News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

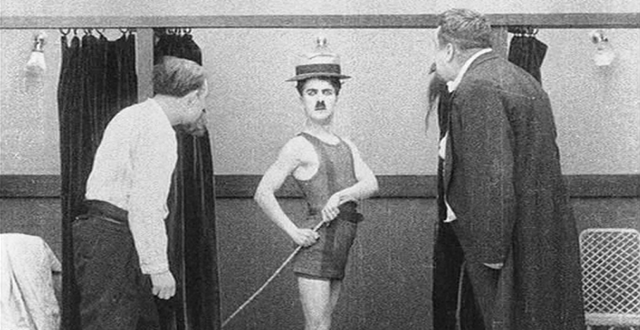

On a couple of occasions, The Film Foundation has facilitated or participated in two restorations of the same film, the first photochemical and the second digital. For instance, Chaplin’s The Cure and Lubitsch’s Forbidden Paradise, both of which were restored on the first round by MoMA. The digital restoration of The Cure was carried out by the Cineteca di Bologna and L’Immagine Ritrovata, with support from the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation and the Material World Foundation, as part of their massive ongoing Chaplin Project. According to David Shepherd, they gathered sources from all over the world and scanned the best elements for every shot, which they then cleaned and stabilized. Damaged frames or passages were inserted from alternate sources when necessary, the contrast and brightness levels were balanced, the frame rate was corrected and the original title cards were recreated. The careful restoration of any silent film, at this moment in the relatively short history of film restoration, involves something like this process. It also involves making choices. “Each film was shot with two different negatives,” explained Shepherd in a Flicker Alley interview, “with two different cameras: the A negative and B negative. The A negative is clearly the better one. You can tell by little things that Chaplin does that are more clever and detailed in one than the other. We tried to restore to the A negative wherever we could, but if a shot was too damaged to restore, we put in footage from the B negative. If there was more material in the B negative that was because they edited it out in the A original.”

The digital work on Forbidden Paradise, also done at MoMA with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, involved a mixture of detective work, interpretation and creativity that, according to Dave Kehr, restored about 90% of the film’s coherence (two missing scenes were summarized by added intertitles). Anyone who remembers excitedly renting a VHS copy of a rare silent film only to go home to find a nonsensical and arrhythmic assemblage of ragged jump cuts will know what I’m talking about. I vividly remember renting a copy of Murnau’s The Haunted Castle, throwing it in the machine and almost instantaneously crash-landing in a state of absolute bewilderment. Mercifully, that film has been restored as well (another act of reconstruction, in this case by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung, working from a nitrate negative and positive).

We know that preservation is an ongoing process, and that we must now constantly migrate preserved elements from one storage medium and/or system to another (bearing in mind that nothing has been proven to last longer than film). But restoration is also ongoing. There will always be new tools, offering increased flexibility and precision…and, inevitably, increased opportunities for choices made in the name of “enhancement” or “improvement” that are often, in the end, creative alterations or outright violations. The plethora of early moving images that have been stabilized and “up-resed” to 4K and 60fps (including films by the Lumière Brothers) is startling to behold, but they raise troubling questions about what images are and the wildly varying levels of respect with which they’re treated.

Going forward, every film will be passed from hand to hand into the future. We have to make sure that there is always love, reverence and humility in the handling.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

THE CURE (1917, d. Charlie Chaplin)

Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art with funding provided by The Film Foundation.

Restored Cineteca di Bologna at L'Immagine Ritrovata, in collaboration with Lobster Films and Film Preservation Associates. Restoration funding provided by The Film Foundation, the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation and the Material World Foundation.

FORBIDDEN PARADISE (1924, d. Ernst Lubitsch)

Preserved by The Museum of Modern Art with funding provided by The Film Foundation and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

Restored by The Museum of Modern Art and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

What exactly do we mean when we say “film culture?” In the broadest sense, it means the community of people across the globe who share a love for the art of cinema. That includes filmmakers, programmers, preservationists, critics, academics, self-described cinephiles and plain old movie fans. Some of us are all of the above put together. For many years, beginning with the introduction of the videocassette, we shared hard-to-find titles through the mail (illegally!), made from the best available sources and possibly upgraded as we went along. This was long before everyone’s eyes were primed for digital sharpness. We were all used to 16mm prints “chained” for television or screened in repertory houses, some of them several thousand light years away from an original or even a dupe negative. Thousands of titles were acquired by companies like Sinister Cinema, which specialized in horror and science fiction and had a good level of quality control. There were also many other fly-by-night companies whose packaging was created with Xerox machines and whose cassettes turned up in abundance at Kim’s Video here in New York. I remember the excitement I experienced when I first saw those titles on the shelves (sorted by filmmaker—the Godard section was labeled “God”). Rossellini’s historical films! Early Mizoguchi!! Straub/Huillet!!! There was the excitement, and then there was the reality of the actual transfer, which was often comically deficient. You would have to squint, very hard, to make out the movement of actors in the frame or to decide whether the dark blur on the left was a tree or a skyscraper. You would find a way to allow for the slurring and warping of imperfect transfers made from imperfect transfers made from ancient broadcasts that had been recorded way back when by someone with a ¾-inch Helioscan deck. As unwatchable as the image often was, the sound was usually worse, a succession of distorted wow-ing utterances and music cues heard through a thickly layered wall of static. At a certain inevitable point, the tracking would fall apart and that would be the end of the “screening.” The homemade tapes that we shared were often just as imperfect. However, it was the sharing that counted.

