Maximilian Schell, Peter Ustinov, Jess Hahn, Melina Mercouri, Robert Morley, and Gilles Ségal in Topkapi (1964)

© Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.

News

‘Film, the Living Record of Our Memory’ Review: How to Save the Movies

Nicolas Rapold

This documentary walks through the delicate task of saving the history of movies with the help of enchanting clips and eagle-eyed preservationists

A canard of the internet age is that more movies are accessible than ever, but “Film, the Living Record of Our Memory” reminds us that our cultural heritage is ever-vanishing and requires constant care just to survive. In this multifarious introduction to motion picture preservation, a crowd of devoted professionals in the field hold up film as not just a vital art form but an essential record of humanity.

Film history is scarred with moments when nobody was minding the store, and when many in the industry were actively burning the store down. Preservationists from across the globe — including rarely represented African, Asian and Latin American archives — here walk through the delicate process of preservation. Obstacles range from epochal shifts (the dumping of silents, the worship of digital), hostile governments (the neglect of Cinemateca Brasileira that led to a fire), and the weather (humidity kills!). Images of rotting reels keep recurring in the film, like a haunting vision.

The film’s director, Inés Toharia, illustrates feats of preservation with lovely clips from obscurities and classics (like “Lawrence of Arabia,” whose sprawling prints were divvied into quarters for restoration by different work groups). Ken Loach, Wim Wenders, Jonas Mekas and Ridley Scott testify, and Martin Scorsese, mastermind of the Film Foundation, is confirmed to be a prince.

Restored by HFPA: "Topkapi" (1964)

Meher Tatna

The poster has a glamorous blonde woman smiling over her bare shoulder, and the caption reads:

“It’s for tonight, darling, in Istanbul . . .

We’ve got a leather vest, a surgeon’s lamp, a suction cup and a Boy Scout knot

Also a mastermind, an electronics genius – and a schmo

Come on – you’re cut in on the theft of the century!”

The film is 1964’s Topkapi, the blonde is Melina Mercouri, the mastermind is her old lover Maximilian Schell, the electronics genius is Peter Morley and the schmo is Peter Ustinov who would win the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his performance, beating out John Gielgud in Becket and Stanley Holloway in My Fair Lady.

In the story, jewel thief Elizabeth Lipp (Mercouri) tracks down her ex-lover Walter Harper (Schell) and entices him into helping her steal the Sultan’s emerald dagger from Istanbul’s Topkapi Museum. The pair decide to hire an amateur crew with no police record as accomplices, and Lipp works her wiles to enlist them. Cedric Page (Morley) is an eccentric British inventor with a sharp wit and a workshop full of dazzling toys, one of which becomes a pivotal prop. Giulio (Gilles Segal, the “human fly”) is a mute athlete who will actually execute the daring robbery. Hans Fischer (Jess Hahn) is a strongman who has to bow out of the caper due to an unfortunate accident, and Arthur Simpson (Ustinov) is the clueless petty hustler they hire to drive a car loaded with weapons over the border into Istanbul.

Arthur manages to get himself caught with the arms at the border by Turkish police, who think he is part of a terrorist gang bent on assassinating foreign dignitaries at an upcoming event. He manages to save himself by promising to spy on his employers, a bargain that is struck when the cops realize the bumbling guy knows nothing. As in all heist movies, nothing goes smoothly. When Hans is injured in a fight, Arthur is recruited to take his place, after he is told of the plan, but also after he has been leaving messages for the Turkish police telling them his colleagues are Russian spies.

The last 40 minutes of the film, when the heist actually takes place, are quite breathtaking, with Walter, Giulio and Arthur scrambling over rooftops to access the museum’s Treasury and trying to cope with Arthur’s fear of heights; Giulio being lowered through a sky window, tethered to a rope controlled by the sweating Arthur, in order to access the dagger; Giulio’s acrobatics suspended on the rope to prevent himself from touching the floor that is wired with alarms; and Elizabeth and Cedric’s ruse to distract a lighthouse man and change the timing of the searchlight that falls on the Treasury’s wall.

Topkapi (1964)

In 1996’s Mission Impossible, director Brian de Palma pay homage to the sequence with a similar scene starring Tom Cruise.

Based on Eric Ambler’s novel “The Light of Day,” Topkapi is directed by Jules Dassin, who moved to Europe when he was blacklisted in the McCarthy witch hunts after being named as a Communist by fellow director Edward Dmytryk. Dassin would marry Mercouri two years after the film’s release: they stayed together until her death in 1994. Mercouri had already starred in several of Dassin’s previous films, including the heist film Rififi in 1955 and the comedy Never on Sunday in 1960. They would work together on eight films. Topkapi was Dassin’s first color film.

