beyshenaliyev, Abdurashid Makhsudov Director: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Idrissa Ouédraogo,G. Aravindan, Ardak Amirkulov Screenwriter: Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Tewfik Fares, Rachid Boudjedra, Idrissa Ouédraogo,G. Aravindan, Kavalam Narayana Panicker, Ardak Amirkulov, Aleksei German, Svetlana Karmalita, Ardak Amirkulov Distributor: The Criterion Collection Running Time: 502 min Rating: NR Year: 1975 - 1991 Release Date: January 20, 2026 Buy: Video

2025 Avant-Garde Masters Grants to Preserve Seventeen Films

The National Film Preservation Foundation and The Film Foundation are pleased to announce the 2025 Avant-Garde Masters Grants. Works by Heather McAdams, Kathleen Laughlin, and Michael Mideke will be preserved and made accessible with generous funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

The Chicago Film Society will continue its efforts to preserve the work of Chicago-based alternative cartoonist and filmmaker Heather McAdams, with eight titles slated for restoration. Known for her playful use of found footage and recontextualized sound, this selection represents a vibrant cross-section of McAdams’s body of work—highlighting her humor, inventive use of media, and distinctive filmmaking techniques. From early Super 8 student films like The Dream (1978) and Dr. Loomis (1978) to Jay Elvis (1991), an eccentric portrait of an Elvis impersonator, the collection traces the evolution of her style. Films such as The Space Cadets (1979), Joe Was Not So Happy (1990), and Mr. Glenn W. Turner (1990) feature hallmark elements of her practice, including appropriated soundtracks and collage-like visuals. Better Be Careful (1986) showcases her signature use of scratch animation, while My Postcard Collection (1999) stands out for its advanced animation techniques.

he Walker Art Center will preserve Kathleen Laughlin’s Susan Through Corn (1974), a lyrical short that follows the filmmaker’s sister, Susan, through the cornfields of St. Paul, Minnesota, in what Amos Vogel described as “an original vision, of summer, youth, a moment.” With a background in visual arts and animation, Laughlin was an integral part of the Twin Cities’ independent filmmaking community, contributing as both a teacher and graphic designer at Film in the Cities, the region’s landmark media arts center. In 2024, the Walker Art Center received an Avant-Garde Masters grant to preserve Laughlin’s earlier film Opening/Closing (1972).

Eight films by Michael Mideke will be preserved by Anthology Film Archives, marking an overdue rediscovery of a filmmaker once described as “one of the truly unknown geniuses of black-and-white filmmaking.” Though highly regarded by his contemporaries, Mideke’s work disappeared from distribution after he shifted focus away from filmmaking. His films reveal a deep fascination with the texture and physicality of celluloid, as seen in Scratch Dance (1972), a hypnotic composition of hand-scratched black leader layered through fades and superimpositions, and Phi Textures (1975), an exploration of film grain and the "Phi Phenomenon"—the illusion of motion from static images. Mideke frequently incorporated organic materials like plants and leaves, printing them directly onto film in works such as Shadow Game (1964), Twig (1966), and Flight of Shadows (1973), each of which emphasizes the tactile and ephemeral qualities of nature and film alike. Anthology Film Archives is excited to preserve and reintroduce Mideke’s visionary body of work to contemporary audiences.

Now in its twenty-third year, the Avant-Garde Masters program, created by The Film Foundation and the NFPF, has helped 34 organizations save 251 films significant to the development of the avant-garde in America. Funding for the program is generously provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. The grants have preserved works by 92 artists, including Kenneth Anger, Shirley Clarke, Bruce Conner, Joseph Cornell, Oskar Fischinger, Hollis Frampton, Barbara Hammer, Marjorie Keller, George and Mike Kuchar, and Stan VanDerBeek. Click here to learn more about all the films preserved through the Avant-Garde Masters Grants.

63rd New York Film Festival Revivals Announced

Press Release

Film at Lincoln Center announces the Revivals selections for the 63rd New York Film Festival. Expanding the traditional canon, Revivals celebrates works that have been restored, preserved, or digitally remastered. Featuring rediscovered gems and influential rarities, this selection highlights 12 films that have been acclaimed for their artistic innovation and cultural significance or that were underappreciated in their time but offer fresh relevance for today’s audiences.

Presented by Film at Lincoln Center in partnership with Rolex, NYFF63 takes place September 26 through October 13 at Lincoln Center and in venues across the city.

