News

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

Back in the early 80s, I took a course in avant-garde cinema at NYU with the late Peter Wollen. We watched all of the films in the classroom, including Michael Snow’s 270-minute Rameau’s Nephew—I call attention to the running time because I remember Peter asking the projectionist to take a mid-afternoon break so that we could all get a quick bite to eat (we were undergrads, so that meant a slice and a Coke). Snow’s film was impressive but exhausting, and we all staggered up after it was over, only to cross paths with my favorite professor, Nöel Carroll, in the adjoining classroom. “Come on in and watch a real movie,” he said to Peter and those of us remaining, so I popped in and caught a few minutes of Roger Corman’s X – The Man with the X-Ray Eyes. Nöel’s passing remark wasn’t meant as a knock on Snow (he was an admirer of the avant-garde and wrote about it often) as much as an expression of excitement that he was showing a Roger Corman movie.

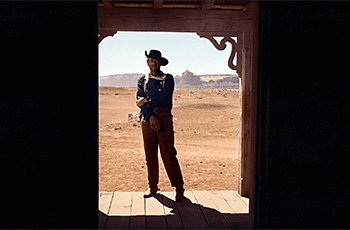

Roger Corman will be 96 in April. As a producer and a cultivator of young talent, he had a massive effect on the American cinema of the 60s and 70s. As a distributor, he imported Bergman, Truffaut, Rosi, Schlondorff, Herzog, Kurosawa and Fellini. And as a director he made a torrent of films between 1955 and 1971 (he returned to directing to make one more film in 1981, Frankenstein Unbound) that did as much to re-orient and re-invent the idea of cinema and the role of the filmmaker as the work of Mekas, Warhol or Godard. He is best known as a director for a cycle of Poe adaptations, almost all of them starring Vincent Price, that he inaugurated in 1960. The series ended with two relatively lavish 1964 pictures shot in England, The Tomb of Ligeia and The Masque of the Red Death. Corman put off making the latter film, adapted from a story set in the time of plague in medieval Italy, for several years because he wanted to avoid comparisons to The Seventh Seal. The film is often noted as his greatest visual achievement as a director (it was shot by Nicolas Roeg), and it has been beautifully restored by the Academy with the support of The Film Foundation and the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. But for me Corman’s work is all of a piece, a torrent of films made for low budgets on tight schedules with little if any fuss, as elemental as the first silents, grounded in a real love of the work of making films. I treasure the spirit of those films. It’s no wonder he launched so much talent.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u_mHJ1pyZEU

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=147iz2lO2kI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijAw7tOljEA

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZxDRWuaHplM

THE MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH (1964, d. Roger Corman)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

A few years back, The Film Foundation and the Academy Film Archive, with support from the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation, started working on a restoration of Lewis Milestone’s 1931 film version of Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s 1928 play The Front Page, produced by Howard Hughes. The restoration team was confronted with an all-too-familiar situation: the original negative was gone. In the case of this particular film, three original negatives were gone: Milestone’s preferred American version, the UK version and the international version. The invaluable Michael Sragow documents the history behind the restoration, which was based on a print of the American version struck from the original negative in the 1970s, in his excellent notes on the film for the Criterion edition of Howard Hawks’ His Girl Friday, which includes the Milestone film as an extra.

The Front Page has been a mainstay of American culture since Jed Harris’ original 1928 Broadway production (directed by George S. Kaufman), which starred Lee Tracy and Osgood Perkins (father of Anthony). It has been regularly revived on the stage, most recently by Jerry Zaks in 2017, with John Slattery and Nathan Lane. I remember taking my grandmother to see a 1986 Lincoln Center revival with Richard Thomas and John Lithgow (that cast also included Julie Hagerty and my pal Deirdre O’Connell). There are four film versions, the most famous of which is now the Hawks film (the 1988 Ted Kotcheff film Switching Channels, which changed the milieu from print to cable TV journalism, is actually more of a His Girl Friday remake). Why does The Front Page resonate?

Because it portrays journalism as a profit-driven exercise in sensation-seeking, for which reporting the truth is a secondary consideration; because the sensationalism is easily found in the world of power-mongering big city politics; because it’s hilarious when it’s done right and brilliantly plotted. At a moment when sensationalism is now common currency in the press, from the smallest smalltown gazette to the Old Gray Lady herself, when doom is ever-impending and “likely” cataclysms are lurking around every corner, when Tweets are treated as news and time frame stretches as far back as five minutes ago and ahead as far as tomorrow…yes, I’d say that The Front Page does indeed resonate, particularly in this glorious restoration. To quote Sragow, it’s “the zestiest and most influential movie you’ve never seen.”

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/4382-the-front-page-stop-the-presses

https://www.film-foundation.org/the-front-page

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cpFqjTSki1Y

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Szhv93Ppon0

THE FRONT PAGE (1931, d. Lewis Milestone)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation. Elements for this restoration provided by The Howard Hughes Corporation and by the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, College of Fine Arts' Department of Film and its Howard Hughes Collection at the Academy Film Archive.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

It’s astonishing to go back and revisit the films that Orson Welles made in Hollywood, and to realize just how far he was from that world. John Ford’s simple, lucid observation about Jean Renoir—“He’s not one of us”—applies equally to Welles. The majority of the many great films that came out of the studio system were dances with the many rules and restrictions imposed by the Production Code, as well as the unwritten but tacitly understood rules that resulted in a general squeamishness about the roles of money and spirituality in people’s lives, as well as an anxiety about maintaining a sufficiently high standard of presentation: nothing could look too untended. Regarding the question of money… I can think of many well-documented reasons for the butchering of The Magnificent Ambersons, but one of them is the film’s absolute frankness about the predatory downside of “progress.” The same can be said for The Lady from Shanghai, whose collection of avaricious monsters resembles a school of bloodthirsty sharks, as Welles’ character observes in one of the film’s greatest scenes.