The film diverges from the Ambler novel in several ways. The novel’s POV is from the character of Arthur Simpson, and because of that, the reader is unaware of the heist until Simpson learns of it halfway through the story. In the movie, the Mercouri character (whose role is much bigger than that in the novel) informs the audience of the robbery even before the opening credits begin. While Ambler had a hand in the screenplay, sole credit onscreen is given to Monja Danischewsky.

Peter Sellers was originally cast as Simpson, but Ustinov replaced him when Sellers withdrew because, as one account says, he did not get along with Schell. In an ironic twist, Sellers had replaced Ustinov in 1963’s The Pink Panther.

Orson Welles was offered the part of Cedric Page but passed on it. Christopher Plummer and Richard Widmark were in the running for the Walter Harper role. Director Dassin’s son Joseph has a small part as a traveling fair manager who is enlisted to smuggle the dagger out of Istanbul. The younger Dassin would go on to have a stellar career as a singer-songwriter in Europe.

Most of the film was shot in Istanbul, showcasing exotic landmarks like the Topkapi Palace, St. Sophia’s Mosque and the Dolmabahce Palace. Another location was the Kavala harbor in Greece. Interiors were shot at the Boulogne Billancourt Studios in Paris.

For some reason, only the below-the-line crew is listed in the opening credits. The actors’ names appear at the end of the film as they are shown cavorting in an unknown snow-bound location under the caption, “There they go again!” This scene is probably setting up a sequel that ultimately wasn’t to be. There is also a suggestion for another heist in the penultimate scene of the movie. In 1965, a Los Angeles Times article had said Dassin planned a sequel called The Crown Jewels using the same cast, but it was never made.

The film premiered in Paris on September 4, 1964, opening in the US two weeks later. It made $7 million at the box office and was considered a big success. In his New York Times review, critic Bosley Crowther said, “It is another adroitly plotted crime film, played this time for guffaws, and if you don’t split something, either laughing or squirming in suspense, we'll be surprised. We’ll also be surprised if you’re not dazzled by the extravagantly colorful decor and the brilliantly atmospheric setting, which happens to be Istanbul.”

A few years ago, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association asked director Christopher Nolan to choose a film for restoration. His choice was Topkapi, long one of his favorites.

Topkapi was restored at FotoKem Laboratory from the 35mm original camera negative and a 35mm color interpositive. Audio restoration was completed at Audio Mechanics from a 35mm track negative. The photochemical restoration was done by The Film Foundation in collaboration with Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios Inc. Nolan was actively involved in the process. The funding was provided by the HFPA.

Topkapi had its world restoration premiere at the 2022 TCM Classic Film Festival in Hollywood.

Why Do Some Films Get Restored and Others Languish? A MoMA Series Holds Clues

Ben Kenigsberg

History, finances and practical concerns all played a role in preserving the movies being shown at To Save and Project.

A frothy musical comedy from Weimar Germany, starring an actress whose unexpected death at 31 may have been a Gestapo murder. The first known Irish feature to be directed by a woman. An American drama from 1939 distributed to largely Black audiences, starring Louise Beavers as the progressive warden of a reform school.

All these films might have disappeared forever, at least in their complete forms. But all are showing beginning Thursday in To Save and Project, the Museum of Modern Art’s annual series highlighting recent preservation work. Some titles, like the opening-night selection, “The Cat and the Canary,” a popular silent from 1927, were preserved by MoMA itself. Others have been flown in from archives around the globe.

Decisions about which films become candidates for preservation — or even what preservation means for any given movie — are rarely clear-cut. They depend on a combination of commercial interests, historical judgments, economic considerations and the availability and condition of film materials.

Mike Mashon, the head of the moving image section at the Library of Congress, said that when he started at the institution in 1998, there was a common understanding of what preservation meant: making a new film element. That is, a new film copy that could screen in theaters or even a new negative for storage. “The Letter” (1929), an early sound film adapted from a play by W. Somerset Maugham and starring Jeanne Eagels, will screen in the series in a freshly struck 35-millimeter print.

Mashon said there were several reasons for choosing “The Letter” as a project. The library held good original materials, and he expects the film to play well with audiences. “There are plenty of people who really think it’s superior to the Bette Davis 1940 version, and Jeanne Eagels is this great tragic figure in film history,” he said. She died shortly after the picture’s release, and MoMA describes “The Letter” as her only surviving sound movie.