Edward Yang’s epic film A Brighter Summer Day was one of the titles that floated in the cinephilic ether. Prints were rare. The video copies that circulated were far more acceptable than the extreme cases that I’ve described above, but the version that was most readily available was shortened. Like many of Edward’s films, it remained difficult to see in anything approaching proper conditions for many years, before and after his death.

When I came aboard at the World Cinema Project, the first round of restoration on the film had just been completed by L’Immagine Ritrovata and the Cineteca di Bologna (the WCP later restored Taipei Story). It’s always a great experience to see a film that has been routinely shown under imperfect conditions, carefully restored to something approaching its original state. In this case, it was in Cannes, albeit in the very strangely configured Salle Buñuel (which is wider than it is deep, which means that half the audience has to watch the film from a distorted perspective), in the presence of Edward’s widow Kaili Peng and his son Sean. To see A Brighter Summer Day unfolding on a big screen was startling. It was also, in some way, an affirmation of all those years of sharing imperfect VHS tapes (illegally!), keeping the flame of love for cinema stoked and burning.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

A BRIGHTER SUMMER DAY (1991, d. Edward Yang)

Restored in 2009 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, the Central Motion Picture Corporation, and the Edward Yang Estate. Scan performed at Digimax laboratories in Taipei. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

TAIPEI STORY (1985, d. Edward Yang)

Restored by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project at Cineteca di Bologna/L’immagine Ritrovata laboratory in association with the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique and Hou Hsiao-hsien.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

1:20PM, January 20, 2021

The 1951 film Journey into Light was independently produced by Joseph Bernhard, who had run the Cinecolor Corporation and United States Pictures, a production division at Warner Brothers, with Milton Sperling. Before his death in 1954, Bernhard was involved in some interesting films, including Cloak and Dagger by Fritz Lang and Japanese War Bride and Ruby Gentry, both directed by King Vidor. Journey into Light, the story of a minister from a small New York town (Sterling Hayden) who hits rock bottom after his wife commits suicide and finds redemption at a mission in Los Angeles, was largely shot on actual locations on Skid Row. Weegee was hired as a technical consultant—according to an item about the production in The Hollywood Reporter, he had “recently made an 11-state tour of skid rows and strip joints.” The film, which was photochemically restored by UCLA, is a spiritual melodrama that plays out in raw reality. Ongoing reality also intruded on the production, which had to shut down when Hayden flew to Washington to appear before HUAC as a friendly witness, an act that haunted him to the end of his days.

I will admit that I chose the film to write about today because of its title.

It is very common to be blasé and hopeless about politics in America. Even now. But no one who has lived through the last four years can honestly say that this day doesn’t represent a sea change. Maybe some people took the inauguration ceremony a couple of hours ago for granted. Speaking for myself, the demonstration of comity, humility and good will moved me to tears. And to see it happening at the Capitol, which was stormed, ransacked, desecrated and turned into a battlefield only two weeks ago today, was overwhelming.

A journey into light.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

JOURNEY INTO LIGHT (1951, d. Stuart Heisler)

Restored by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Restoration funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and The Film Foundation.

Out of the Vaults: “Abraham Lincoln”, 1930

Meher Tatna

By the 1920’s, director D.W. Griffith’s star was fading. His controversial but successful The Birth of a Nation was behind him and his later movies barely broke even at the box office, his cost overruns a regular feature of his filmmaking. But he pressed ahead to make his first talkie for United Artists, Abraham Lincoln in 1930, with a production budget of $1 million. It would be his penultimate movie, the film sold as “the biggest undertaking yet launched in talking pictures.” Griffith would say to the Pittsburgh Press of August 31, 1930 that “Abraham Lincoln, to my mind, is the finest thing I have ever done.” His title card on the film reads – ‘Personally directed by D.W. Griffith.’

Lincoln had been a character in The Birth of a Nation, and Griffith decided to devote a whole movie to him inspired by a 1926 biography by poet Carl Sandburg. The script was written by Stephen Vincent Benet, the Pulitzer Prize-winner in 1929 for his poem “John Brown’s Body.”

Griffith’s father had been a Confederate Army colonel in the Civil War, and Griffith was firmly on the Confederate side, sympathetic to the Ku Klux Klan as demonstrated in Birth. In a filmed interview with Walter Huston (who plays the title role in Abraham Lincoln) shown as a prologue to the reissue of Birth in 1930, Griffith talks about his Southern sympathies. “I suppose it began when I was a child. I used to get under the table and listen to my father and his friends talk about the battles they’d been through and their struggles. Those things impress you deeply. And I suppose that got into Birth. Huston then asks him, “Do you feel as though it were true?” His answer is “Yes, I feel so ... That’s natural enough, you know. When you’ve heard your father tell about fighting, day after day, night after night. And have nothing to eat but parched corn. And about your mother staying up night after night, sewing robes for the Klan. The Klan at that time was needed. It served a purpose.”