Secure your tickets with Festival Passes, limited quantities on sale now with final discounts through today, August 14. Single tickets go on sale September 18 at noon ET, with pre-sale access for FLC Members and Pass holders.

This year’s Revivals notably boasts two major Indian films of the 1970s: the recently completed director’s cut of Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (1975), the biggest action-adventure film ever made in India, and a glorious restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Days and Nights in the Forest (1970), a fully dimensional portrait of a generation of young Indian men that deserves to be counted among Ray’s crowning achievements.

Making use of new research and recently discovered materials, Queen Kelly (1929) is a sumptuous reconstruction of Erich von Stroheim’s unfinished silent-era epic. The restoration of Mamoru Oshii’s haunting Angel’s Egg (1985) is a major event for anime fans and cinephiles alike (and is one of two Japanese films in this year’s Revivals lineup). Howard Brookner’s documentary Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars (1985) follows the great theater artist Robert Wilson (who died in July at age 83) during his creation of an epic 12-hour opera for the 1984 Summer Olympics. The section also includes T’ang Shushuen’s The Arch (1968), a pioneering work of Hong Kong independent cinema that serves as an overdue reintroduction of a groundbreaking female director.

Several of this year’s Revivals selections are notable for their continued social and political relevance. Yasuzo Masumura’s elegant masterwork The Wife of Seisaku (1965) is a fierce critique of militarism, rigid gender roles, and social norms in prewar Japan. The Razor’s Edge (1985), by Lebanese war correspondent–turned–filmmaker Jocelyne Saab, offers a vivid and arresting portrayal of life during wartime. Flora Gomes’s Mortu Nega (1988), a milestone of African cinema set during the end of Guinea-Bissau’s War of Independence, remains as politically urgent and emotionally resonant now as ever.

Two restorations making their world premiere are a 2K restoration of Mary Stephen’s Ombres de soie (1978), a fascinating early work by a filmmaker who would go on to edit films by Éric Rohmer, among many others, and a 4K restoration of Henry Jaglom’s Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? (1983), a comedic portrait of midlife romance in 1980s New York. Rounding out the selection is another undersung entry in the annals of American independent filmmaking, Ossie Davis’s vital social drama Black Girl (1972).

The Revivals section is programmed by Florence Almozini, Dan Sullivan, and Gina Telaroli in collaboration with Dennis Lim.

NYFF63 Revivals is supported by Anne-Victoire Auriault.

NYFF63 is generously supported by Festival Co-Chairs Susan and John Hess, Almudena and Pablo Legorreta, Imelda and Peter Sobiloff, and Nanna and Dan Stern; Vice Chairs Susannah Gray and John Lyons, and Tara Kelleher and Roy Zuckerberg; and Supporters Hillary Koota Krevlin and Glenn Krevlin, Ronnie Planalp, and Ari Rifkin.

The New York Film Festival is an annual celebration of the most significant films from around the world. Since its inception in 1963, NYFF has played a pivotal role in shaping film culture, presenting a curated selection of bold and remarkable works by acclaimed directors alongside emerging talents.

Secure your tickets with Passes, limited quantities on sale now with final discounts through today, August 14. NYFF63 single tickets will go on sale to the general public on Thursday, September 18 at noon ET, with pre-sale access for FLC Members and Pass holders prior to this date. Become an FLC Member by August 29 to secure NYFF63 pre-sale access and discounted tickets year-round. NYFF63 Press and Industry accreditation is now open through August 18.

Explore the NYFF63 lineup. The Talks section and more will be announced soon. Sign up for NYFF updates for the latest news.

Revivals Films & Descriptions

Angel’s Egg / 天使のたまご

Mamoru Oshii, 1985, Japan, 73m

Japanese with English subtitles

New York Premiere of New 4K Restoration

Angel’s Egg. Courtesy of GKIDS.

Now recognized as a landmark work of animation, Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg is a cryptic, allegorical masterpiece, a hypnotic collage of signs and symbols, enigmatic ideas and overwhelming emotions. Inspired in part by the work of Andrei Tarkovsky and made in collaboration with legendary illustrator Yoshitaka Amano, Angel’s Egg is set in a nameless, ravaged land. A young girl scours the ruins of an abandoned city searching for food, while transporting a large egg she believes contains an angel. She then encounters a young man who wishes to crack the egg open. But the plot is, in a sense, neither here nor there: The central action of Angel’s Egg is Oshii and Amano’s astounding imagery, conjuring the vastest of sci-fi dystopias and provocative biblical motifs. Haunting, curiously intimate, and boldly experimental, Angel’s Egg is perhaps Oshii’s most personal work, and a crucially important film in anime history. A GKIDS release.