“I Married a Witch” (1942), starring a very funny Veronica Lake as a resurrected witch who first tempts, then falls for, the gubernatorial candidate whose ancestor had her burned at the stake, is even more of a potential crowd-pleaser. Digital technology made it possible to preserve; the restoration was pieced together from several sources that each had its own challenges. The process would have been almost impossible photochemically, said Heather Linville, the supervisor at the Library of Congress’s film preservation laboratory.

Both “The Letter” and “I Married a Witch” received grants from the Film Foundation, the organization started by Martin Scorsese in 1990 to promote the preservation, restoration and exhibition of film. The foundation had a hand in six films showing at To Save and Project, including Luis Buñuel’s “Él” and “The Circus Tent,” a 1978 Indian film that is part of the foundation’s World Cinema Project, whose goal is to preserve movies from countries that have gone underrepresented in film histories.

The foundation’s board members — all filmmakers, including Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Spike Lee and Sofia Coppola — ultimately decide what gets financing, but recommendations are made by archival institutions like the Library of Congress and MoMA, which work with the foundation throughout the year.

She noted that the organizations funding restorations do not have rights to the films. The Film Foundation tries to focus on titles owned by “either individuals or small companies that don’t have the resources to launch a restoration or aren’t paying attention to that because they’re just trying to survive.”

Sometimes repair work is undertaken because the rights holder is interested in a film’s commercial prospects. That was the case with the 1953 science fiction film “Invaders From Mars,” said Scott MacQueen, who supervised the restoration showing at MoMA, and who was until his retirement in 2021 the head of restoration at the UCLA Film & Television Archive.

Moviegoers who attend the MoMA screenings of “Invaders” will notice a much different color palette from that on Tubi, which is showing a version that makes the walls of a police station look violet. That was because of a flaw in the original Super Cinecolor process, MacQueen said, and this update comes closer to the intention of the director, the production designer William Cameron Menzies.

Other times not only are the commercial prospects marginal, but the film itself was barely saved from oblivion. Until now, one of rarest titles in the series would have been “Reform School” (1939), restored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In the film, an advocate (played by Louise Beavers, a star of the 1934 “Imitation of Life”) for more humane treatment of incarcerated boys takes over for a disciplinarian warden and establishes a philosophy of trust, with the hope of preparing the boys to re-enter society and be employed.

While the movie was restored as part of Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971, an exhibition at the Academy Museum, it had been in the academy’s archive since the late 1990s, when Giancarlo Esposito and Laurence Fishburne donated a collection of films distributed by Ted Toddy, a white producer who put out titles with Black casts aimed at Black audiences.

Josef Lindner, the preservation officer at the academy, said it was not clear that there were any surviving film copies of “Reform School” other than the academy’s 16-millimeter print. Still, whether it merited restoration was, for a time, a vexed proposition. Some of Toddy’s movies had a problematic reputation. Many, though not “Reform School,” featured Mantan Moreland, an actor known for broad, minstrel-like caricatures.

Curators helping to plan the “Regeneration” series a few years ago provided the impetus. Seen today, “Reform School” seems ahead of its time in at least some respects, particularly in its depiction of a female warden.

Collaboration among archives is often the key to rediscovery. “Private Secretary,” a 1931 musical comedy from Germany, did not survive in any known, complete 35-millimeter copies. But Stefan Drössler, the head of the Munich Filmmuseum, was able to view a 16-millimeter print at the Library of Congress, which had acquired large quantities of German films after World War II. Two 16-millimeter prints from the library and three reels of a 35-millimeter print form the basis of the new restoration.

“Private Secretary” stars Renate Müller, whose death in 1937 has never been firmly resolved. It may have been a suicide or a murder by the Nazis. (Some sources suggest that Hitler was interested in her, but Drössler said that Müller “loved Georg Deutsch, a Jew who had to emigrate and whom she visited as often as possible.”) She plays a bank typist who does not realize that the man she has fallen for is the bank’s director.

National archives generally have a mission of preserving their countries’ cinematic heritage. But Ireland came to the task late: The country did not have a film repository or a history of preservation until the late 1980s and early ’90s, said Kasandra O’Connell, the head of the IFI Irish Film Archive.