But in Abraham Lincoln, Griffith switches sides and portrays Lincoln as a hero. The film spans his entire life from birth to death, and the script takes pains to show Lincoln as a human being: a man in love, his depression at the death of his girlfriend, his humor and sense of camaraderie with his fellows, a devoted father and patient husband, and a steadfast commander-in-chief, determined to hold the Union together no matter the current cost if it meant a united country for future generations.

The film is episodic and shows vignettes from Lincoln’s life interspersed with a few battle scenes. It opens with a prologue on a slave ship (missing in some versions) in which the deplorable conditions of slaves below decks are shown, and one dead slave is tossed overboard. Then it goes on to Lincoln’s birth in the famous log cabin, shows him working at his rail-splitting job that supports his law studies, his love affair with Ann Rutledge who dies before they can marry and his subsequent depression, and his courtship of Mary Todd. Then we see him lamenting his failure to accomplish anything at age 50 to the partner of his law practice; his subsequent run for president; going head to head with Stephen A. Douglas, the Democratic nominee, and winning the presidency; the appointment of Ulysses S. Grant to lead the Civil War and the dispatches he receives about its progress in the White House; the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation; his reelection that is mentioned in one scene; then his assassination by John Wilkes Booth in a scene recreated at the Ford’s Theater, similar to the one he filmed for Birth.

Huston, as mentioned before, plays Lincoln, with lifts in his shoes to replicate Lincoln’s height. The nuances of being on camera with audio for the first time were lost on the director and his stars – the declamatory acting style of the theater is maintained throughout the movie, stagy and awkward with long pauses between dialogue. One line – “the Union must be preserved” – is pronounced weightily at least ten times. In one scene, he wanders around the White House in bathrobe and socks, worrying about the war, still declaiming to Mary when she asks him to go to bed.

The script does no one any favors with lines like “Yes, Abe, you’ve got your gingerbread,” which is Ann’s response to Lincoln’s proposal. Una Merkel, a respected stage actress doing her first talkie (and who would go on to a very good career), is Ann Rutledge, and comes across as simpering and coy, her intimate scenes with Huston cringeworthy. The unfortunate Mary Todd (Kay Hammond) is written as a self-absorbed shrew, and the villain Booth played by Ian Keith stops short of twirling imaginary mustachios but goes full steam ahead orating his lines with bulging eyes and clenched fists, all in heavy makeup which includes eyeliner. Huston himself has noticeable lipstick in some early scenes.

There are historical inaccuracies. The Lincoln-Douglas debates omit the subject of slavery altogether and focus on secession. In reality, the Union soldiers did not fire on Charleston, SC from Fort Sumter to start the Civil War, but the incident is portrayed as such though the reverse is true. The Secret Service delivers reports to Lincoln in the film, but it wasn’t established until after Lincoln’s death. And Lincoln delivers portions of his Gettysburg address at Ford’s theater just before he is killed – the entire Gettysburg speech completely missing from the film. And aside from the brief scene where he is showed signing the Emancipation Proclamation, the subject of ending slavery, Lincoln’s abiding obsession and his proudest accomplishment, is given short shrift. Griffith’s whole emphasis (and therefore his Lincoln’s) is on the subject of secession.

There is one shocking scene that shows Griffith’s lip service to the subject of slavery. While in the prologue there seem to be actual Black men portraying slaves, in a later scene a ‘good Negro’ is played by a white man in blackface telling white Southerners that he wanted no part of John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry and that he threw away the gun he was given.

But technically, there is much to admire in this movie given the context. The roving camera in the war scenes is especially effective, particularly in the post-Bull Run montage and the Battle Cry of Freedom sequence. Griffith pioneered the fade-out, the close-up, and the use of miniatures, though his use of one of the Lincoln Memorial in the last scenes of the movie is not quite successful.

In his biography, Griffith wrote about the eight-week shoot: “a nightmare of mind and nerves.” He resumed his drinking habit, and the picture was edited without his input. When he asked the studio for changes to the cut, he was refused.

The film is now in the public domain as the original copyright was never renewed and many versions of it are online, some missing the prologue. There is a card that precedes the restored version that says: “This restored edition of Abraham Lincoln incorporates all known existing footage of D.W. Griffith’s film. Portions of the soundtrack of the first three reels have not survived. During these sequences, dialogue and music cues are provided by subtitles.” The original film was in sepia-tone and ran 97 minutes. Several versions are now seen in black and white with the prologue missing entirely, for example, the one on Amazon Prime, but the one on YouTube has it.

The restoration of the film was done by The Museum of Modern Art with support from The Film Foundation, the Lillian Gish Trust for Film Preservation, and the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.