4K restoration supervised by Mamoru Oshii. Colorist Noboru Yamaguchi. Mix Supervisor Kazuhiro Wakabayashi. Sound Effects Restoration Kaori Yamada. Digital Restoration Yoko Arai, Kensuke Nakamura, Eiji Yamataka, Tajima Onodera. Presented by Tokuma Shoten Publishing.

The Arch / 董夫人

T’ang Shushuen, 1968, Hong Kong, 95m

Mandarin Chinese with English subtitles

New York Premiere of New 4K Restoration

The Arch. Courtesy of M+.

A pioneering work of Hong Kong cinema, T’ang Shushuen’s self-financed debut feature—produced and released when the broader Chinese film industry was almost completely dominated by men—was among the first independent films to break out and garner international acclaim. Set in 17th-century China, the film follows its titular protagonist (Lisa Lu, who won a Golden Horse Award in 1971 for her performance) as she finds her heart torn between her beloved daughter and the younger man who has awoken her dormant desires. An emotionally magisterial portrait of the plight of women in Chinese society, The Arch is a film of striking visual richness and distinctive rhythms, achieved by T’ang through two notable collaborations: it was shot by Subrata Mitra (best known for his work with Satyajit Ray and Merchant-Ivory), and edited by the great documentarian Les Blank.

The film was restored in 4K by M+, Hong Kong, in 2025, from a 35mm release print preserved at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum, and Pacific Film Archive, and a 35mm release print preserved and scanned at the BFI National Archive. Conformation, restoration, and color grading were undertaken at Silver Salt Restoration.

Black Girl

Ossie Davis, 1972, U.S., 35mm, 97m

New York Premiere of Newly Restored 35mm Print

Black Girl. Courtesy of UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Actor and activist Ossie Davis’s third feature as director, adapted from J. E. Franklin’s popular off-Broadway play, stars Peggy Pettitt as Billie Jean, a misunderstood young Black woman attempting to build a new life by becoming a dancer. Billie Jean lives with her janitor mom, Mama Rosie (Louise Stubbs), along with her older half-sisters, their children, her grandmother, and her grandmother’s boyfriend. The stellar cast, including Claudia McNeil, Brock Peters, and Davis’s wife Ruby Dee, dig deep in every scene, creating a fiercely honest world and a poignant intergenerational portrait that captures the personal effects and rooted realities of poverty. Pettitt, a lifelong teacher working in experimental theater and bringing her skills to prisons, drug treatment centers, homeless shelters, and more, was nominated for Best Actress by the NAACP for this, her one and only screen performance. The textures and colors of this moving social drama are especially vibrant on the newly restored 35mm print, cementing Black Girl’s legacy as a vital and prescient meditation on Black femininity and the ties that bind.

Restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

Can She Bake a Cherry Pie?

Henry Jaglom, 1983, U.S., 91m

World Premiere of New 4K Restoration

Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? Courtesy of Hope Runs High.

New York’s Upper West Side comes to life in actor-director Henry Jaglom’s (A Safe Place, NYFF9) freewheeling fourth feature. Karen Black embodies Zee, a middle-aged woman abandoned by her husband. Wandering the streets of Manhattan and endlessly muttering to herself, she serendipitously meets Eli (Jaglom regular Michael Emil) at a coffee shop. A topsy-turvy romance ensues as they go to concerts and movies, fight and make love, and traverse city streets filled with real-life pedestrians—the filmmakers preferring to capture New York as it is over hiring extras and staging scenes. Frances Fisher and Michael Margotta round out the cast, with notable cameos from Larry David and Jaglom’s friend and business partner Orson Welles, who plays a charming movie magician. An endearing and dryly comedic portrait of the randomness of urban life, Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? is humbly suffused with a sweet and tender spirit, but it’s also a captivating, invaluable document of a time and a place. A Hope Runs High Films release.

This restoration was completed from a 4K, 16-bit scan of the 35mm interpositive by Vinegar Syndrome in Bridgeport, Connecticut, via an ARRISCAN XT. Scanning Technician: Brandon Upson. Frame-by-frame manual digital restoration and color grading was completed by Marcus Johnson of Emulsional Recovery. This restoration was a collaboration between Hope Runs High and Cinématographe, supervised by Taylor Purdee of Hope Runs High and Justin LaLiberty of Cinématographe. Film materials made available through the generous cooperation of the Academy Film Archive.

