News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

Curtis Harrington was one of the few directors who began in the avant-garde and made the transition to feature narrative moviemaking. Like his friend Kenneth Anger, Harrington began by just picking up a camera and making movies, and both artists came out of the extremely particular world of the west coast art/poetry/cinema/music/occult world of the 40s and 50s. The last of Harrington’s non-narrative shorts, which had a life on the college 16mm circuit and in film societies, was The Wormwood Star (1956), a cinematic portrait of artist Marjorie Cameron, the widow of the rocket engineer and Aleister Crowley adept Jack Parsons. Cameron, who appeared with Harrington in Anger’s 1954 Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (along with Anaïs Nin and Anger himself), was called upon by Harrington to play the Water Witch in his first narrative film, Night Tide (1961, restored by the Academy with the help of The Film Foundation in 2007), about a sailor (Dennis Hopper) who falls in love with a boardwalk carnival performer (Linda Lawson) who he comes to realize is a real mermaid. I remember turning on a little black and white portable TV when I was young and being entranced by this homemade film, which seemed to emanate from its own planetary signal: related to a very particular strain of Hollywood cinema (under the sign of Josef Von Sternberg, on whose work Harrington had written a small book) but not quite of it, similar in spirit to the freshness of the French New Wave and Cassavetes’ Shadows but vastly different from both, Night Tide had its own trancelike, twilit magic. As was the case with so much in American cinema at the time, Roger Corman played a crucial role in getting Night Tide distributed.

Harrington went on to make many films in the very particular sub-genre spawned by the success of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? before he was drawn into what he called the vortex of episodic television. He was a key figure in American movies, a great raconteur and chronicler, and he worked and lived at the crossroads of multiple dynamic creative energies that exploded from the 50s through the 70s like a supernova. It still lights our way.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

Night Tide (1961, d. Curtis Harrington)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive with support from The Film Foundation and Curtis Harrington.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

“Cinema must be reinvented each time, and whoever ventures into cinema must also share in its reinvention.” I love this statement.

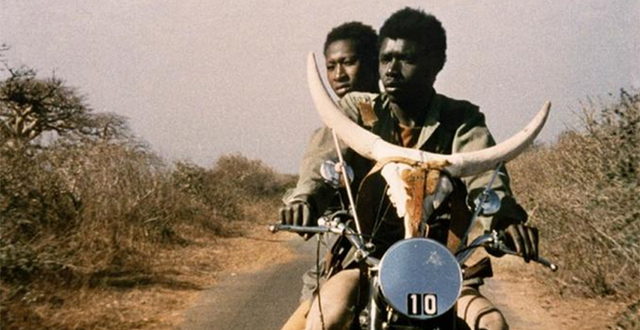

It was made in an interview by the Senegalese filmmaker Djibril Diop Mambéty. Consider the statement in relation to Mambéty’s own cinema and to his Touki Bouki in particular (the film was restored by the World Cinema Project in 2008). On first viewing, his classic 1973 film—about a young couple from Dakar trying to make their way to a supposedly better life in France—might seem unorthodox in the extreme and even disconcertingly fragmented. But like all real artists, Mambéty had no interest in creating work that would go down easily.

The tools for moviemaking are now more easily accessible and much cheaper than they were when Mambéty started. But that means many things. Here in the United States, we are in a period where lots of stuff gets commonly and carelessly labeled as “movies.” It is now lazily expected that absolutely everything will go down easily, that moviemaking will bend like a reed to the demands of every new political program or trend, that the past can be ignored because somebody else will pay attention to it. Moviemaking is now like the internet—“democratized” without any actual investment in or discussion of the idea of democratization. This is a laissez-faire attitude that often amounts to a resigned belief in the technology itself, which will presumably chart its own course, which harmonizes perfectly with the interests of every CEO everyone loves to hate. In moviemaking as it stands, pretty much everything is being thrown against the wall and almost nothing is sticking. And that’s because there’s a lack of investment in the very idea of cinema itself, which means an investment in its past as well as its present. It’s a state of affairs that can’t go on forever, and the way forward can only be a rediscovery of the cinema’s past, through new eyes.

Mambéty is now a part of that past. He died far too soon, in 1998 at the age of 53. It was extremely difficult to get a film made in Africa during Mambéty’s lifetime, and it still is. Like Rossellini and Godard and Cassavetes, he pulled back the curtain and showed the world that moviemaking didn’t have to be a daunting and wildly expensive endeavor made only by trained craftsmen and artists. It could be made in a spirit of freedom with minimal elements. But, it had to be made, with a commitment to the cinema itself. Otherwise, it’s just more content.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

TOUKI BOUKI (Senegal, 1973, d. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Restored in 2008 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the family of Djibril Diop Mambéty. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

There is a story told of the Baal Shem Tov, with which Elie Wiesel prefaced his novel The Gates of the Forest. Whenever there was trouble coming for the Jewish people, the great Rabbi would go to a particular part of the forest to meditate, light a fire, and say a special prayer that would avert looming disaster. After the Rabbi was gone, his disciple saw trouble coming again. He knew the place in the forest, he knew the prayer, but he’d forgotten how to light the fire, but his prayer was answered. Another interval of time, the disciple of the previous disciple, more trouble on the horizon: he’d forgotten the prayer, he didn’t know how to light the fire, but he knew the place in the forest, and disaster was again averted. And still later, his disciple saw looming disaster once again: he didn’t know how to light the fire, he didn’t know the prayer, and he didn’t know where the place in the forest was…but he knew the story. And that was enough to avert disaster once again.