This year, the archive will bring to MoMA a digital restoration of “This Other Eden” (1959), a drama made in the early years of Ardmore Studios, the only studio in Ireland at the time, O’Connell said. The film is also of historic interest in how it dramatizes British-Irish tensions and the legacy of a figure modeled on the Irish revolutionary Michael Collins.

“It’s the first Irish feature we know of that was directed by a woman — even though she was British — Muriel Box,” O’Connell said.

Britain, in a way, saved the film. “We didn’t have our own laboratories in Ireland, so all of the material had to go to the U.K. to be processed,” O’Connell said. Because of that, a lot of negatives ended up in British archives. “If they hadn’t, they probably wouldn’t exist,” she added.

For the Thai Film Archive, MoMA’s showings of “The Adulterer” (1972), a languid thriller about a hermit fisherman, a woman who washes ashore and a man from her past, are a chance to introduce a classic of Thai cinema to New York audiences. Chalida Uabumrungjit, director of the archive, said the filmmaker, Somboonsuk Niyomsiri (directing under the pseudonym Piak Poster), is relatively unknown even to audiences in Thailand, even though the film is on the country’s equivalent of the National Film Registry.

She also noted that the Thai archive sometimes provides support for neighboring countries, like Myanmar, that do not have archives of their own.

Lindner, from the Academy, summed up one of the problems of preservation a different way. “There are so many films that are lost that we know are lost,” he said. “But then there’s the things that we don’t even know that we should be looking for.”

To Save and Project runs Jan. 12 through Feb. 2 at the Museum of Modern Art. Go to moma.org for more information.

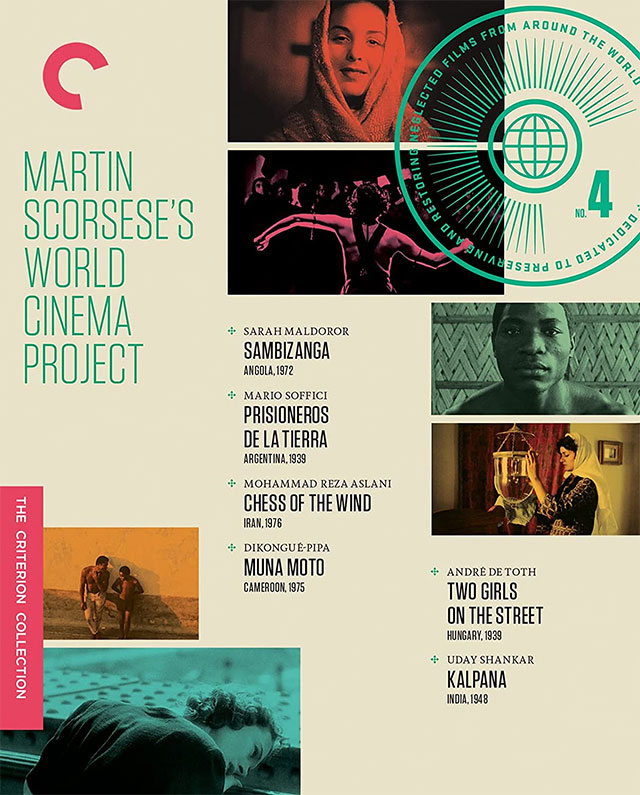

Blu-ray Review: Criterion Shepherds MARTIN SCORSESE'S WORLD CINEMA PROJECT NO. 4

Jim Tudor

Scorsese’s Film Foundation once again teams with Criterion for another round of newly restored films of global significance.

Though the often cinematically verbose Martin Scorsese has far less to say on his video introductions for the half-dozen films packaged together for this fourth edition of his “World Cinema Project,” the selected titles, as always, remain noteworthy.

Several are even vital. Released as a sturdy box set from Criterion to visually match the company’s previous three (and continuing to carry on as the last bastion of Criterion’s long ago abandoned dual-format packaging, including DVDs and Blu-rays of all the content), Scorsese’s Film Foundation has once again heroically gone forth and saved six historically prominent global titles from the ravages of poverty and/or neglect.

At least one director familiar to classic Hollywood film buffs makes the cut this time, as well as a female filmmaker, something particularly rare amid the often very limited filmmaking opportunities in undeveloped countries. Curiously, this WCP batch hails almost entirely from either the mid-to-early 1970s, or the very specific (and cinematically celebrated) year of 1939. The roundup for Volume Four breaks down thusly:

Sambizanga (Angola, Sarah Maldoror, 1972)

Prisioneros de la tierra (Argentina, Mario Soffici, 1939)

Chess of the Wind (Iran, Mohammad Reza Aslani, 1976)

Muna moto (Cameroon, Dikongué-Pipa, 1975)

Two Girls on the Street (Hungary, André de Toth, 1939)

Kalpana (India, Uday Shankar, 1948).