Days and Nights in the Forest / Aranyer Din Ratri

Satyajit Ray, 1970, India, 116m

Bengali with English subtitles

U.S. Premiere of New 4K Restoration

Days and Nights in the Forest. Courtesy of Janus Films.

Among Satyajit Ray’s crowning achievements—albeit one ripe for reappreciation—Days and Nights in the Forest (NYFF8) is an astonishing, fully dimensional portrait of a generation of young Indian men yearning for a break with the tyranny of everyday life. We follow four bachelor friends as they decamp for a forest holiday in Jharkhand, during which they hope to cut loose and sow wild oats. But when the four cross paths with a local tribe, the dynamics grow ever more complicated—not least between the men themselves. Featuring some of the richest characterizations in Ray’s legendary oeuvre, Days and Nights in the Forest somewhat resembles the contemporaneous films of John Cassavetes, though Ray introduces profound elements of class and gender to the psychodramatic proceedings, arriving at a masterwork that’s entirely his own. A Janus Films release.

Presented and restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project at L’Immagine Ritrovata in collaboration with Film Heritage Foundation, Janus Films, and the Criterion Collection. Funding provided by the Golden Globe Foundation. Special thanks to Wes Anderson. 4K restoration completed using the original camera and sound negative preserved by Purnima Dutta, and magnetic track preserved at the BFI National Archive. Special thanks to Sandip Ray.

Mortu Nega

Flora Gomes, 1988, Guinea-Bissau, 96m

Portuguese with English subtitles

U.S. Premiere of New 4K Restoration

Mortu Nega

Flora Gomes’s debut feature is an enduringly influential work of historical ethnofiction, and for good reason: synthesizing historiography with mythology to striking, vibrant effect, Mortu Nega is a structurally fascinating and texturally engrossing meditation on revolution. We begin toward the end of the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence of the mid-1970s, following Diminga (Bia Gomes), a wounded soldier’s devoted wife, as she heads to battle to be with her husband. The war soon draws to a close, and we then follow Diminga as she struggles to extract support and dignity from a post-revolutionary bureaucratic apparatus. The rare war film that insistently poses the question “what comes next?” this singularly thought-provoking political drama pays tribute to Guinea-Bissau’s struggle for independence while remaining critical of the society to come.

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Flora Gomes. Funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. This restoration is part of the African Film Heritage Project, an initiative created by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers and UNESCO—in collaboration with Cineteca di Bologna—to help locate, restore, and disseminate African cinema.

Ombres de soie (Shades of Silk)

Mary Stephen, 1978, Canada/France, 62m

French and Mandarin Chinese with English and French subtitles

World Premiere of New 2K Restoration

Ombres de soie (Shades of Silk)

An accomplished film editor who went on to forge a long creative partnership with none other than Éric Rohmer, Hong Kong–born Mary Stephen’s 1978 debut feature announced her as a director to watch in her own right. Suffused with alluring atmospherics and a slight air of the oneiric, Ombres de soie traces the relationship between two Chinese women in Shanghai in 1935; through glances, gestures, and confessional voice-overs, the two women negotiate the tension between their shared wish for stability and the nagging sense that there may be more to their bond than meets the eye…. An astounding low-budget achievement (in which 1970s Paris passes for 1930s Shanghai), this entrancing film evokes the Marguerite Duras of India Song, which is no accident: Stephen explicitly wished for Ombres de soie to be a counterpoint to India Song, from an Asian woman’s point of view.

Ombres de soie (Shades of Silk) was restored from a 16mm print scanned at Library and Archives Canada. The 2K restoration work was carried out at L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna in 2024, and is made possible by the generous support of M+, Hong Kong, 2024.

Queen Kelly

Erich von Stroheim, 1929, U.S., 105m

North American Premiere of New 4K Restoration

Queen Kelly. Courtesy of Milestone / Kino Lorber.

A decadent late-silent masterpiece, Erich von Stroheim’s epic unfinished swan song pulls no punches. His characters contend with whippings, suicide, a German East African bordello and more in this story of a prince, the orphan girl he falls in love with, and the mad queen whose jealousy wreaks havoc on everyone involved. The great silent film star Gloria Swanson plays Patricia Kelly, the convent orphan whose life is turned upside down when Prince “Wild” Wolfram (Walter Byron) becomes obsessed with her, angering his betrothed queen. The making of the film was rife with controversy: Swanson’s then-lover Joseph P. Kennedy provided the financing that quickly spiraled out of control, and a fed-up Swanson eventually fired von Stroheim. This vital new digital reconstruction, overseen by Milestone Films’ Dennis Doros, brings von Stroheim’s original script to life, using new research and recently discovered materials. The result is Queen Kelly in its most complete and spectacular form to date, belatedly closing the circle on von Stroheim’s legendary directing career. Featuring a new orchestral score by Eli Denson. A Milestone / Kino Lorber release.

