Marcel Ophuls says that “The Memory of Justice” is his best movie. This catches your attention, given that another movie he directed, “The Sorrow and the Pity,” might be the best documentary ever made.

“I think it’s the most personal and sincere work I’ve ever done,” he said recently about “The Memory of Justice,” a fourandahalfhour examination of war crimes and guilt from 1976 that focused on the Nuremberg trials and the Vietnam War. “And it disappeared.”

The film’s history is a drama in itself, part thriller, part tragedy. It involves an American Army base, the latenight pilfering of film canisters, a screening that left Mike Nichols in tears and a fatal review. The long final act ends in redemption at the hands of Martin Scorsese (among others) and includes the film’s longdelayed television premiere, on HBO2 on Monday, April 24.

This is the story according to the 89-year- old Mr. Ophuls, anyway, and he tells it — by phone recently from his home in Southern France — very convincingly, with frequent bouts of wheezing laughter.

The son of Max Ophuls, the great German director of romantic melodramas (“La Ronde”), Mr. Ophuls tried fiction filmmaking with mixed results and moved into nonfiction to find work. “It all has to do with groceries,” he said. “Not so much with cinema.”

The need to put groceries on the table eventually resulted in “The Sorrow and the Pity,” the hugely influential 1971 film about collaboration in Vichy France. A few years later Mr. Ophuls learned that 50 hours of raw footage of the Nuremberg trials, shot by the United States Army Signal Corps, were stored at a Maryland base. He gained access and started viewing the reels, which had to be hand-rolled. Every so often he broke the film, irritating his Army minders.

The documentary he made using that footage was wide-ranging and open-ended, not just a history of the trials, though it incorporated that. Tackling the questions of national and individual culpability and guilt, Mr. Ophuls interviewed American conscientious objectors and whistleblowers (like Daniel Ellsberg), French veterans of Algeria and many Germans, from surviving Nuremberg defendants like Albert Speer to college students born after the war. He also put himself in the movie. With his family, and again with his film students at Princeton, he discussed the documentary’s themes and posed questions to his wife, the daughter of a German veteran.

Not all of the producers, a mix of British and German backers, were happy with the results. There were complaints about the film’s length and some brief nudity, Mr. Ophuls said, and requests that more focus be put on Russian actions during World War II and American actions in Vietnam. With the editing nearly complete, an acrimonious meeting at the Ritz bar in London resulted — depending on whose account you believe — in Mr. Ophuls either being fired (his version) or walking away.

Barred from his own project, he retreated to Princeton. But then the plot turned. Two women who had worked on the film with him hid in the restroom of the London editing suite and sneaked away with a blackandwhite work print of his original edit.

It made its way to New York, where supporters — including Hamilton Fish, the future publisher and social activist, then a recent Harvard graduate — screened it for other filmmakers and critics, including Frank Rich and David Denby. Mr. Denby wrote an article about the situation in 1975 for The New York Times. Mr. Nichols sat motionless for eight hours (with reel changes) and then said to Mr. Fish, ‘So what can I do?’”

With endorsements like that, and the financial backing of Paramount, Mr. Fish was able to negotiate Mr. Ophuls’s return and to see that the film was completed the way its director wished. “An injury had been done to something of great cultural and historical significance,” Mr. Fish said in a recent interview. But it had been healed.

“The Memory of Justice” played at the 1976 Cannes and New York film festivals and received good reviews, including raves from Mr. Rich in The New York Post and Vincent Canby in The Times. But Pauline Kael, a champion of “The Sorrow and the Pity” and the most influential film critic of the time, panned the documentary in The New Yorker. “Striving for complexity,” she wrote, “Ophuls extended his inquiry in so many directions he lost his subject.”

“Who else could get the people to see a five-hour documentary?” Mr. Ophuls said. “It folded after six or seven weeks and hasn’t been heard since.”

Mr. Fish, as a producer, saw things differently — he said that for a film of its type, in the days before specialty distributors had taken off, the commercial release was successful, and he discounted the influence of Kael’s review. But he agreed that “The Memory of Justice” faded out of sight after 1976. “It just was too difficult to keep in play,” he said.

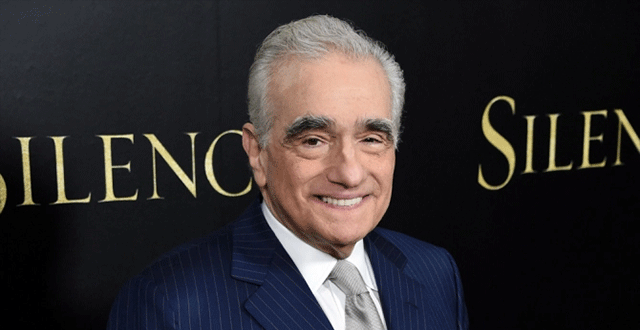

But Mr. Fish never stopped trying. He got grants, including several from Steven Spielberg, to finance efforts over the years to reintroduce the film. Finally he connected with The Film Foundation, the preservation organization whose founders include Mr. Scorsese. It spearheaded a 10-year restoration process that has brought “The Memory of Justice” back from the dead once more.

“Tragically enough, both of the epic 20th-century subjects tackled definitively by Ophuls, Vichy and Nuremberg, remain as pertinent, if not more pertinent, than ever,” said Mr. Rich, a former New York Times columnist who is now a creative consultant at HBO. “The restoration could not be more aptly timed, and I imagine it will come as a revelation to viewers not yet born during its first meager release.”

If enough people see “The Memory of Justice” this time, it might mean that Mr. Ophuls will no longer be known in America largely through Woody Allen’s “Annie Hall,” in which Alvy and Annie stand in line to see “The Sorrow and the Pity.” But if not, Mr. Ophuls won’t be too concerned.

“Oh, I love it,” he said of his indirect contribution to “Annie Hall.” “I think it’s terrifically funny. I know it more or less by heart.” And then he recited several lines of dialogue involving “The Sorrow and the Pity,” correct down to the reference to a Bloomingdale’s charge card.

“I got a letter from Woody Allen thanking me and saying that he would treat the film with great respect etc. etc., which I really didn’t ask for,” Mr. Ophuls recalled. “Who cares if the film is treated with respect? Why should it be?”