Below, we take more detailed looks at each of the films, as presented…

Sambizanga

Bereft with traumatic anguish over her disappeared husband, Maria (Elisa Andrade) collapses in the home of her trusted confidants. Immediately, one of the women takes her baby boy off her back and swift ushers him onto her breast.

The oppressed people of Angola (at the hands of Portuguese rule) may not have much, but they do have each other within their exceptionally tight knit community. Like any good community, it’s worth fighting for. In the case of Sambizanga, it is named after the area in Luanda where the real revolution began.

That fight broke out in 1961, spurred on by the kind of inhumane treatment witnessed in Sambizanga (1972), which took place just prior to that. In lieu of an organized rebellion (or as it’s referred to by the characters in hushed tones, “The Movement”), Maria is left to desperately scurry around asking about “her man.”

Despite the misleading current descriptions of Sambizanga on sites like IMDb and Wikipedia, the film is not about an imprisoned man valiantly resisting interrogation. That’s part of it, but truly, Sambizanga is a strong woman’s story… as only a strong woman could tell.

The late filmmaker Sarah Maldoror of Sambizanga is regarded and remembered today as one of Africa’s first women to direct a feature film. Her well-travelled life would take her to France and Russia and to the post of assistant director to director Gillo Pontecorvo on his revolutionary potent classic, The Battle of Algiers (1966).

Maldoror would know a thing or two about revolution and would harbor the attitudes to match. But, according to her daughter and not attested to by Sambizanga and her other films, it was poetry, not battle, that defined Maldoror’s artistic soul.

This and many other rare facts are gathered into Criterion’s bonus featurette, On Sambizanga: The Passion and Poetry of Sarah Maldoror (26:00). On it, the filmmaker’s daughter, Annouchka de Andrade, in English, details her mother’s colorful life, career, and philosophies. The featurette also contains subtitled interview footage with Maldoror from 2008.

Maldoror shoots Sambizanga with a universal urgency in a deeply localized Angolan village milieu. (Much of the cast is comprised of non-actors involved with African anti-colonial movements). Filmed in the comparatively less volatile land next door, the People’s Republic of Congo, Sambizanga is written by her husband Mário Coelho Pinto de Andrade, adapted from José Luandino Vieira’s novella.

There’s a powerful scrappiness about the film, heightened by the bright rigidity of the color palette that is all the more impressive thanks to this restoration by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and Cineteca di Bologna at L’Image Retrouvée in association with Éditions René Chateau and the family of Sarah Maldoror.

Prisioneros de la tierra

The opening crawl reads, “Misiones is a breathtaking region in the far north of Argentina with magical charm, endless jungles and deep rivers. There the call to peace and work resounds ever more loudly, but it wasn’t always so… Many years ago men marked by destiny trod the crisscrossing trails of red death blazed by machete in the very heart of the jungle, in a saga of blood and alcohol. Our story takes us back to those strange and turbulent times.”

In a most remote location of Posadas during the troubled time of 1915, workers not only struggled to get by, they literally often struggled to stay alive. Director Mario Soffici’s heavily restored 1939 Argentine classic Prisioneros de la tierra (Prisoners of the Land) forecasts John Huston’s The Treasure of the Sierra Madre insofar as it begins with something of a Western spirit before shifting to something very different.

Although in this case, the shift is felt much sooner, as the exploitation of the many uneducated working class characters, or Mensú, becomes quickly apparent. (Clouzot’s The Wages of Fear comes to mind).

Although the central ideological clash between a particular targeted outspoken oppressed worker (Angel Magaña) and unrelenting boss (Francisco Petrone) plays out in Prisioneros de la tierra as it does in many other social justice-minded movies, right down to shared affection for a woman (Elisa Galvé) heightening and representing the conflict, Soffici goes about it differently. At numerous turns, established sympathies are subverted by simple human nature of the characters.

Soffici’s master stroke may just be in the moment when the repulsively suave villain is receiving comeuppance. For just a few moments during his prolonged torture and degradation, we catch ourselves feeling sorry for him. Or is it simply lament for the release of pent up “Dark Side energy” that our hero is suddenly giving off?