I thought of this story when I was reflecting on the situation in which we now find ourselves with film exhibition. It’s a long, long road from the first Lumière screenings to where we are now, and there are many more generations and levels of forgetting than in the Baal Shem Tov story. The experience of going to the movies when I was young is to a millennial watching something—anything—on a streaming platform as the duck-billed platypus is to a plant-based sausage: you know that there’s some kind of relationship but you can’t articulate exactly what it is.

As cinema has been altered again and again by one business-driven decision after another, each of those decisions resulting in changes that have been deemed “inevitable,” every corner of cinema, from the quality of projection to the standards of film festivals to the level of discourse to the very idea of the art of cinema itself, has been affected by coarsening agents, and every new technological tool has been almost instantaneously packaged, sold and milked for every last penny. And as the years have gone by and the legal rights to film libraries have been passed from the control of one entity after another, each one governed by people further and further removed from any sense of cinema at all, the titles comprising those libraries have in turn been milked dry, and in turn “devalued,” to use Marty Scorsese’s term. Those of us who love the art form feel like followers of a faith seeing their sacred objects ransacked and sold for parts, like the young man in Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia who discovers that his family has been looting the sarcophagi in a nearby tomb and selling the treasures on the black market.

This post is not about any one of the many titles in whose restoration The Film Foundation played a part. It’s about all of them, each restoration undertaken with care and love, each one receiving the kind of attention that the very art of cinema now needs from those who love it. There is not “they” to automatically swoop in and protect it. When films are unavailable, we all have to cry out until they’re made available again. When they’re presented in substandard or compromised conditions, we have to hammer away at it until they’re presented correctly. When theatres shut down, we have to let everyone know that we want them to re-open and then to go back when they do. Now, we’re the ones who have to keep the cinema alive. We have to remember, every day, the place in the forest, the prayer, and how to light the fire. Because I’m not sure if the story will be enough.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

AL MOMIA (Egypt, 1969, d. Shadi Abdel Salam)

Restored in 2009 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, and the Egyptian Film Center. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways, Qatar Museum Authority and the Egyptian Ministry of Culture.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

When I got the news that Norman Lloyd had passed away at the age of 106, I called my friend Bruce Goldstein. Bruce and Norman had become close over the years, and they talked once a week on the phone. “How much longer can he go on, I wondered,” said Bruce. “But still, I’m very sad.”

I was sad because Norman lived through all of that history and was ready, willing and absolutely able to transmit it to the very end. I have a photo from eight years ago of Norman, 97 at the time, standing with my son Andrézj, who was 15. We were backstage at the Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard, where Norman was going to do an onstage conversation before a screening of Hitchcock’s Saboteur at the TCM Film Festival. In the photo, Norman looks like he’s in his 70s. And when he spoke, it was like listening to someone in their 60s. His answers were clear and concise, and he was as sharp as a razor. Here was a man who had no time for misty nostalgic wandering—he was still alive and there was too much to experience.

Norman Lloyd saw Babe Ruth play at Yankee Stadium. He acted with Eva Le Gallienne and Joseph Losey at the Theater of Action and the Federal Theater Project, which led to Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre Company, where he played Cinna the Poet in the company’s 1936 production of Julius Caesar in fascist dress. He was cast as Fry, the villainous saboteur in Saboteur, which began a long working relationship with Alfred Hitchcock, and it was Hitchcock who brought an end to Norman’s “gray list” period in the 50s when he hired him as an Associate Producer on Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Norman worked with Jean Renoir and for Chaplin, and became close friends with both. He produced the first staging of Brecht’s Galileo. He directed the lovely Mr. Lincoln for television and hired Stanley Kubrick to direct 2nd unit. He acted right up to the end, in television and in films.

One final word, about Saboteur, restored by the Library of Congress with help from The Film Foundation. I wrote a little about that film last November, around the time of Norman’s 106th birthday, and I find myself going back to it a lot. The film seems richer every time I look at it, and so does Norman’s performance as Fry, a great joint creation between director and actor: a quietly contemptuous Fifth Columnist who nonchalantly starts a blazing inferno in a California airplane factory, fights tooth and nail to sabotage a battleship in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, wolfishly responds to Priscilla Lane’s phony come-on at the top of the Statue of Liberty (I love his reading of the line, “Sounds cozy…”), and then elicits our sympathy as he hangs onto Robert Cummings hand and watches the stitches of his jacket pop one by one. What an amazing resourceful actor he was.

And what a life he led.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

SABOTEUR (1942, d. Alfred Hitchcock)

Preserved by the Library of Congress with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Foundation and The Film Foundation.