Reconstruction: Dennis Doros and Amy Heller, Milestone Film & Video, Harrington Park, NJ. Nitrate materials and stills courtesy of The George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York. 4K digital stabilization, timing and cleanup by Metropolis Post, NYC. Colorist: Jason Crump. Digital restoration artist: Ian Bostick. Supervised by Milestone Films.

The Razor’s Edge / Ghazl El-Banat

Jocelyne Saab, 1985, France/Lebanon, 102m

Arabic and French with English subtitles

U.S. Premiere of New 4K Restoration

The Razor’s Edge

“I’ve invented places, as if by making a work of fiction about them, I could preserve them,” the Lebanese war correspondent–turned–filmmaker Jocelyne Saab said of her interest in fiction. Her 1985 drama The Razor’s Edge takes place during the Lebanese Civil War and centers on the bond formed between Karim (Jacques Weber), a fortysomething painter, and Samar (Hala Bassam), a teenager who grew up during the war (Juliet Berto has a small but striking role as Karim’s friend). Underneath the character-driven narrative is another story, that of a place. Saab started her career as a journalist working for French television and her reporter’s eye deftly captures the destruction of war-torn Beirut and the disparate but vibrant people wandering through its rubble and ruins. Screenwriter Gérard Brach (The Tenant, Identification of a Woman) worked on the final version of the script, and the result, juxtaposing the creation of art with violence, is an arresting meditation on humanity’s struggle in the face of unthinkable horror.

Restored in 4K in 2025 by Association Jocelyne Saab in collaboration with Cinémathèque suisse and La Cinémathèque québécoise at Cinémathèque suisse and Association Jocelyne Saab laboratories, from the positive preservation copy of the original cut presented at Cannes in 1985. Funding provided by Association Jocelyne Saab and Nessim Ricardou-Saab.

Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars

Howard Brookner, 1985, U.S., 94m

English, German, Italian, and Japanese with English subtitles

North American Premiere of New Restoration

Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars

In the early ’80s, legendary theater artist Robert Wilson (who died in July at the age of 83) set out to create an epic 12-hour opera, a collaboration between six international theater companies, that would take place during the 1984 Summer Olympics. Filmmaker Howard Brookner, Wilson’s good friend, documents the dizzying and difficult process, and traces the history of Wilson’s hypervisual theatrical work, in this fascinating portrait of a deeply dedicated artist working at an incredibly high level. Grounded in the practical derailments—schedules, budgets, exhaustion—that often accompany ambitious artistic undertakings, the film has been long unseen, with some original materials lost to Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Aaron Brookner, the filmmaker’s nephew, has spent 12 years on this invaluable new restoration of a surviving 16mm print, as well as video tapes and magnetic tapes for audio, to finally do justice to Wilson’s artistic process, as well as Brookner’s own gifts for intimate documentation. A Janus Films release.

Restored in 2025 by Pinball London – Janus Films – The Criterion Collection at Pinball London, Bando a parte, Dan Zlotnik, and Matar Studio from a 16mm print, a VHS, and the stereo 16mm optical sound. Funding provided by Howard Brookner Legacy Project, Howard Brookner Estate, Pinball London and Janus Films – The Criterion Collection. Restoration supervised by Aaron Brookner, Paula Vaccaro, and Carlos Morales/EPost.

Sholay (Original Cut)

Ramesh Sippy, 1975, India, 204m

Hindi with English subtitles

U.S. Premiere of New 4K Restoration

Sholay

Conceived as the biggest action-adventure film ever made in India, Ramesh Sippy’s deeply influential 1975 “Curry Western” remains a towering landmark in film history. Written by the legendary screenwriting duo Salim–Javid, the film stars Sanjeev Kumar as a retired cop who, in seeking revenge against a nihilistic dacoit leader (Amjad Khan), enlists the help of two slick, charismatic crooks whom he put behind bars (unforgettably portrayed by Amitabh Bachchan and Dharmendra). Naturally, the criminal duo soon fall in love with two local village girls, but danger remains on the horizon. A delirious four-course meal of action, musical numbers, ultramagnetic performances from Indian cinema’s most iconic actors, and jaw-dropping wide-screen 70mm cinematography, Sholay is here presented in its recently completed director’s cut, the most faithful approximation of Sippy’s original ending before it was censored by the Indian Censor Board.