The jungle and its heat make everyone sick and crazy. The sad camp doctor, perpetually drunk on cashaça, may wish to be equated with his impressively unbreakable cane, but is increasingly consumed by his failures. He proclaims that in this terrible place, death is the same as life. Yet, he has no idea just how bad it can get…

A towering, humanist achievement in the history of Argentine cinema, Prisioneros de la tierra has been painstakingly restored to its original 1939 luster and running time. On the short featurette on the process, which was shepherded by Argentine film historians Paula Félix-Didier and Andrés Levinson, the pair discuss just how weathered, worn, and incomplete the film has been until their work was completed in 2019.

For many decades prior, there simply was no viably complete version of Prisioneros de la tierra (“Prisoners of the Earth”, or “Prisoners of the Land”). We are tremendously fortunate to now have this stirring, entertaining, and impactful film readily available and looking pretty remarkable.

Chess of the Wind

Looking more Visconti than Kiarostami with moments resonating as more Lynch than Panahi, director Mohammad Reza Aslani shatters a great many common perceptions of what Iranian cinema is/was. Chess of the Wind (aka, The Chess Game of the Wind; Shatranj-e Baad) came out in 1976 only to disappear amid fervor of its political controversy and predictable courting of certain outrage. Once the Iranian Revolution occurred in 1979, Chess of the Wind was written off as officially gone.

After its negative was discovered in an antique shop in 2015 and the subsequent restoration resurfacing to triumphant acclaim in 2020, however, it’s found its way into Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project No. 4. Thanks to the generous funding of the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, this, as well as most if not all the other endangered films in WCP4, is now back to its intended glory.

Inspired by filmmaker Max Ophüls in general and Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon in spirit, this first of only two narrative features made by documentarian Aslani exudes his trademark ornate visual lavishness throughout. Housebound in an impressively ornate old-world mansion, Chess of the Wind becomes a distinctly sharp, shattering portrait of a family heading towards a violent reckoning.

It’s the turbulent 1920s, as the slipping feudal system is giving way to modernity. The familial power struggle that erupts within this particular home, depicted often with limited, stylized color and a baroque kind of detachment from the type of tactile reality/realism so commonly associated with Iranian cinema, is analogous to broader Iran not only then but at the time of the film’s would-be release.

Chess of the Wind lands the single longest supplemental feature for any film in WCP4. Mohammad Reza Aslani’s daughter Gita Aslani Shahrestani’s fifty-one-minute documentary The Majnoun and the Wind (2022) is a heartfelt if rudimentary investigation into the history of her father’s cloistered masterpiece, and its very recent resurrection.

Aslani, still a sharp and communicative old man at the time of this filming (and this writing), is prominently featured, recalling the 1970s blow-by-blow systemic takedown of Chess of the Wind, as well as his initial skepticism at the notion of its restoration. Made at least in part during the COVID-19 lockdown era, several of the interviews, including members of the film’s cast and crew, and others, are conducted online.

Film critic and festival programmer Hossein Eidizadeh wrote that Chess of the Wind is “truly the Holy Grail of Iranian cinephiles – and a mesmerizing one.” All things considered, it’s pretty amazing how well this film now looks and sounds. (The jazzy, transfixing score by the prolific Sheida Gharachedaghi comes through exceptionally well). With nary a hair pinned dirt road nor village rubble in sight, Aslani’s recovered contemporary classic dares to buck the political and moral strictures of Iran.

Though not explicitly acted upon, Chess of the Wind also exhibits surprisingly sexual currents, particularly in its meticulously restored final portion, which is made to play like a tinted nightmarish silent film from the early, uncertain days of cinema. In both its meta story and its story proper, Aslani’s film serves as a potent, sometimes terse, warning about the tragedies and senselessness of domineering oppression.

Muna moto

Ngando’s uncle is on the make. His four wives aren’t providing the all-important offspring that they’re cultural tradition demands. “Witches,” he calls them. But this is no supernaturally tinged movie. Nor is it the “delicate love story” or “the African Romeo and Juliet,” as some refer to it.

No, Muna moto (The Child of Another) is a nuanced tale of a clash of values between Ngando (David Endene) and his uncle Mbongo (Abia Moukoko) in contemporary (1976) Douala, Cameroon. That, it not so coincidentally happens, is also the hometown of the director, Jean-Pierre Dikongué Pipa.

Douala, as portrayed here in soft greyscale, is a strained village that can’t or won’t navigate its way into the modern world. Dikongué Pipa very obviously has deep issues with this, seeing how he (in a foul mood) couldn’t not make this movie.

