NOTES ON FILM & RESTORATION

01/13/2021When I was the director of the New York Film Festival, I got used to hearing the same question posed annually. One year, it was phrased like this: “You’ve been accused of running an ‘auteurist’ festival. How do you feel about that?” My answer was always the same: “If you mean do we show films made by human beings who create individual artistic responses to the world around them, then I plead guilty as charged.” The question was never meant maliciously, but in that spirit of obligatory equanimity that is a fixture of modern journalism. But lingering behind the question is the familiar spirit, always with us in ever-mutating forms, of condescension to art.

This condescension is even present in the stated attitudes of cultural institutions that resort to high-flown rhetoric as justification for their existence—art can “enlighten” us and “touch the soul” and “enrich our lives,” all of which is so vaguely obvious as to be beside the point, and incidental to what art is and does.

Art will always be fragile, no matter what the political or cultural climate. It will always be called upon to financially justify itself, to demonstrate its “relevance,” to prove its adherence to this or that social doctrine or movement no matter how worthy, and it will always be open to charges of “elitism” from those opportunistic enough to make them.

At a moment like this one—today, January 13, 2021, in the United States of America—art will be seen as beside the point. In terms of the immediate and pressing reality, that’s obviously the case. But art lingers as a powerful, looming presence in the background of all moments of upheaval, and, I would wager, in the lives of many people who are now engaged in debate on the floor of the House of Representatives.

“St. Thomas Aquinas says that art does not require rectitude of the appetite, that it is wholly concerned with the good of that which is made,” wrote Flannery O’Connor. “He says that a work of art is a good in itself, and this is a truth that the modern world has largely forgotten. We are not content to stay within our limitations and make something that is simply a good in and by itself. Now we want to make something that will have some utilitarian value.” But the utilitarian value of an individual novel or painting or film is always incidental and has a short expiration period. When it’s at its most powerful, it doesn’t confirm or rebut or prove or disprove or condemn or celebrate anything. It takes on a life of its own and poses a cosmic, unanswerable question. It sees, it reveals itself before us, and it makes us shiver.

Over the years, Martin Scorsese and Margaret Bodde and Jennifer Ahn and the members of The Film Foundation’s board have been asked multiple variations on the question “Is film restoration necessary?” The question is always posed in the same spirit that I mentioned above. And it’s always best answered with another question: if you recognize the value of cinema, then how could film restoration not be necessary?

The cinema doesn’t put food on the table. It doesn’t provide for the common defense or keep the trains running on time or resolve territorial disputes. To paraphrase Daniel Berrigan, it is useless in the sense that God is useless, because neither are part of the kingdom of necessity.

The Film Foundation has participated in, facilitated and commissioned the restorations of so many films. Here are some images from a few of the most fragile.

THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR (India, 1960, d. Ritwik Ghatak)

Restored by the Criterion Collection in partnership with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the Cineteca di Bologna, from elements preserved by the National Film Archive of India.

THE COLOR OF POMEGRANATES (Armenia, 1969, d. Sergei Parajanov)

Restored by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory and The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, in association with the National Cinema Centre of Armenia and Gosfilmofond of Russia. Restoration funded by the Material World Charitable Foundation.

LOST LOST LOST (1976, d. Jonas Mekas)

Preserved by Anthology Film Archives through the Avant-Garde Masters program funded by The Film Foundation and administered by the National Film Preservation Foundation.

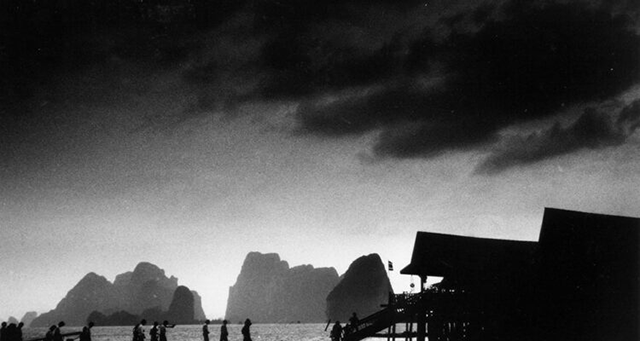

MYSTERIOUS OBJECT AT NOON (Thailand, 2000, d. Apichatpong Weerasethakul)

Restored in 2013 by the Austrian Film Museum and Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, LISTO laboratory in Vienna, Technicolor Ltd in Bangkok, and Apichatpong Weerasethakul. Restoration funded by Doha Film Institute.

TOUKI BOUKI (Senegal, 1973, d. Djibril Diop Mambéty)

Restored in 2008 by Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory, in association with The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the family of Djibril Diop Mambéty. Restoration funded by Armani, Cartier, Qatar Airways and Qatar Museum Authority.

VOICE IN THE WIND (1944, d. Arthur Ripley)

Restored by UCLA Film & Television Archive and The Film Foundation, in collaboration with Cohen Film Collection. Restoration funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.

THE WAY TO SHADOW GARDEN (1954, d. Stan Brakhage)

Restored by the Academy Film Archive and The Film Foundation, with funding provided by the Hobson/Lucas Family Foundation.