Restored by Film Heritage Foundation at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with Sippy Films. Funding provided by Sippy Films. Sholay was restored using the best surviving elements: an interpositive and two color reversal intermediates found in a warehouse in the U.K. and a second interpositive dating from 1978 deposited by Sippy Films and preserved by Film Heritage Foundation. The sound was restored using the original sound negative, and the magnetic soundtrack preserved by Film Heritage Foundation. The film was originally shot on 35mm and blown up to 70mm for release. No 70mm prints of the film survive. The original camera negative was severely damaged due to heavy vinegar syndrome with coils adhesion and halos, overcoat deterioration both on base side and emulsion side, and base distortion. This restoration of the film in 4K includes the original ending as well as two deleted scenes and with the original 70mm aspect ratio of 2.2:1.

The Wife of Seisaku / 清作の妻

Yasuzo Masumura, 1965, Japan, 94m

Japanese with English subtitles

North American Premiere of New 4K Restoration

The Wife of Seisaku. © Kadokawa Corporation 1965

Considered a major work within Yasuzo Masumura’s remarkable and underrated filmography, The Wife of Seisaku finds the Japanese auteur again collaborating with his muse, Ayako Wakao (Daiei Studios’ top actress at the time). During the run-up to the Russo-Japanese War, Okane (Wakao), a widow, returns to her home village, only to be ostracized when she falls in love with an intensely idealistic young soldier. When he returns from the front wounded, Okane goes to extreme lengths to ensure that he won’t return to the battlefield. Masumura’s restrained, even minimalistic stylization is an elegant stage upon which Wakao enacts a psychodramatically rich and politically provocative tour de force.

The film was restored in 4K at IMAGICA Entertainment Media Services from the original 35mm negative films. For the sound, a direct print was generated from the 35mm sound negative, and the audio was digitized and restored. In this digital restoration, we aimed to repair the damage to the images and colors caused by the age-related deterioration of the materials, while at the same time restoring all of the texture and beauty that remained in the film at the time of its release. The grading was supervised by Masahiro Miyajima, a former member of Daiei Kyoto Studios’ Cinematography Department, who worked for many years as chief cinematography assistant to Daiei’s legendary cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa and is familiar with Daiei’s look. The method that surprised Martin Scorsese when The Film Foundation restored Ugetsu (1953) was used again this time: storyboards of all the cuts were transcribed, and the director’s and photographer’s aims were analyzed based on the cut divisions and other information.

FILM AT LINCOLN CENTER

Film at Lincoln Center (FLC) is a nonprofit organization that celebrates cinema as an essential art form and fosters a vibrant home for film culture to thrive. FLC presents premier film festivals, retrospectives, new releases, and restorations year-round in state-of-the-art theaters at New York’s Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. FLC offers audiences the opportunity to discover works from established and emerging directors from around the world with a passionate community of film lovers at marquee events including the New York Film Festival and New Directors/New Films.

Founded in 1969, FLC is committed to preserving the excitement of the theatrical experience for all audiences, advancing high-quality film journalism through the publication of Film Comment, cultivating the next generation of film industry professionals through our FLC Academies, and enriching the lives of all who engage with our programs.

Rolex is the Official Partner and Exclusive Timepiece of Film at Lincoln Center.

Support for the New York Film Festival is also generously provided by Official Partner The New York Times; Supporting Partner Netflix; Contributing Partners Kino Film Collection from Kino Lorber Media Group, The Travel Agency: A Cannabis Store, Dolby, BritBox, New York Film Academy, the School of Visual Arts BFA Film, IMDbPro, Epson America, Inc., Manhattan Portage, and Thompson Central Park New York; Media Partners Variety, Deadline, WABC-TV, The Hollywood Reporter, The WNET Group, IndieWire, and The Envelope by the Los Angeles Times. Additional support is provided in part by the NYC’s Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment and the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature. American Airlines is the Official Airline of Film at Lincoln Center.

For more information, visit filmlinc.org and follow @TheNYFF on X and Instagram.

For press inquiries regarding Film at Lincoln Center, please contact:

John Kwiatkowski, Film at Lincoln Center, JKwiatkowski@filmlinc.org

Eva Tooley, Film at Lincoln Center, ETooley@filmlinc.org