The question of “to what degree do we allow tradition and ritual to govern our lives as the world moves forward?” is one that’s been kicked around the world over. (Look no further than Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Flower Drum Song for a wildly different styled exploration). Here though, it feels raw. It feels personal.

Ngando and Ndomé (Arlette Din Bell) are in love. He is young and strapping, his spirit not yet overtaken by scars as his body is on its way to being. She is sensual, outgoing, and, most importantly to those looking to maximize her perceived “value” as a bride, she is a virgin. Because of this, Ngando cannot afford the payment that is traditionally made to her family.

Meanwhile, Ngando’s uncle has inherited all the wealth of our protagonist’s deceased father. The injustice that enables Ngando’s uncle to actively work against him broils just beneath the surface, barely contained. Dikongué Pipa himself, in a new video featurette (by filmmaker Mohamed Challouf and also featuring African film historian Férid Boughedir), explains that this anger was indeed his own. And yet, he’s claimed that maybe only one-fifth of what he truly felt is conveyed in the film.

The faces all throughout Muna moto are some of the most expressive one could ever encounter. This adds to be film’s semi-baroque sensibility, it’s nonlinear narrative freely disjointed, opening with what is a much later sequence.

Even the English subtitling sometimes feels like it’s operating to the beat of a different drum, as sometimes swaths of dialogue go untranslated, and other times, we get a single line that seems more descriptive. But for the most part, the subtitles operate as usual. Inspired by the lofty likes of Buñuel and Bergman, perhaps it’s no surprise that Dikongué Pipa forged his otherwise real-world-based filmmaking aesthetic in the strikingly personal manner of untethered dreaming.

Two Girls on the Street

Amid the bluster and din of life in bustling urban Budapest, there lingers moments of fleeting tenderness throughout director André de Toth’s Two Girls on the Street (Két lány az utcán). For that, thank terrific casting, particularly of the title girls, Bella Bordy as the youthful and naïve Vica Torma and Mária Tasnádi Fekete as the older refined runaway Gyöngyi Kártély.

Adapted from a play by Tamás Emöd and Rezsö Török, this 1939 social realist drama stands as a fine if not at all masterful glimpse of the talent fermenting in the director’s chair. De Toth would go on to have a long, remarkable career helming many a fondly remembered crime (1953’s Crime Wave), Noir (1948’s Pitfall), and Western films (1950’s excellent The Gunfighter; 1959’s psychological Western Day of the Outlaw), as well as the title that Scorsese calls the best 3-D movie ever made, 1953’s House of Wax.

One of only five early features that de Toth would make in his native Hungary, Two Girls on the Street resides in the “just fine” but not at all “great” category. Perhaps its most outwardly distinct calling card is its heavy use of location photography, serving up a vivid look at the Thirteenth District of Budapest.

The 2K digital restoration of the film wonderfully captures that certain dreamy haze of such silver-tinged monochromatic movies of the time. This alluring aesthetic both compliments and contrasts the shifting plights of Gyöngyi and Vica as they navigate their way from disparate poverty to luxury. All the while, they must bob, weave, and second-guess lecherous come-ons, gentlemanly courting, and their own amorphous bond, sometimes resembling a mother/daughter relationship, other times as competitors for certain male affection, and other times leaning towards lovers.

Besides the standard introduction by Scorsese, the title’s supplements include eleven minutes of footage of an elderly de Toth giving an inspirational talk to a very receptive audience. “You don’t direct the films,” he tells them. “The characters direct the films. Each has their own rhythms.” By that rationale, the director indeed directs, insofar as s/he must be attuned to those rhythms.

With the energetically charged and almost anthological Two Girls on the Street, de Toth demonstrates this skill even as he tilts wildly close towards Hollywood melodrama. Fortunately, that’s never a bad thing, although it does tend to fly in the face of the ascribed “social realism” component of the film.

Scorsese refers to de Toth as a “director’s director,” this being early evidence of his brisk and sometimes bold storytelling talent. The social commentary component, however, either takes a backseat or emerges periodically on the business end of a messaging sledgehammer. Still, for all it adds up to, Two Girls on the Street serves as somewhat of a reprieve from the ardently political bellringing that otherwise tend to fuel World Cinema Projectentries.

Kalpana

“God, what’s happened?”, shouts a woman in the final minutes of Uday Shankar’s dance-driven Kalpana. Honestly, I couldn’t begin to tell you.