Welles’ stark, hallucinatory Macbeth, shot at Republic Studios on bargain basement sets with barely functional costuming, was his most “abnormal” Hollywood film (made right after his most “normal,” The Stranger). He made it in 23 days for $200,000, standard conditions for B-moviemaking. Within the context of the business itself, this was interpreted as a “demotion,” and Macbeth would be Welles’ last Hollywood film until Touch of Evil a decade later.

Apart from the minimal sets and props and advance rehearsal time, how was Welles able to make his film on such a schedule? It’s easy to think of many reasons.

- He had staged the play before, in Harlem in 1936, with an all-black cast under the banner of the Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. "By all odds my great success in my life was that play," Welles said in 1982. "When the play ended there were so many curtain calls that finally they left the curtain open, and the audience came up on the stage to congratulate the actors. And that was magical.”

- He knew Shakespeare inside and out.

- He worked with actors who knew their way around Shakespeare, including the formidable Jeanette Nolan as Lady Macbeth, the Irish actor Dan O’Herlihy (making his American film debut) as Macduff, and Mercury Theater members Edgar Barrier as Banquo and William Alland (the reporter in Citizen Kane) as one of the murderers. (Also in the cast: Welles’ daughter Christopher as Macduff’s child, and Jerry Farber, nephew of the film critic Manny Farber, as Fleance.)

- He had the actors pre-record their dialogue, a practice that he had planned for The Magnificent Ambersons and then quickly abandoned.

- The pre-recording and the rehearsing led to the employment of extraordinarily lengthy and fluid takes shot from a crane, planned and executed by Welles with a great DP, John L. Russell. One of those takes runs the length of an entire ten-minute reel.

- The most important reason of all: Orson Welles was a genius.

As it happened with every Welles film made in Hollywood apart from the first and most famous, Macbeth was artistically violated in the name of money-driven panic. It was cut (of course) and the cast’s voices were re-recorded without their original thick Scottish brogues. In 1980, UCLA’s Bob Gitt found a dupe negative of the complete version, which had been shown in Europe, and some fine-grain master elements, and he did the first photochemical restoration. In 2006, The Film Foundation provided Gitt with the funds for another round of restoration that made use of digital technology. It’s interesting to take a look at the Welles in light of Joel Coen’s new version. But then, whatever the pretext, it’s always a good idea to revisit an Orson Welles movie. See above, Reason 6.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2oQPJfabpPI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb10g9BD9ZI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJ6v7GHYDbM

MACBETH (1948, d. Orson Welles)

Preserved by UCLA Film & Television Archive in cooperation with Paramount Pictures with funding provided by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association and The Film Foundation.

NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

The first time I met Peter Bogdanovich, it was in his Upper West Side apartment in the late 90s. I interviewed him for a story I was writing for Cahiers du Cinéma. He was gracious, quiet, and thoughtful. I remember that we sat across from each other by a little table with a lamp on it, and we discussed the plight of the movie director as the art of cinema had developed over time. The context was the Politique des auteurs and how it had metamorphosed into the auteur theory on these shores, which resulted in a school of film criticism on the one hand and, in a sense, the New Hollywood on the other. Peter brought up the familiar question of influence. “I personally knew all those directors who influenced me,” he said, “and I always gave them credit, because by the time I knew them they weren’t able to find work. It was a good will gesture, but I was also genuinely inspired by them. And then they all died.”

Many of those names appear often on The Film Foundation’s list of restored titles. They were among the greatest artists in the history of movies. Peter programmed one of the first major retrospectives of Howard Hawks’ work in the early 60s. He did oral histories of Fritz Lang and Allan Dwan, and John Ford, whose presence haunted Peter’s films. He also made a beautiful documentary about him in the early 70s, released not so long before Ford’s death, and then he went back and expanded and enlarged it 35 years later. His greatest and most complicated friendship was with Orson Welles. The last time I saw Peter was at The New York Film Festival in 2018, when he came for The Other Side of the Wind. For years, he had been involved in getting that film—which had taken up an enormous amount of his own time and energy for decades, on a variety of fronts—into finished form. His performance is the emotional linchpin. It had been a few years since I’d seen him last and he seemed markedly frail, but he spoke with great, sad eloquence.

I won’t pretend that I knew Peter well. We just crossed paths from time to time in the cinema universe. But whenever we did, it was warm and convivial. I could see the burdens he carried: like his old friends, he needed to find work. As a young man, he was brashness personified, and I still remember how astonished I was to see him filling in for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. With The Last Picture Show followed by What’s Up Doc followed by Paper Moon, he became one of the world’s most successful directors. With Daisy Miller (the first of his movies that I saw, and I still think it’s one of his best) followed by At Long Last Love followed by Nickelodeon, he got his “comeuppance,” to quote The Magnificent Ambersons. With the murder of Dorothy Stratten, his whole life was shattered. He did what everyone does: he went on. It seemed to me that he bore it all with great grace and acceptance.

I have to say that I was shocked by his death. Because he was so respectful of those directors he loved, so willing to celebrate them and remember them whenever the occasion arose, he always seemed young.

Now, the eternal son is gone. And he’s the one whose memory must be kept alive.

- Kent Jones

Follow us on Instagram, and Twitter!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7yCQ_ko28IQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQPzzNhqGCo

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OnPJxu2TgW8