The newly produced twenty-three-minute Criterion featurette, “On Kalpana”, offers some clarification, thanks to Indian film historians Kamar Shahani and Suresh Chabria. They point out how a key sequence of browbeaten factory workers plays like something out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis or Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times. And, they’re not at all wrong.

Those films make points of propping up their auteurs and their large, uncompromising auteurist visions via demonstrating the deadening factory life of the proletariat. The odd, weird, dark thumping surge that is Kalpana, while not on the level of prime Lang or Chaplin, nonetheless delivers spectacle to pronounced humanist ends.

The opening text scroll of this film invites us to join the filmmaker’s pursuit to make India great again. Those aren’t the exact words, but all those words are there. So immediately, Shankar’s Kalpana might unintentionally strike western viewers as something more twisted than what it is.

But then again, Kalpana, being a thoroughly odd, pulsating, warped journey of monochromatic dance fantasy, is plenty distorted on its own without sounding a dog whistle for fed-up toxic nationalists. Uday Shankar (musician Ravi Shankar’s brother, starring alongside his wife, Amala Shankar, in their only feature film outing) seems quite genuine in his own stated intentions of his homeland’s betterment.

This dreamlike panoply of performance and passion is a feverish experience that’s not like the other movies. As in, any other movies. Although the plot reflects Shankar’s own true-life quest to open a cultural arts center in India, many of the strangely stagey and oddly ornate dance sequences that make up the film are rooted in Hindi mythology.

The prominently featured Shankars themselves dance like nobody’s business, although their bizarrely contorted facial expressions prove inadvertently distracting. Many dancers seem to harbor two expressions, “needing to go to the bathroom” and “going to the bathroom.” As for our main protagonist, if he is going to be a great dancer, he must learn of Taal, the rhythm of the universe. So that’s part of this, too.

Clocking in around two and a half hours, Kalpana proves to be at once entrancing and a bit interminable. The routines are sometimes characters’ dreams, and sometimes simply the narrative mode of integrated dance that occurs in most musicals.

Restored in 2012 from existing film elements from the National Film Archive of India, Kalpana’s black and white cinematography has a dreamy kind of smudginess about it. It resembles nothing else, particularly when it frequently lapses into old world costumed dance numbers. The near-constant drumming, though, becomes lulling. Caffeinate accordingly.

*****

While World Cinema Project No. 4 stands as another fully commendable and impressive effort of otherwise unlikely film preservation -- some of the titles, such as Kalpana and Chess of the Wind, were frighteningly close to becoming lost forever -- the actual boots-on-the-ground review effort of getting through all six of these titles as a collection proved more difficult than the previous box sets. At times, I was utterly defeated by the process. It’s impossible for me to know why that is. I can say, however, that the burden lie entirely on me, and the experience simply wasn’t taking like it had in the past.

None of that is to besmirch the solidity and vitality of these individual titles, nor their filmmakers or appreciators. World Cinema Project No. 4, for all the important effort and resources that went into it as well as the disparate batch of films themselves, is a recommended purchase.

Rushing through it, however, might not be the way to proper experience it. This is more of an aged wine, recovered from the forgotten corners of the world, and uncorked to be appreciated over time.

*****

The official Criterion Collection list of supplements, set features, and points of interest for Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project 4:

DUAL-FORMAT BLU-RAY AND DVD SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES

• New 4K digital restorations of Sambizanga, Prisioneros de la tierra, Chess of the Wind, and Muna moto, and 2K digital restorations of Two Girls on the Street and Kalpana, all overseen by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project in collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna, with uncompressed monaural soundtracks on the Blu-rays

• New introductions to the films by World Cinema Project founder Martin Scorsese

• New and archival interviews featuring Indian film historian Suresh Chabria and filmmaker Kumar Shahani (on Kalpana); Argentine film historians Paula Félix-Didier and Andrés Levinson (on Prisioneros de la tierra); Two Girls on the Street director André de Toth; and Sambizanga director Sarah Maldoror and Annouchka de Andrade, Maldoror’s daughter

• New program by filmmaker Mohamed Challouf featuring interviews with Muna moto director Dikongué-Pipa and African film historian Férid Boughedir

• The Majnoun and the Wind (2022), a documentary by Gita Aslani Shahrestani, daughter of Chess of the Wind director Mohammad Reza Aslani, featuring Aslani, members of the film’s cast and crew, and others

• New and updated English subtitle translations

• PLUS: A foreword and essays on the films by critics and scholars Yasmina Price, Matthew Karush, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Aboubakar Sanogo, Chris Fujiwara, and Shai Heredia